Note to Readers: For a better viewing of charts, please right click the chart image and open as a new window to view in full resolution.

“Iraq reminds me of a classic Shakespearean tragedy – whenever you think things just can’t get any worse, the plot surprises you by taking yet another major step down.”

George Soros (2007)

“When I assumed responsibility, I found an almost empty treasury and an unenviable situation after 17 years of change. Our sovereignty continued to be deficient, violated and doubted. The past period did not see any [effort to] upgrade vital sectors as industry, investment, food self-sufficiency and others. The current crisis [affects] all state institutions and aspects of Iraq’s development and economic revival.”

Prime Minister Mustafa Al-Kadhimi (Baghdad Today, May 2020)

“To recognize the presence of genuine political action in the Arab spring is to reject a narrative of nihilism in favor of a call to political responsibility. It is time to recognize that the future of the Arabic-speaking world is and ought to be made by the people who live there, not from the outside. Their successes and failures will be, and must be, their own.”

Noah Feldman, The Arab Winter – A Tragedy (2020)

Introduction

The first quote above was delivered to me and my partner at the end of a long conversation with George Soros in the Spring of 2007 (he was then Chairman & CIO of the Quantum Fund) on the subject of Iraq & Syria. We had just returned from a trip to the region and briefed Soros on our findings and overall impressions. One of George’s more admirable and impressive qualities is his willingness and sincere interest to listen to alternative points of view. He did so with the patience and humility that few with his stature, experience and wisdom tend to have.

After completing our debriefing on both countries, Soros gave us his frank assessment for Iraq (the quote above was his poetic endnote). In the vein of most Shakespearean tragedies, George saw the flaws and grave errors of what was at the time a new Iraq – emerging from nearly three decades of wars, sanctions, ethnic/sectarian conflicts and insurgencies. Soros was not only a vocal critic of the Bush administration’s decision to invade Iraq in 2003, but remained deeply skeptical of the political, social and economic structures the country inherited from its American liberators and which the Iraqis adopted thereafter.

In retrospect, George’s snap assessment of Iraq proved prescient. In the decade that followed 2007, Iraq, its economy and the Iraqi people faced innumerable obstacles, disappointments and challenges, some of which proved later to be existential in nature. Iraq’s newly appointed prime minister, Mustafa Al-Khadhimi’s public proclamation to a local newspaper (the second quote above), given during the early weeks of his premiership in May this year, aptly summarizes Iraq’s depressing yet pragmatic report card for the past 17 years – undoubtedly the prognosis of a failed state.

