The last few times GCC pegged currencies like the Saudi Arabian Riyal (SAR) were this dislocated, they were ‘saved’ by a reversal in oil prices or the US$ (or both). Time will tell if history repeats itself. One thing is for sure though – the current environment is not a great cocktail for the SAR/$ peg (or any of the other GCC pegs for that matter).

Proponents for keeping the peg will rant off the same templated rationale we’ve been hearing for years: 1) Saudi really only exports one thing – US$-priced & hydrocarbon-derived energy (whether in the form of oil or oil/associated gas-by-products like petrochemicals and fertilizers) while importing everything else under the sun from cars to industrial parts to migrant labor, to food & water (through protein). This narrative argues that a devaluation really will not help the balance of payments in the short run. And 2) The pegs have served the GCC countries well in the past as they have created visibility and stability for local and foreign investors alike- but especially for foreign direct investment which is a key objective for the success of the Saudi 2030 vision (Saudi needs all kinds of foreign capital, not just financial, but more so intellectual). We believe both assertions are mere rationalizations (at best) and distractions from what really matters (at worst).

Goldman Sachs last week came out unsurprisingly (they were one of the lead bankers to the PIF on the Aramco IPO) as a cheerleader of the status quo, saying that the US$ peg “has been of significant benefit to the Saudi economy over the years”, and that “unlike a devaluation, fiscal policy can shift the burden of adjustment on those more capable of bearing it through, for example, taxes on luxury goods”. Goldman’s report goes on to say that “this is not to say there would be no economic or sociopolitical costs [of a purely fiscal adjustment], but we believe these would be lower than in the case of a devaluation.” Even the IMF recently chimed in saying that Dollar pegs in the Gulf have been “serving [the GCC] very well, and [are] still appropriate, especially countries who have buffers that have the ability to use their reserves in order to address the shock.”

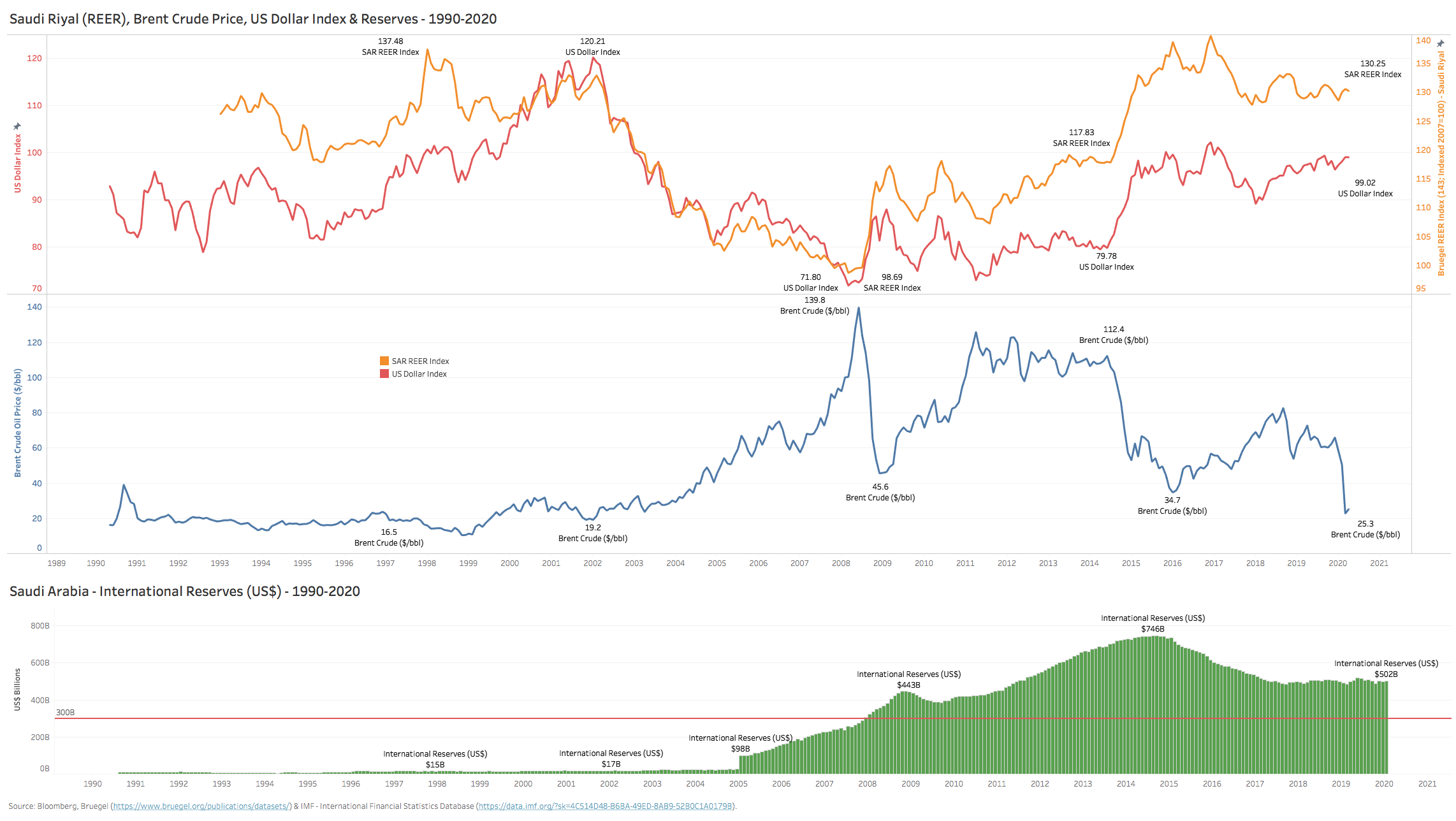

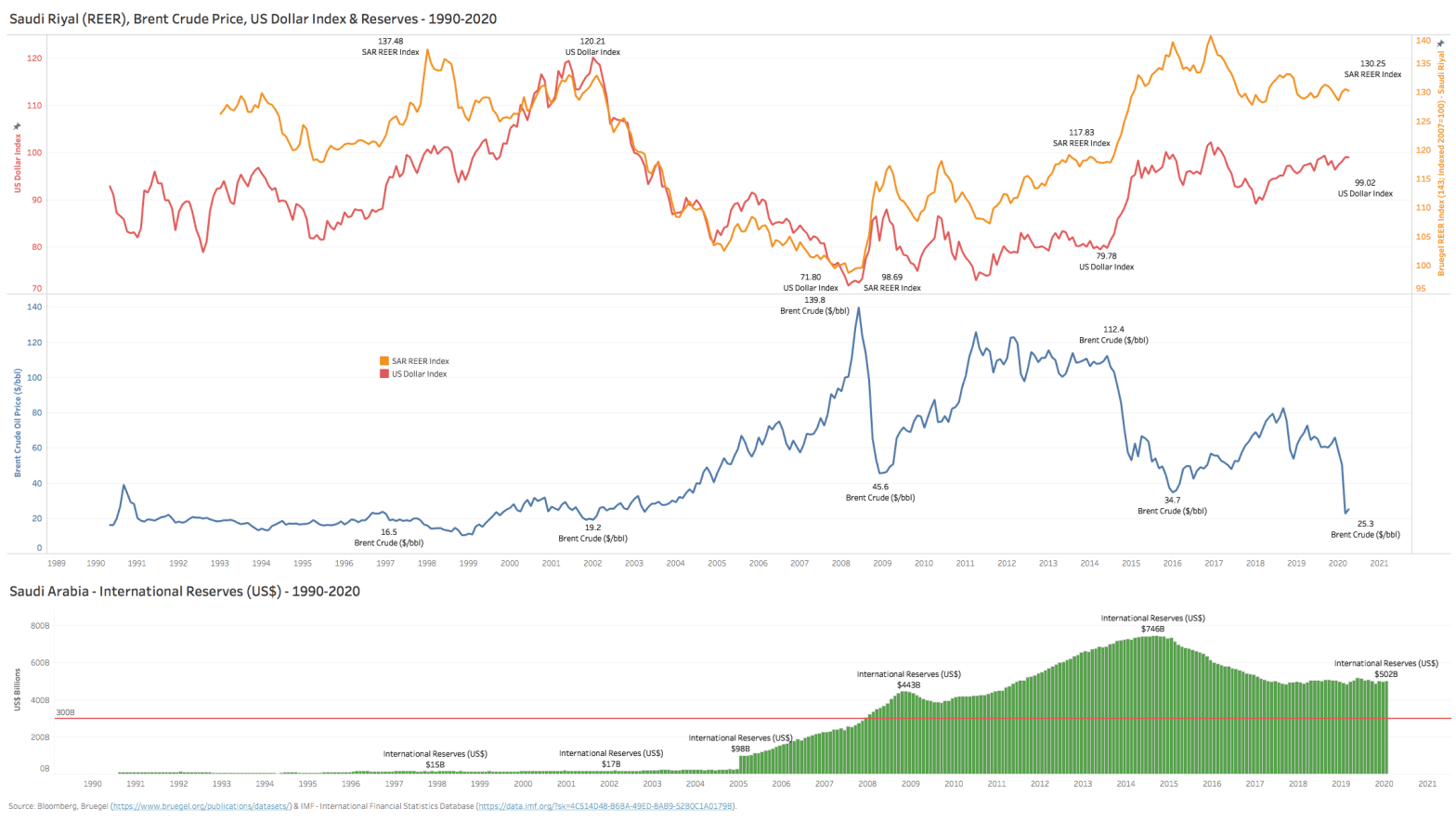

However, what both of these esteemed organizations gloss over is the key element of competitiveness and the ability and incentive for rapid diversification that a dollar peg inevitably kills. By stubbornly tethering the value of the SAR to an ever appreciating US dollar, the Saudi currency is forced to appreciate in real terms (see the REER Index below in Chart 1 which puts the SAR at at least 30% rich vs. fair value) and as a result, renders the currency even less competitive to its regional and global peers who maintain some form of currency independence from the USD and thus are able to adopt counter-cyclical policies.

The peg also creates a very tight straight-jacket on the Kingdom in terms of policy flexibility. Consider the options any country with a pegged currency has to adjust to a big fiscal and balance of payments shock that may also face borrowing constraints at some point in the future: a) lower deficits by cutting spending and/or increasing current revenues – mainly through current taxation, b) borrow more debt to fund the deficits (effectively an increase in future taxation) or c) inflate away your existing debt (which is in effect taxing your past savings).

Option c) is effectively off the table since since the $-peg anchors you blindly to US monetary policy and inflation. Tightening the fiscal side (a) is precisely the wrong type of policy during an external shock like a pandemic, since in order to stimulate growth, a country like KSA needs to adopt aggressive stimulative policies (higher spending/lower taxes) in order to allow growth to recover. If you are constrained in expanding your fiscal revenue base, you are left only with option (b) as an exit valve, which means your sovereign gearing will increase at a very accelerated pace as you fund rigid and increasing deficits.