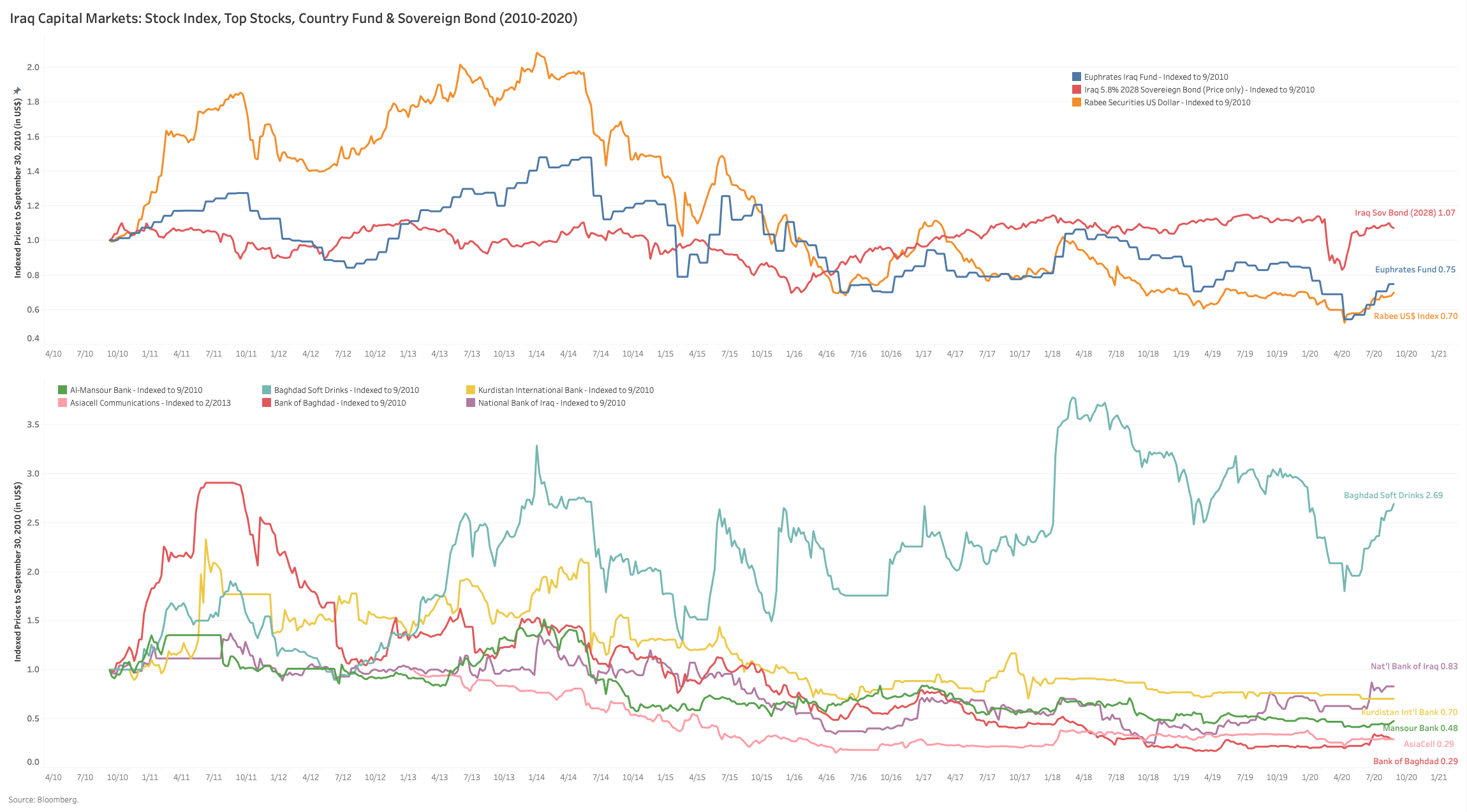

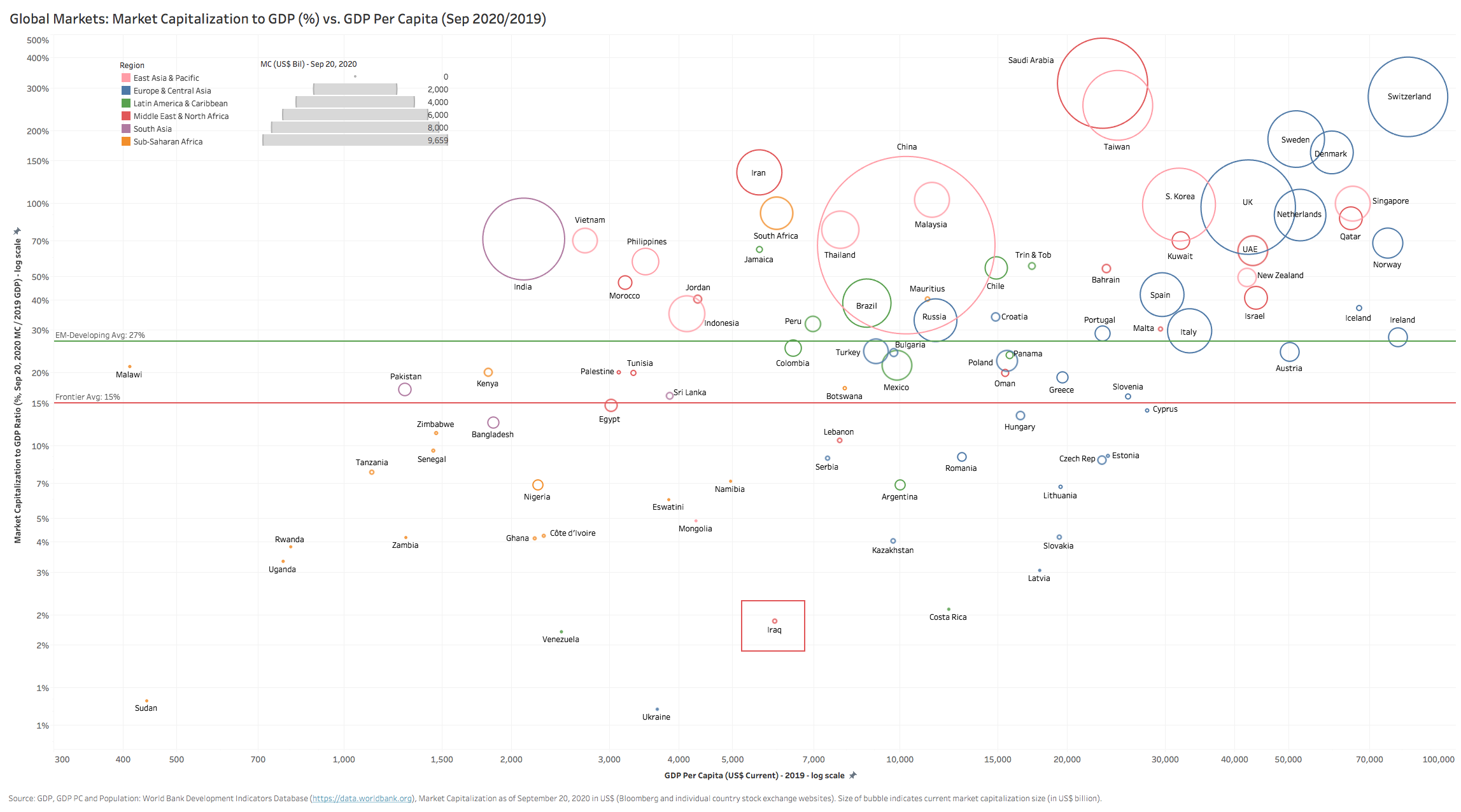

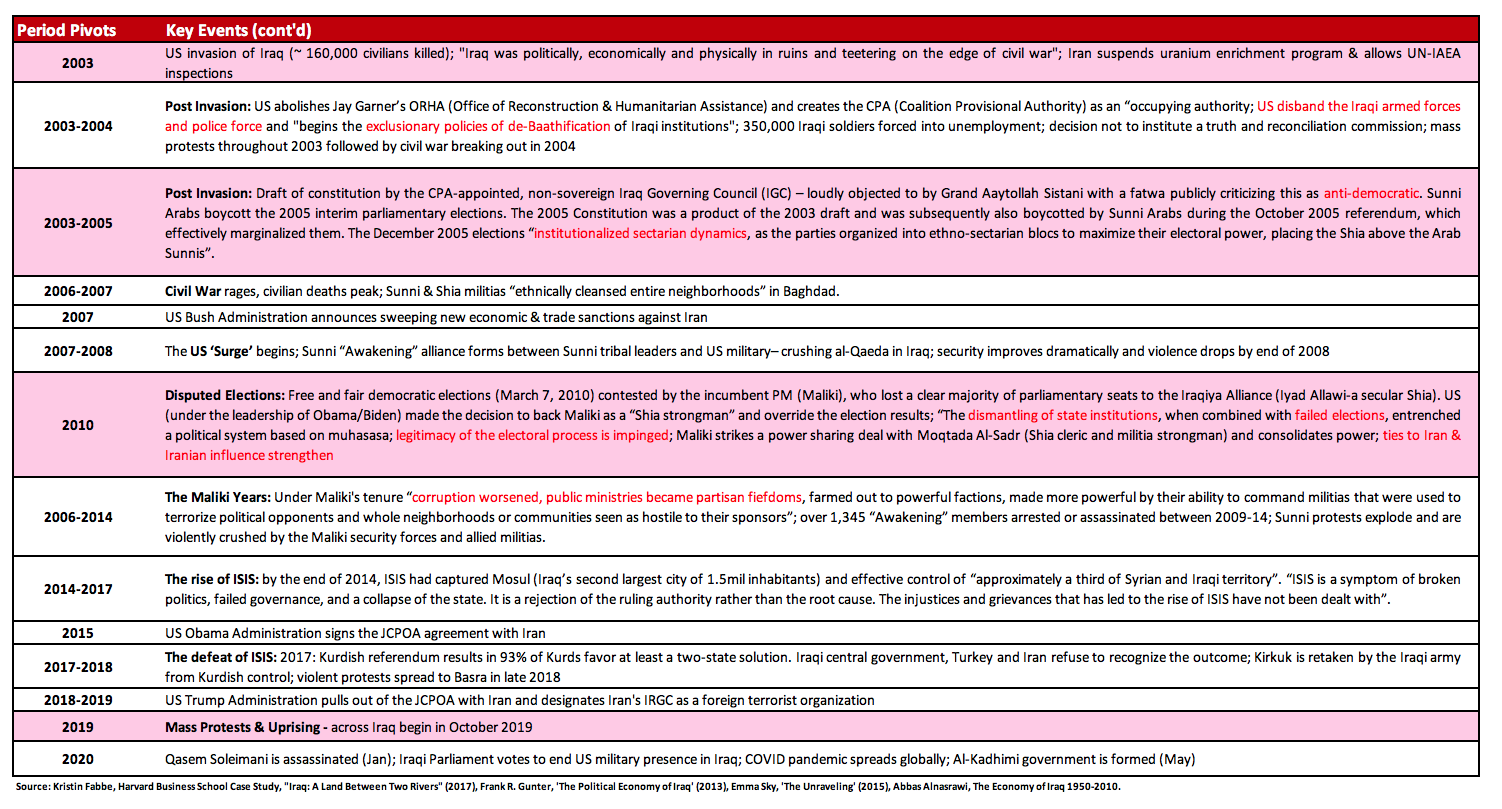

We won’t rehash Iraq’s troubling recent political history since far too many pundits have done so over the years at great length. If you want to see a snapshot of key milestone events from Iraq’s early history to the present day, please refer to Table 1 in the Appendix and Charts 1 & 2 later on in the note (the latter super-imposes trends on Iraq’s per capita income and oil production). Iraq may be an outlier in terms of the degree of tragedy it has experienced and the duration of its struggles, but one cannot argue that the country’s experience over the past few decades is a big departure from those of the region it is located in. Even though the Iraqi historical arc’s amplitude may be greater than that of its neighbors, the general trend is unfortunately quite similar across the Arab World at large.

As a result, we believe that it may be particularly useful at this juncture in Iraq’s punishing history to also take a step back and look at the country squarely in the context of the Arab World, especially around the period of the Arab spring protests and the aftermath of the 2011 uprisings. Iraq remains a very complex puzzle, though we find that sometimes by looking through a specific conceptual lens (like that of the Arab spring’s post-mortem) one can potentially clarify and simplify what is otherwise a very noisy picture.

The new wave of protests across the region that began in 2019 and extended well into 2020 in Algeria, Sudan, Lebanon and Iraq seem very familiar to us as onlookers. The first Arab spring, when it began to spread in 2011, from Tunisia to Egypt, and eventually engulfing most Arab states, left several countries relatively unscathed. The likes of Lebanon and Iraq did not fully participate in this first wave of uprisings, primarily because their uniquely sectarian political systems created a formidable distraction for the deeply divided masses. These sectarian cleavages made it easy for an individual party to deflect blame onto the other.

Fast forward to 2019 and the overall environment has deteriorated to such an extent in these countries that it is impossible for any individual party in the ruling class to hide from responsibility. The people across Iraq and Lebanon have taken to the streets accusing all politicians for having failed them, inclusive of their partisan overlords. With one voice they are now loudly rejecting the sectarian system that the status quo rests on, unifying under a banner of nationalism and reform while calling on a complete overhaul of the system of governance. Déjà vu?

But this time at least feels different. Iraq has experienced its largest mass protests since 2003-4, a period of huge distress that followed the US invasion and a wholesale change in regime. Iraqis of all stripes are now loudly claiming that the sectarian system that was put in place post-2003 is not workable. The muhassassa (a pluralistic-intended system based on rigid sectarian quotas) has only yielded an outcome of institutionalized favoritism based on sect and ethnicity, allowing political parties to effectively divvy up the oil wealth between them by turning ministries into sectarian fiefdoms. According to experts such as Emma Sky (a Yale lecturer, former advisor to the US-CPA and author of several important books on Iraq), the country has devolved into a kleptocracy in short order.

Many western observers of the Arab World dismissed the consequences of the first Arab spring protest movements (or uprisings) of 2011 as either abject failures or meaningless experiences that have either led to chaos, tyranny, terror or (at best) a fragile stability derived from a reprofiling of the old autocratic political structure. We believe that this prognosis is not only simplistic but also quite premature. This is especially the case if one considers that the uprisings in 2011 were in fact only the first phase of a longer-term transition, driven at its core by a powerful assertion of self-determination. We firmly subscribe to this view and believe that the first Arab spring was in fact a generational watershed moment for most Arab countries, a collective awakening of sorts and a potent catalyst for what is likely to be a lengthy process of transformation rather than a finite and conclusive event in itself.