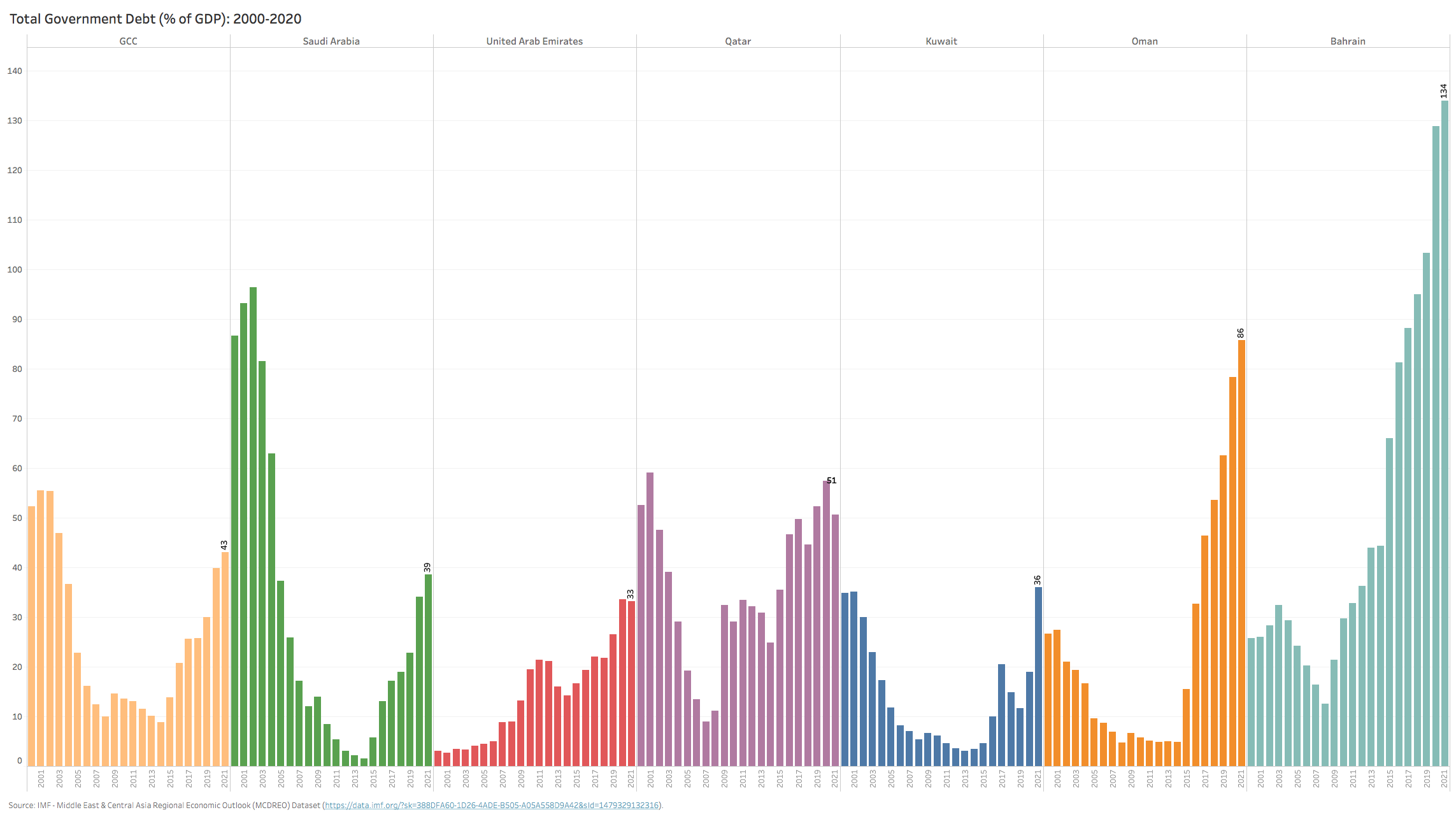

Today, Saudi showed its policy hand by announcing a tripling in the VAT (from 5% to 15%), cutting public sector cost of living allowances and reversing large employment & salary increases (for both public and private sectors) while also unilaterally cutting oil production. The cut in production is somewhat ironic since it is an about-face after the disastrous oil price war with Russia that began just two months ago yielded little in terms of net revenue gains. With a relatively inflexible public sector wage bill, a very low tax contribution to the fiscus and lower oil revenues, these steps are unlikely to yield enough savings to really move the needle in suppressing high debt stock accumulation. So, what is more likely to occur is the classic ‘two steps back’ (debt accumulation in a low growth environment that will likely persist as the economy’s capacity shrinks and a drawdown in reserves ensues) and ‘one step forward’ (small savings from ill-timed fiscal austerity).

This all begs the bigger question: why should the Kingdom continue to abdicate its sovereignty over monetary policy and exchange rate flexibility and competitiveness, just to protect the peg? Who/what does the peg really serve most? Is the peg really sacrosanct because of the potential impact it may have as a regressive tax on KSA’s citizens or is it really protecting the wealthy classes who benefit most from the status quo? In more ways than one, a cheaper currency may in fact allow the country to level the playing field as to resource allocation, shifting more resources and investment away from hydrocarbons.