The final quote above from Noah Feldman’s 2020 book – The Arab Winter encapsulates this intellectual framework where he labels the second phase of this transition process as an ‘Arab winter’. According to Feldman, the 2011 uprisings signaled “a new, unprecedented phase in Arab political experience, in which participants engaged in collective action for self-determination that was not conceived primarily in relation to imperial power”. Arab protesters exercised something quite rare for the countries of the region – “political agency” and a “courageous pursuit of a more just political order.” Whether they did so as a result of the failure and subsequent weakening of external influences (US, GCC, Iran, Russia, Turkey) or whether the Arab streets advocated a more democratic model in the transition (or a rejection of a democratic result as in the singular case of Egypt) – these are questions that can and have been debated. The key take-away for us from the original Arab spring was that the experiment with self-determination in fact succeeded in engendering change. Whether this change can be transformational is yet to be determined.

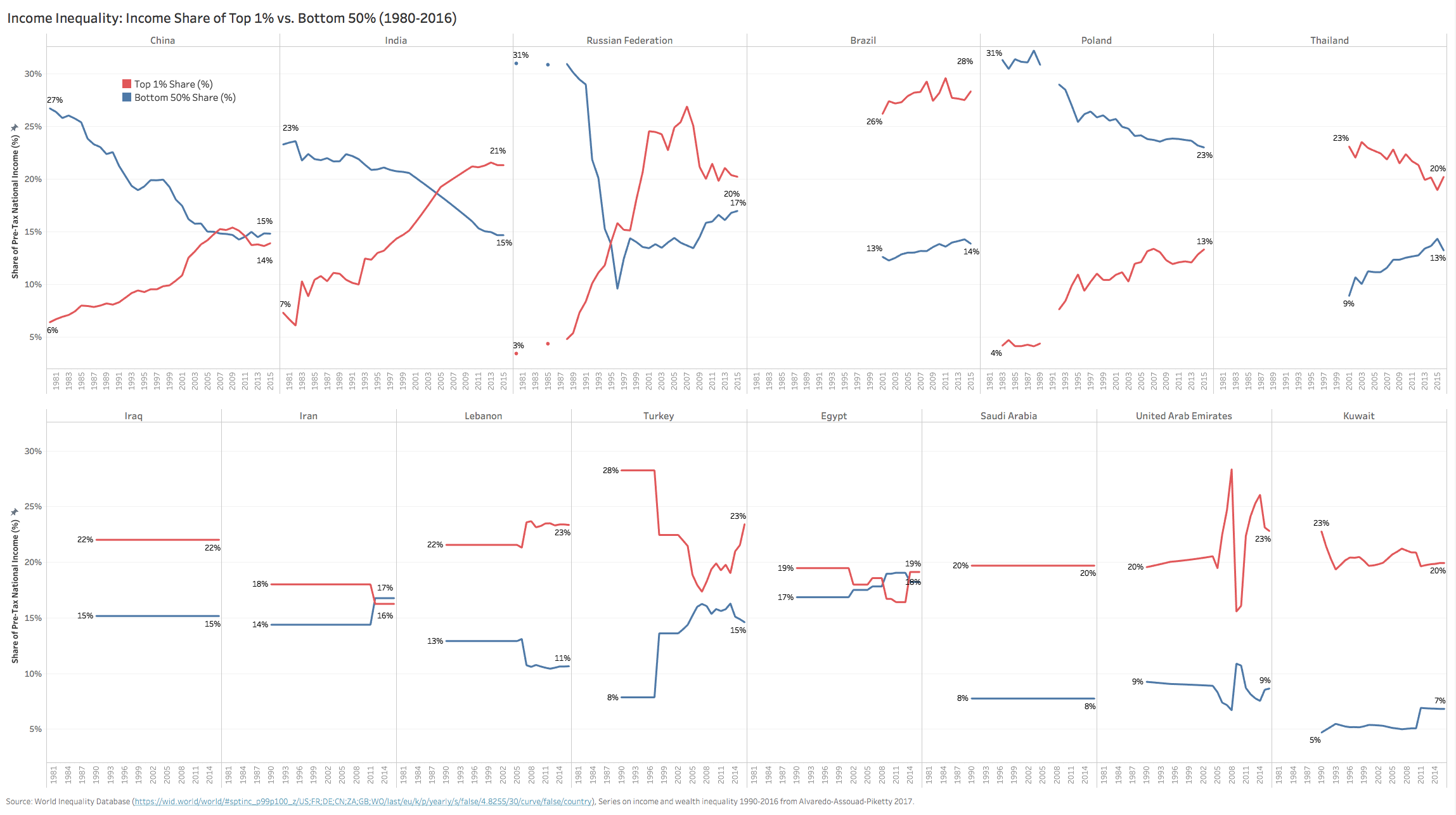

Across the Arab World however, in almost all cases of upheaval thus far (arguably with the lone exception of Tunisia), the tragedy of “inconsequential change” persists well into this second phase, while in some cases the tragedy in fact has intensified through repression of civil society, rising levels of inequality (income- and gender-based in particular), an erosion of living standards, higher levels of physical displacement (internally-displaced or refugees), internal civil strife, and in some cases even armed conflict.

However, because the claim of self-determination is now established in most countries, it is far less likely to be muffled indefinitely. Pandora’s box is now open and only the countries that can afford to effectively bribe their citizens into passive submission for extended periods (e.g. some of the smaller Gulf States with huge hydrocarbon resources per capita) will be able to temper this claim indefinitely. Subsequent uprisings are therefore inevitable, especially since the new status quo has failed to address protesters’ claims for social justice, more representative governance and more equal access to economic opportunity. The water in the metaphorical pot will remain very hot unless the heat is structurally removed, with the inevitable risk of boiling over as long as the status quo persists.

So far, one of the key deficiencies for any successful country transition has been the absence of a credible alternative political option to the incumbent autocratic governments – one that can deliver on security, opportunity as well as freedom (of all forms, including political, religious, civil and expression). The experiment with political Islam as a chosen form of governance has resoundingly failed in this respect, with contrasting post Arab spring experiences in Egypt (the rigid and exclusionary Muslim Brotherhood) and Tunisia (the progressive and accommodating Ennahda) both reaching similar failed outcomes, albeit with varying degrees.

Nevertheless, autocracies for the most part not only continue to come up short in addressing key issues of social justice, economic inclusion and sustainable growth, but have protected their hold on power by reinforcing the influence of vested interests and crony capitalists that are appendages of the ruling regimes. Therefore, we believe that subsequent uprisings are inevitable and may eventually come at a time where a transition to an alternative form of governance grows more likely. Legacy autocratic regimes are progressively becoming weaker and more vulnerable due to failing social and economic models, while credible alternative leadership (many from younger generations) eventually evolves and finally emerges onto the political stage. This will likely be a slow and drawn out process, with very different paths and outcomes for each country, but one that is worth watching closely.

So where is Iraq in this context of post-Arab spring evolution?

The US’s mishandling of the occupation (2003-10), beginning with the disastrous US decision to dissolve the army and police force, delayed the devolution of power and a return of security. As a result, this stunted the process of rebuilding a proper and sustainable institutional bedrock for the country. Furthermore, Iraq’s chosen political model (the 2005 constitution and the first series of parliamentary elections) was quite exclusionary, alienating the large Sunni Arab minority. This decision laid the ground for years of civil strife and eventually the spread of ISIS into Iraq from Syria, creating an existential threat to the federal state. Fast forward to 2020, and with several years of relative autonomy, a semblance of security, and with some inklings of democratic institutions having been formed, Iraqis of all stripes are now able to collectively claim their self-determination more assertively and across partisan lines. They have done so as a reaction to a disastrous governance track record and the absence of an occupying force like the US to direct blame towards.

But Iraq is not alone in this current phase of upheavals. Just as we witnessed in the 2011 Arab spring uprisings, the wave of discontent has begun to spread once again to the weakest links across the Arab World. Since the spring of 2019, in addition to Iraq, governments in Algeria, Sudan and Lebanon have been brought down by mass protests with chants and slogans that are eerily similar to those we heard almost a decade ago. With the precipitous fall in oil prices that followed the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020, we have also begun to see huge economic and social vulnerabilities emerge in both hydrocarbon-exporting countries and importing countries alike due to ill-equipped economic models, inadequate health infrastructure and weak social safety nets. Unlike the period following the Global Financial Crisis (2008-9) where global liquidity and rebounding oil prices were enough to soften the impact of local recessions (‘bribe the masses and hope for submission’), the current environment is fraught with record-setting deficits, extended sovereign balance sheets and even less inclusive and more repressive political structures.

As investors, a key question we are challenged to address at this juncture is: How close are these countries to reaching what Feldman calls the point of Catharsis[1], which he describes as the “inevitable culmination of most tragedies”? According to Aristotle, the Greek word “catharsis” is a “purging or a purgation; an inner experience that transcends the emotions of terror and pity and turns them into something cleansing.” Feldman also offers up Ibn Rushd’s nuanced, Arabic-lens interpretation for a tragic catharsis which takes the concept of catharsis further and considers the reaction to a tragedy as “not [merely a] reflection, but the doing of politics as the highest form of human flourishing.” Feldman explains that “the point of tragedy, in this vision, is to offer inspiration for the exercise of virtue. Tragedy can thus be made to have a practical, forward-looking purpose. It can lead us to do better.” We interpret this as the point where extreme adversity for a country finally leads to bold action – an inflection point towards the noble pursuit of transformational reforms in governance.

When will any of the Arab states reach this critical inflection point? Is it also possible that some countries never reach this cathartic stage, instead they muddle along indefinitely through an endless cycle of tragic outcomes? Every country obviously has very different circumstances and conditions, different resources to draw upon, varying demographic constraints, differing touchpoints, external influencers and (most importantly) thresholds for collective pain & suffering. At the conclusion of his book, Feldman summarily predicts that the “current winter may last a generation or more” and thus conveniently relieves himself from the challenge of predicting this important pivot. As an investor, we don’t have this intellectual luxury.

Is Iraq now at the point of maximum pain and thus able to turn its tragic catharsis into actions that are constructive, noble and virtuous? Is Iraq ready to finally turn the corner and begin a new and exciting transformation that will offer the young generation of Iraqis a brighter future? Are the necessary ingredients now in place for such a transition to occur: security, rule of law, basic institutional fabric and the emergence of a new political class that is ready to govern inclusively?

It is difficult to predict this. Instead, in this note, we have chosen to take a contrarian perspective, and ask a far less popular, yet a deliberately contingent question instead: what might Iraq look like in 10 years if in fact the country is successful in pursuing a real transformation? If the new Iraqi leadership decides to take a ‘noble’ governance path instead of the path of least resistance, what might the future look like and what implications will this have on Iraq’s potential economic growth, the country’s sovereign risk profile and ultimately the country’s investable asset classes?