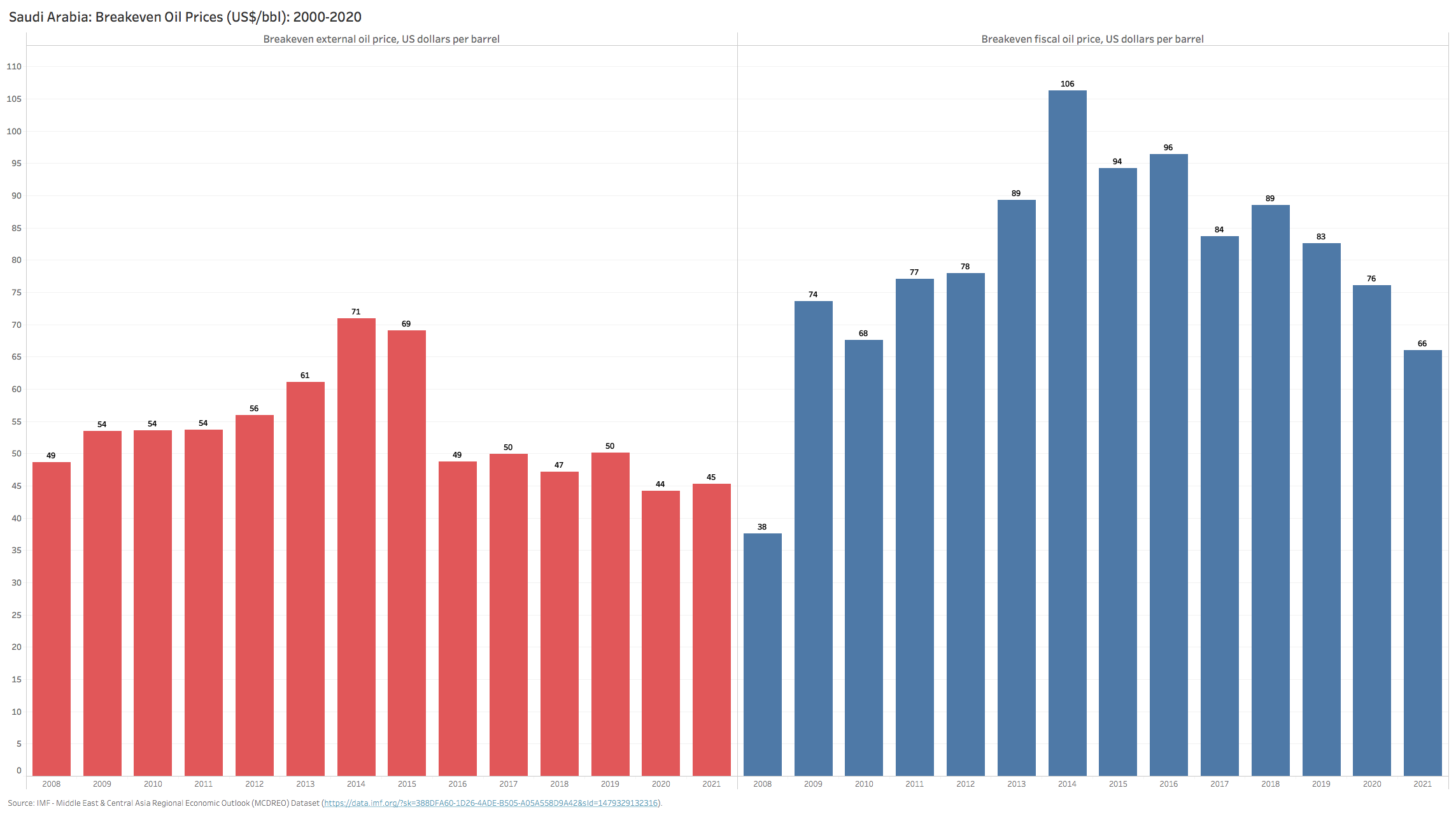

Imagine what a more competitive SAR could produce for the Kingdom: 1) a much needed boost for non-hydrocarbon-linked industrial exports & services and high value added or R&D intensive technology which are currently not competitive, especially vs. regional peers like Egypt or Morocco who both have far more competitive currencies, and 2) a much needed lever to inflate local SAR debt, depreciate SAR spending & operating expenses, thereby materially lowering the Kingdom’s overall fiscal break-even level for oil exports (akin to what Russia did successfully in 2016). Evidence from the last two decades of policy inaction is that the status quo has failed miserably in diversifying away from extreme oil-dependence (see the level and trend in non-oil revenues and non-oil deficits below in Charts 6 & 7) – both expected to deteriorate markedly in 2020/21 by the IMF as they have proven to be much more inter-linked with the oil economy (via government spending) than most would admit.

In the meantime, and assuming the persistence of the peg, how much will Saudi Arabia and the rest of the GCC central banks spend (and waste) from their precious reserves and offshore savings to defend pegs that serve no real tangible purpose other than to maintain a regime that no longer serves any real economic purpose? The folks at Goldman estimate that Saudi Arabia has some room in terms of existing reserves to maneuver and point to a $300 billion minimum threshold in net reserves to cover the monetary base. But should this reactionary and defensive calculus really be the right sustainable policy direction for the Kingdom?

If Saudi Arabia were a company, would it be wise to allow the balance sheet to deteriorate at such a fast pace through reserve depletion (arguably the main source of anti-fragility) and massive debt accumulation (a future tax on the next generation) just to protect a peg that has lost all its efficacy (assuming it ever had any)?

We are all proponents for the structural reduction in the fixed cost base (KSA is amongst the world’s top spenders on arms/military as a share of GDP, high and overly generous public sector wage spending, costly and distortive energy/water subsidies, huge ‘white elephant’ projects), but should not these measures also be accompanied by higher spending on productive and essential human capital categories (education, healthcare) or productivity-enhancing infrastructure? A depreciation of the SAR at this juncture would provide the Kingdom with much needed fiscal space and the flexibility to more aggressively reallocate their fixed cost structure. It would also go a long way in relieving the pressure on reserves at a time when capital is dear. Why is this not a policy option that is legitimately on the table? We have yet to hear a compelling reason.

If oil prices do remain low for the foreseeable future (next 2-3 years), these kinds of voluntary options may disappear from KSA’s toolkit, especially as the forces of negative operating leverage accelerate (revenues from hydrocarbons falling precipitously, while fiscal costs remain stubbornly fixed). This in turn can lead to an accelerated drop in cash flows and a ballooning of debt – both at a much faster pace than most expect.

Why postpone the hard decisions to when your options are more limited and your hand may be forced?

Note to Readers: For a better viewing of charts, please right click the chart image and open as a new window to view in full resolution.