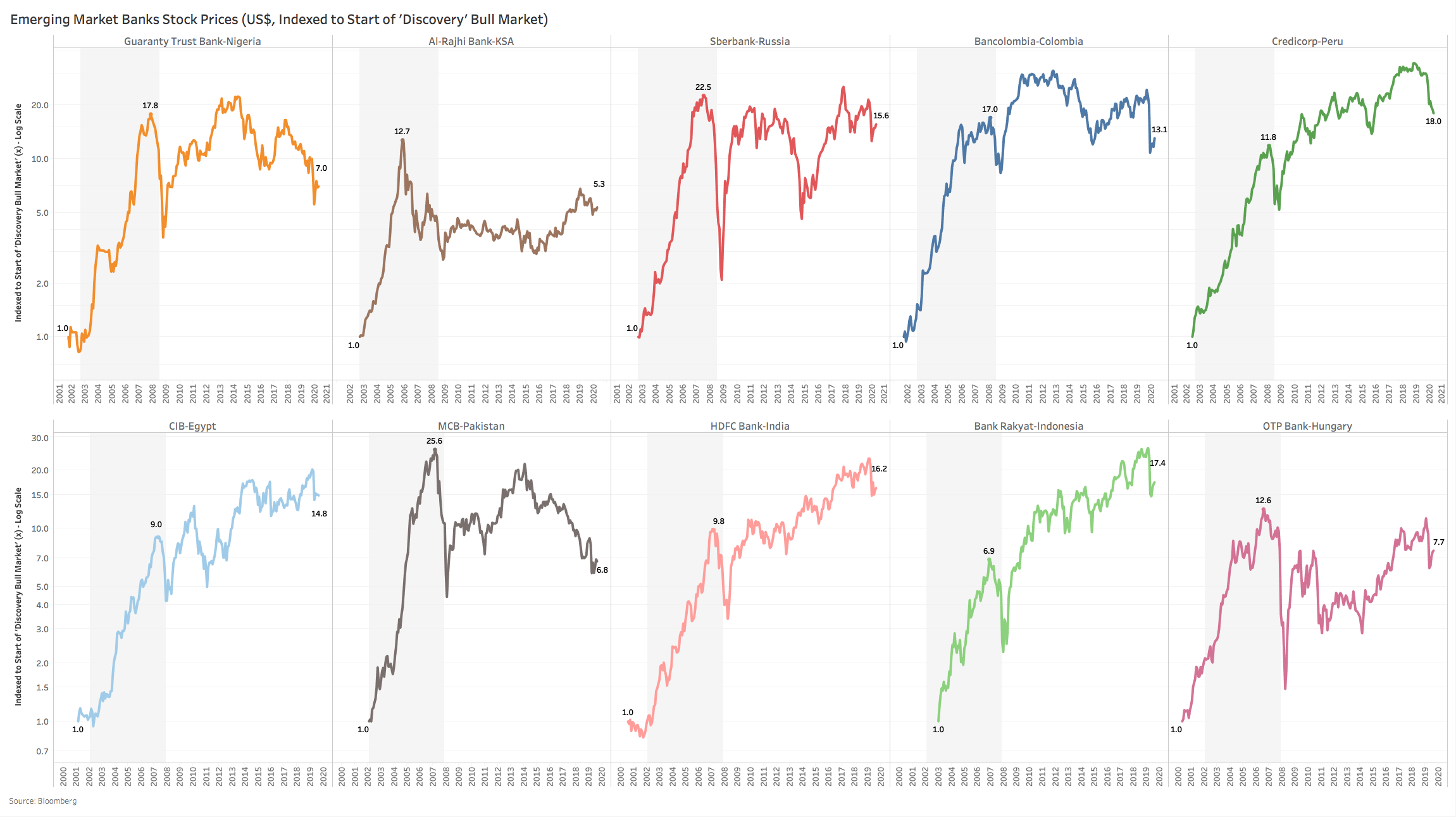

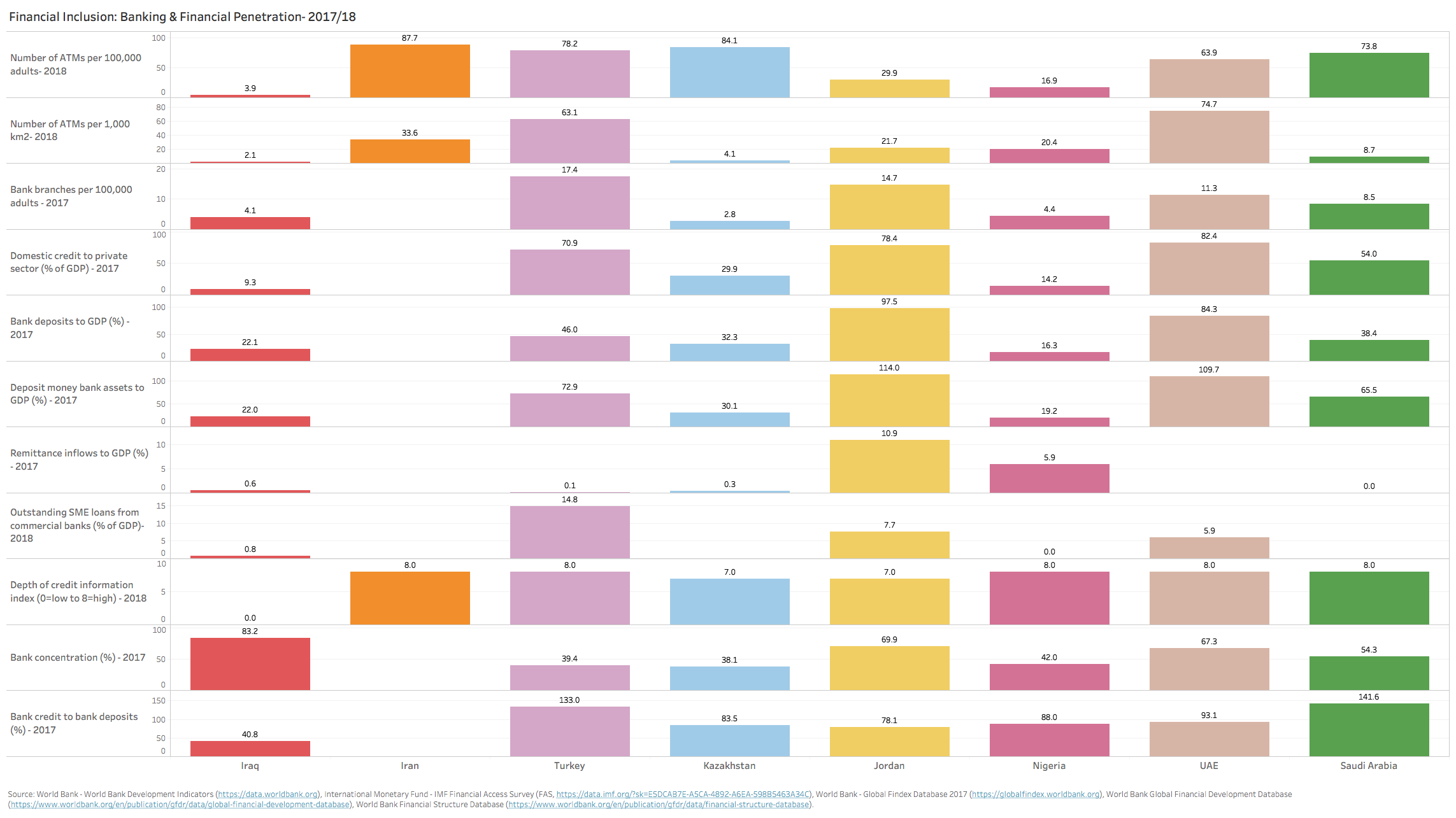

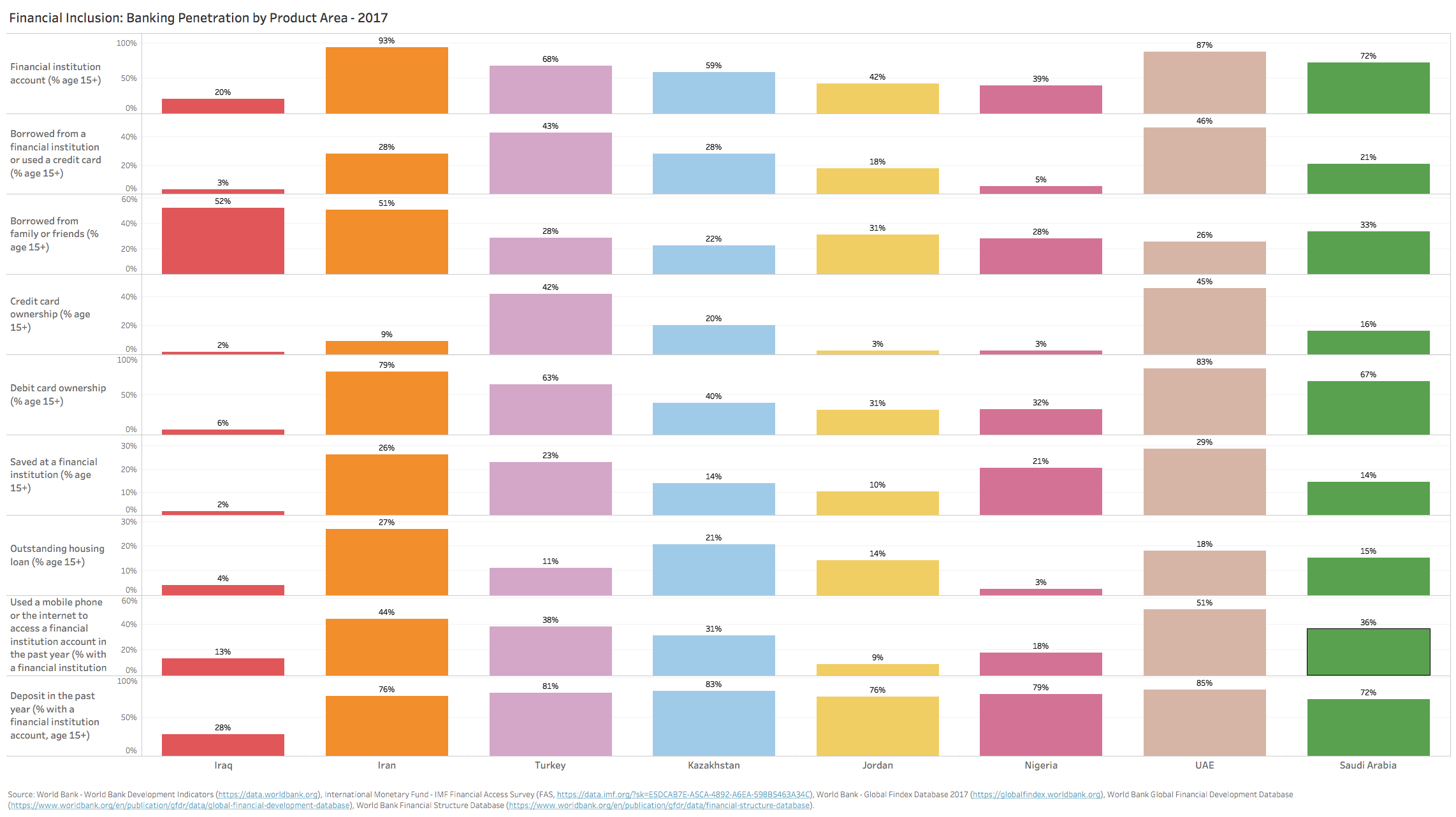

We will first draw out the current historical picture a bit further, explaining our views of the political and economic context for transition, highlighting both the positive aspects that reinforce the potential for successful reforms taking hold as well as the formidable obstacles that they face. We will conclude with a fresh look at Iraq’s nascent banking ecosystem and capital markets, which is always a great perspective into a country’s real economy and its potential for normalized growth.

A few notes for our chosen format of analysis. We love data and we love charts that illustrate and amplify the information contained in the data. Each chart or table paints a picture and each picture is in turn a small piece of a bigger puzzle that helps to flesh out a particular narrative. We have tried to be as objective and as thorough as possible in our analysis of the data, and therefore we use a lot of charts! Since most of the charts are packed with lots of granular data, we also chose breadth over conciseness. Charts that speak directly to specific analysis are contained in the main body of the note while those in the Appendix are there mainly for reference. Readers are recommended to open each of the charts in a separate window (right click and open in a separate browser page or download into a picture file) in order to view the entirety of the chart in full resolution.

POLITICAL TRANSITION

As with many fragile and post-conflict developing countries, most of the analysis on Iraq tends to be myopic, incredibly reactionary and overly retrospective in nature. As a result, and because Iraq’s historical coverage is so extensive, any evaluation invariably gets bogged down in so much historical noise. Testament to this is the typical view of Iraq’s modern history by most historians and economists. Abbas Alnasrawi, a noted economic historical scholar, encapsulates this common image best in his book ‘The Economy of Iraq: Oil, Wars, Destruction of Development Prospects’: “the country’s political history can be rewritten as an endless series of coups and countercoups; conspiracies; purges and counter-purges; violent seizures of power; ruthless suppression of dissent; and wars, adventures, and sanctions. In all this history, the people had no voice -there has been a virtual absence of democratic institutions and political parties.” But that cannot be the whole story or only what one takes away from such a tragic series of events.

Nevertheless, the full arc of Iraq’s history is fundamental to understand how the country has evolved and where its political, social and economic profile stands presently. What we do find particularly useful though is to zoom out of the noise and look at key pivots in Iraq’s history – the events that have real gravity, the big turning points and key decisions that, in perfect hindsight, proved to have altered the direction of policy and reforms in a material manner.

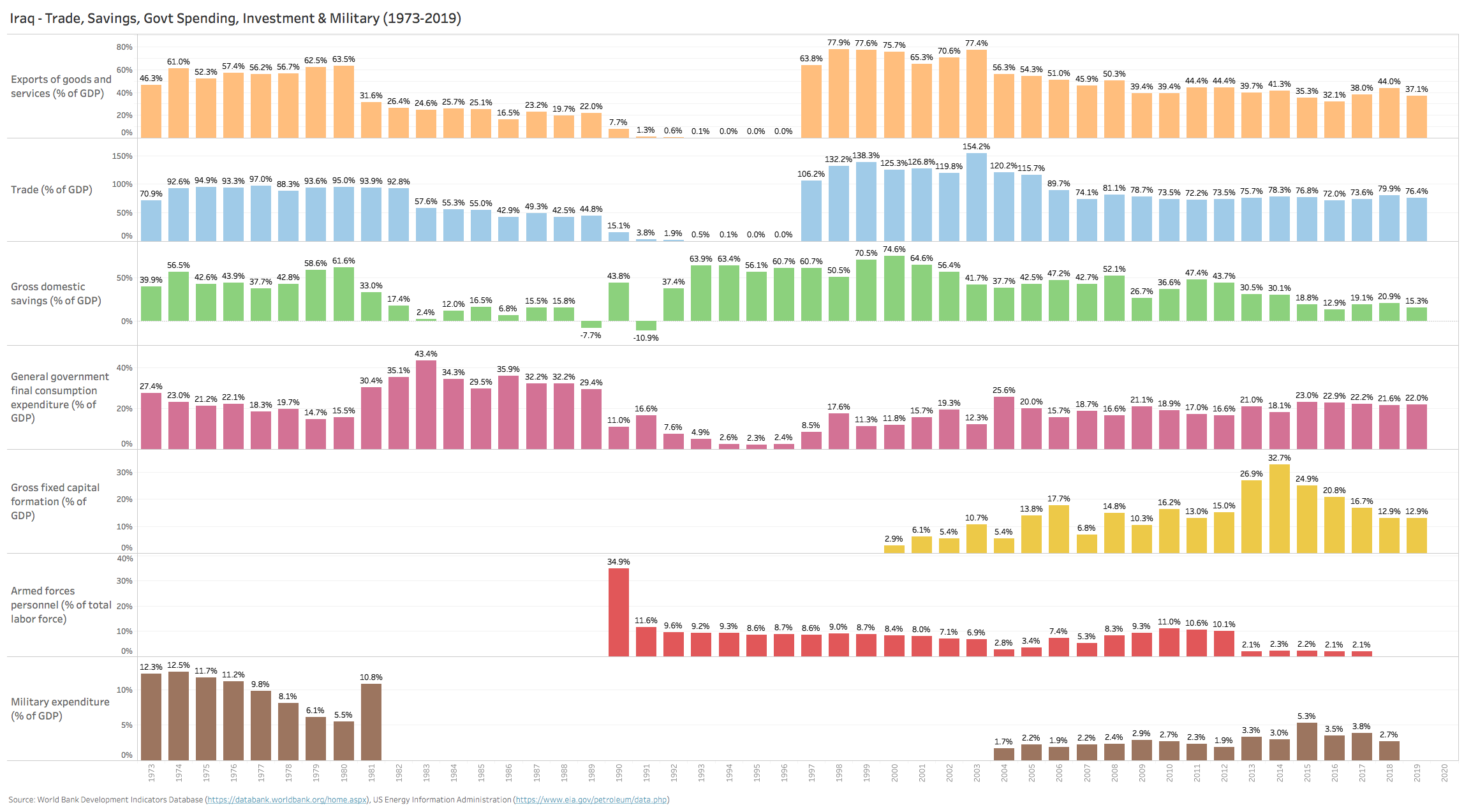

Unsurprisingly there are quite a few of these important pivots for a country with such a volatile history as Iraq. Table 1 in the Appendix is just a short summary list of some of the most prominent turning points that we lifted primarily from a superbly written country case study published by Professor Kristin Fabbe of the Harvard Business School in 2017 titled ‘Iraq: A Land Between Two Rivers’ (2017) (emphasis/highlights in the table are ours). Because our perspective is tinted mainly with an economic/investment lens, we will weave in several of these pivotal periods and milestones in the economic transition section of the note below. Charts 1 & 2 below also super-impose trends in Iraq’s oil production, oil exports, per capita income, per capita household spending and per capita oil export revenue onto the historical timeline for the reader’s reference. While the pre-2003 trends are not at all surprising, the post-2003 trends are especially noteworthy, despite (or as a result of) the incredible amount of event ‘noise’ during the early stages of Iraq’s post war transition.

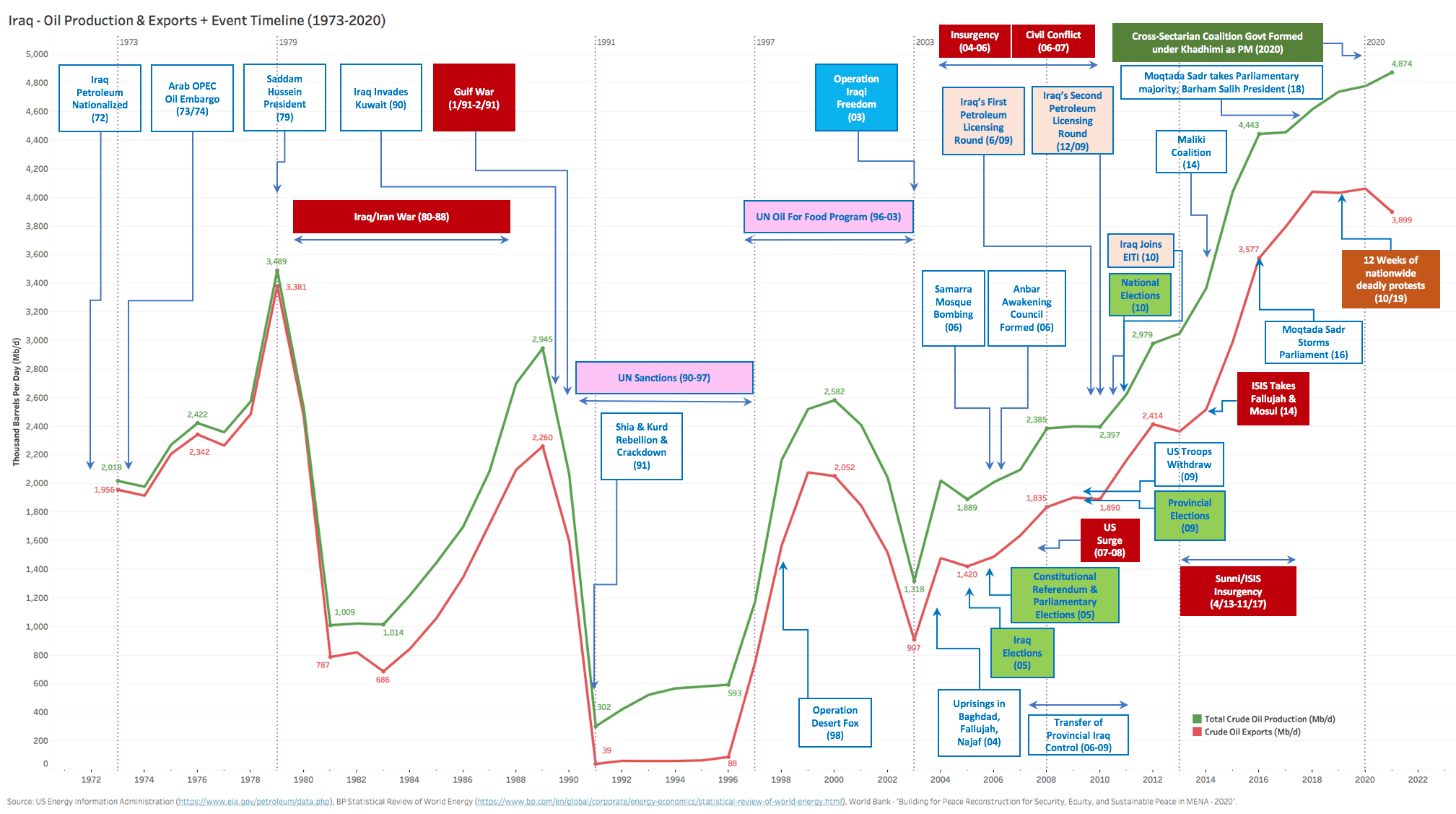

Chart 1 – Iraq Oil Production & Exports + Event Timeline (1973-2020)

Chart 2 – Iraq Per Capita (GDP, Household Spending & Oil Export Revenue) – 1973-2020

Beyond the obvious key milestones of: 1) the 1973 nationalization of the oil sector (arguably the beginning of Iraq’s ‘rentier’ stage), 2) the 1979 Iranian revolution which shook the bi-polar balance of power of the region and acted as a catalyst for the Iran-Iraq war and 3) the 2003 US invasion of Iraq, two more recent events are also worth highlighting here since we believe that they have had a disproportionate impact on where Iraq now finds itself today: A) the exclusionary drafting of Iraq’s 2005 constitution and B) the highly controversial outcome of the March 2010 election with a resulting blow to the legitimacy of the electoral process and perceived fairness of governance (see Chart 3 below for a summary of the 2005-2018 election results). We believe that these two more recent events also go to the heart of what needs to change politically in order for Iraq to chart a more sustainable path forward.

Chart 3 – Iraqi Election Results: March 2010 & December 2005

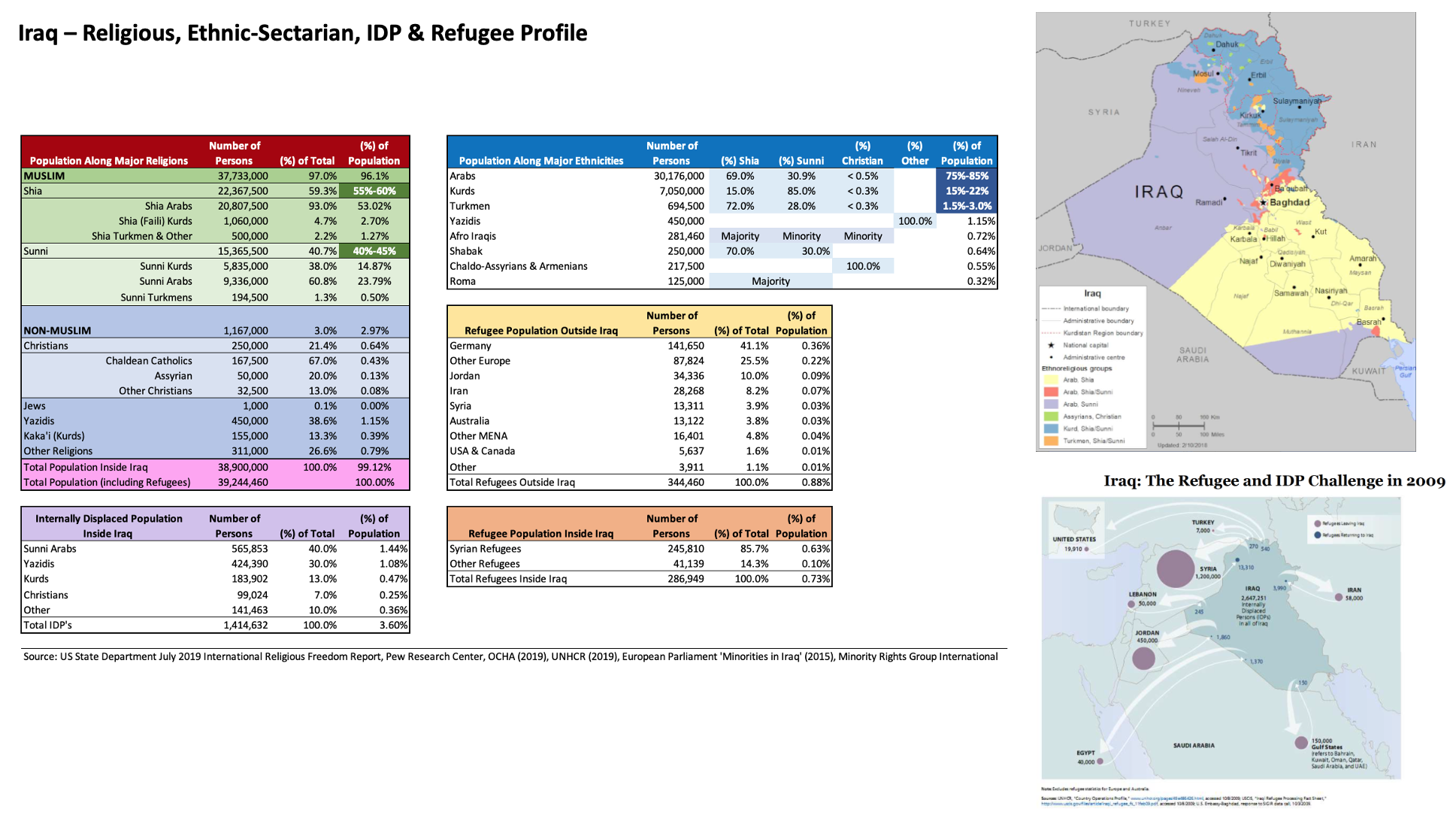

It is also no coincidence that both events were driven by an exclusionary ethno-sectarian policy that has entrenched itself in the Iraqi political system to date, with prospective implications for a dramatic drop in voter turnout and a fracturing of political parties and alliances across partisan lines. Nothing illustrates this more clearly than a contrasting look at Iraq’s current ethnic and religious profile (see Chart 4 below pieced together from several sources; many figures are our own guestimates since a detailed and credible ethnic/religious census is not available). This profile is a virtual kaleidoscope of underlying cultures and belief-structures that literally crisscross one another from a centuries-old brew. Iraq is much more than just Shia-Sunni or Arab-Kurd. The country stands apart from most of its Arab peers in terms of its sheer diversity and the thousands of years of history it has in cultivating this high level of diversity. This is precisely what Iraq’s 2005 constitution and inclusive electoral system were supposed to protect and promote. The 2010 election unfortunately ended up contradicting all of this.

Chart 4 – Iraq’s Religious, Ethno-Sectarian, IDP and Refugee Profile 2019/2020

This wrong turn in the road ultimately needs to be reversed and a more inclusive and representative government needs to emerge from prospective elections that are free and fair, without external meddling. Can this happen? Is the institution of Iraq’s young and pluralistic electoral system still intact, or has it been permanently impinged? Equally, can the rushed and misconceived Iraqi constitution be amended whilst protecting its legitimacy without risking the collapse of the federal state? Time will tell, but these are a few of the key catalysts that we will watch closely as we approach the coming June 2021 parliamentary election cycle and its aftermath.

Fast forward to present day events. The 12-week long nationwide protests that began in October of 2019 culminated in the formation of a new coalition government led by Prime Minister Mustafa Al-Kadhimi. We are impressed with what we have seen so far. In our opinion, the new government has all the markings of the most inclusive government in Iraq’s short post-war history (in particular since the adoption of the 2005 constitution) – bringing together groups from across the varied political spectrum: Kurdish, Sunni, Turkmen and Shiite parties, including the large bloc led by popular cleric Muqtada al-Sadr. Kadhimi is also quite different from past heads of state. He has a non-political background (a journalist and human rights activist) and emerges from a younger generation of Iraqis (he is only 53 years old and is now one of the youngest heads of state across the Arab World). Despite this and as a result of his tenure as head of the country’s intelligence service during Iraq’s battle against ISIS, Kadhimi has developed strong relationships with many of the foreign powers that have influence over Iraq’s policies (including the United States, Iran, Turkey and Saudi Arabia). In short order, Kadhimi has managed to achieve sufficient parliamentary backing (something two preceding PM candidates were unsuccessful in accomlishing) and is now garnering strong popular support. Early days.

Most of all, we like the fact that Khadhimi does not belong to an established political party or is beholden to a foreign- or militia-backed group. He therefore must align the interests of disparate political and ethno-religious groups from a neutral and pragmatic position. Testament to this posture of neutrality is Kadhimi’s stated priorities as PM: a) he intends to dismantle the muhasasa system (ethno-religious-sectarian quota system that is at the root of political favoritism and self-serving corruption), b) push through long-planned but delayed structural economic reforms, c) return the huge number of internally displaced Iraqis to their homes and d) delicately rebalance the foreign political influence of pestering neighbors (Iran and the GCC) and old geopolitical patrons (the US). A tall order for any leader – to say the least.

Time will tell if Kadhimi is successful. We do however sit up and take notice when such a meaningful and potentially game-changing shift in leadership takes place, especially if the new leadership is presumably clean (his anti-corruption credentials are noteworthy), politically neutral and explicitly pro-reform. What caught our attention the most with Kadhimi’s mandate proclamations was his explicit recognition that Iraq needs to diversify away from its huge reliance on oil. Along with bridging the ethno-sectarian divide and thus tackling the root of corruption head-on, we believe that finally addressing Iraq’s stubborn ‘resource curse’, are the two most important and fundamental issues that Iraq faces as it transitions.

We have always believed that developing countries in transition like Iraq only adopt deep and generational structural reforms when they absolutely need to (not necessarily when they ‘can’). The more adverse the situation a country finds itself in, typically the stronger the anchor tends to be for deep and lasting reforms. Iraq’s ‘tragedy’ of the past 40+ years has created precisely the setting for this kind of anchored reform environment. Add to this cocktail the residual effects of decades of sanctions, dilapidated post-war infrastructure, endemic corruption, chronic political unrest, and a growing outbreak of COVID-19 in the past 6 months, and this may be the recipe for a potent catharsis moment.

One thing that most analysts do not acknowledge loudly enough is the fact that Iraqi nationalism has (so far) survived all of these existential challenges, extreme tensions and sporadic outbreaks of violence. An objective observer of history could argue that this nationalist resilience has persisted since at least 1933. Despite the plethora of predictions of the country’s destined split-up along major ethno-sectarian lines, the federal Iraqi state has surprisingly survived, albeit in an acutely decentralized form. The country, through a deliberate and iterative process over the past 15 years has managed to maintain some semblance of a functional nation state- something that is quite impressive (for most – it is downright surprising) in light of all the big cleavages.

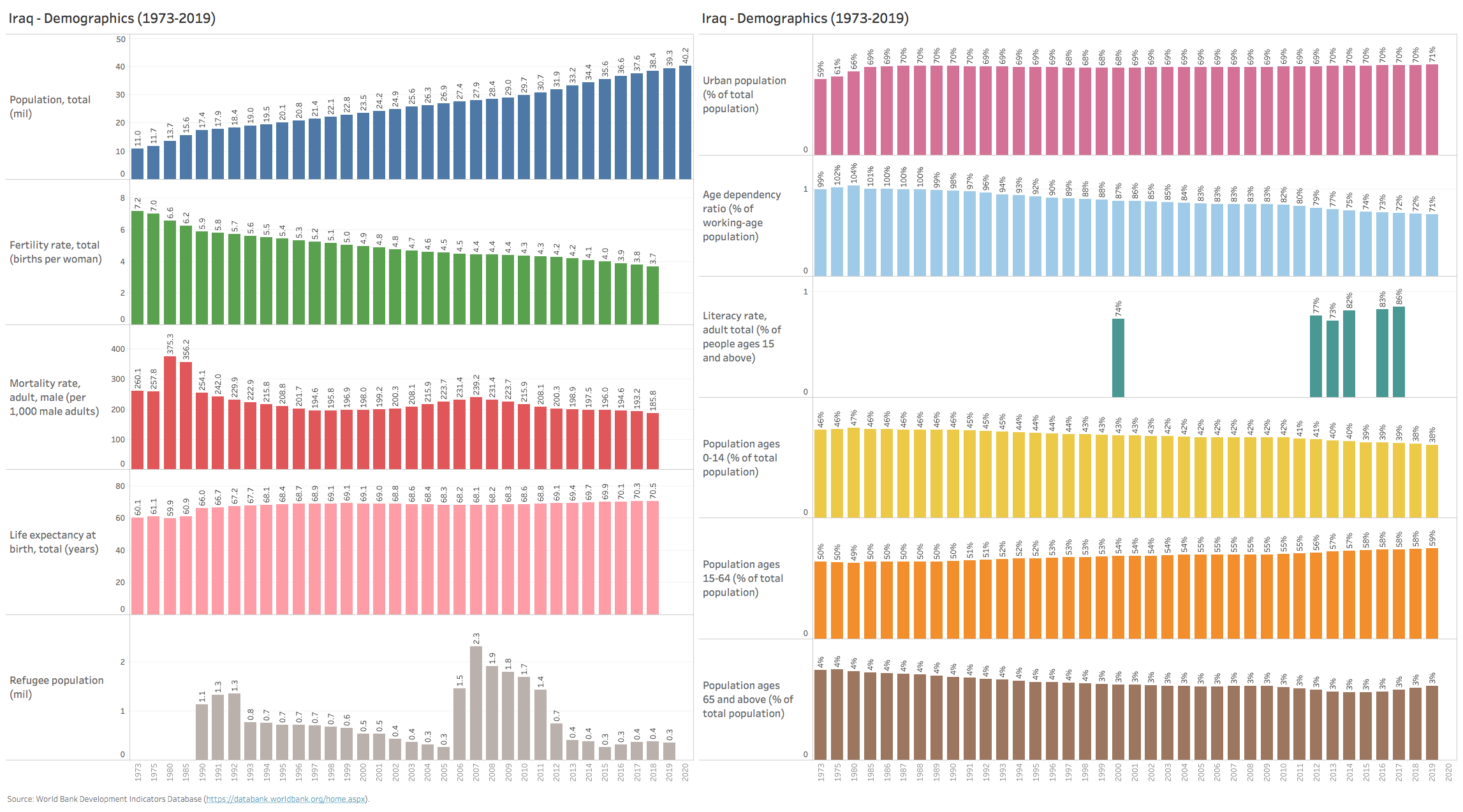

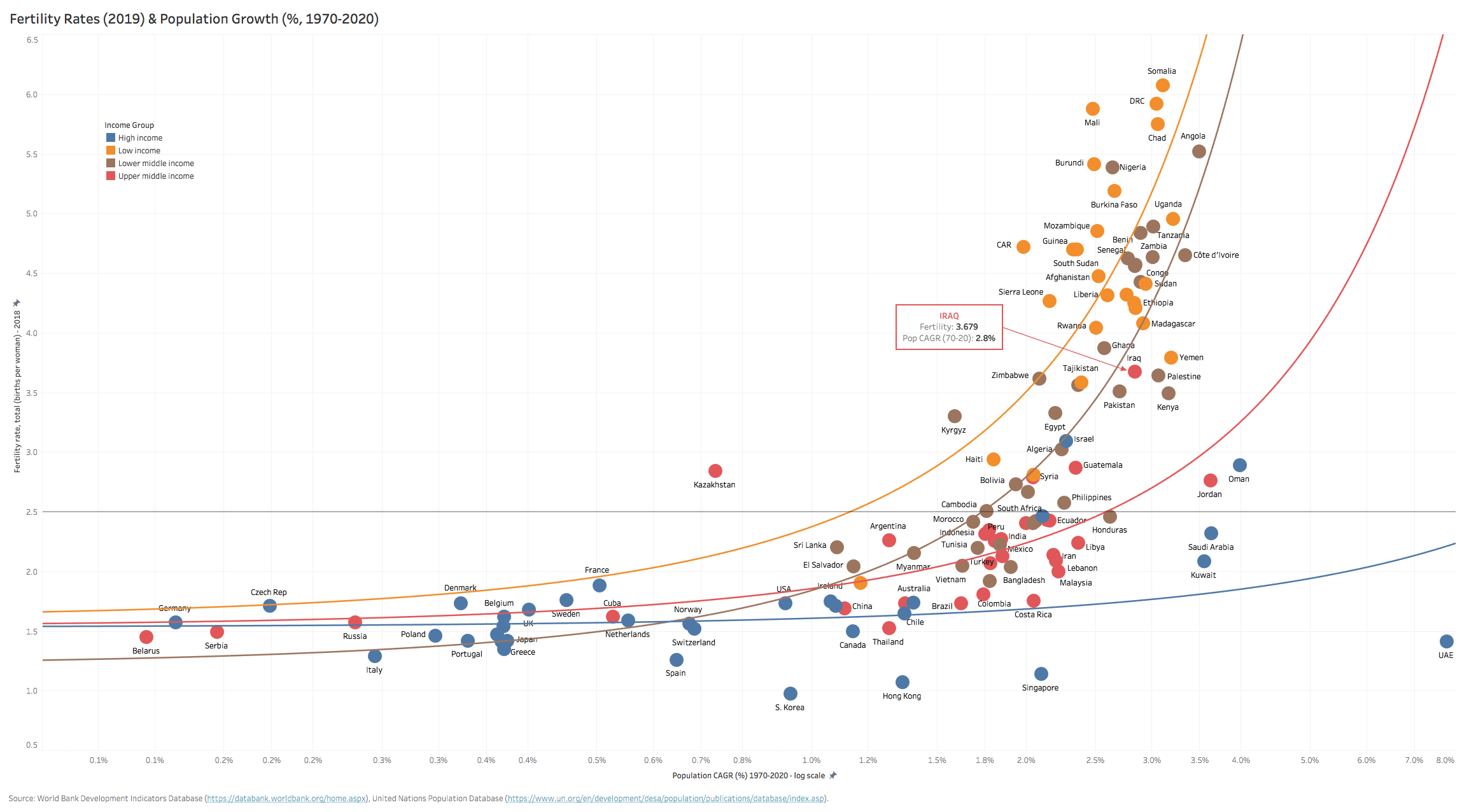

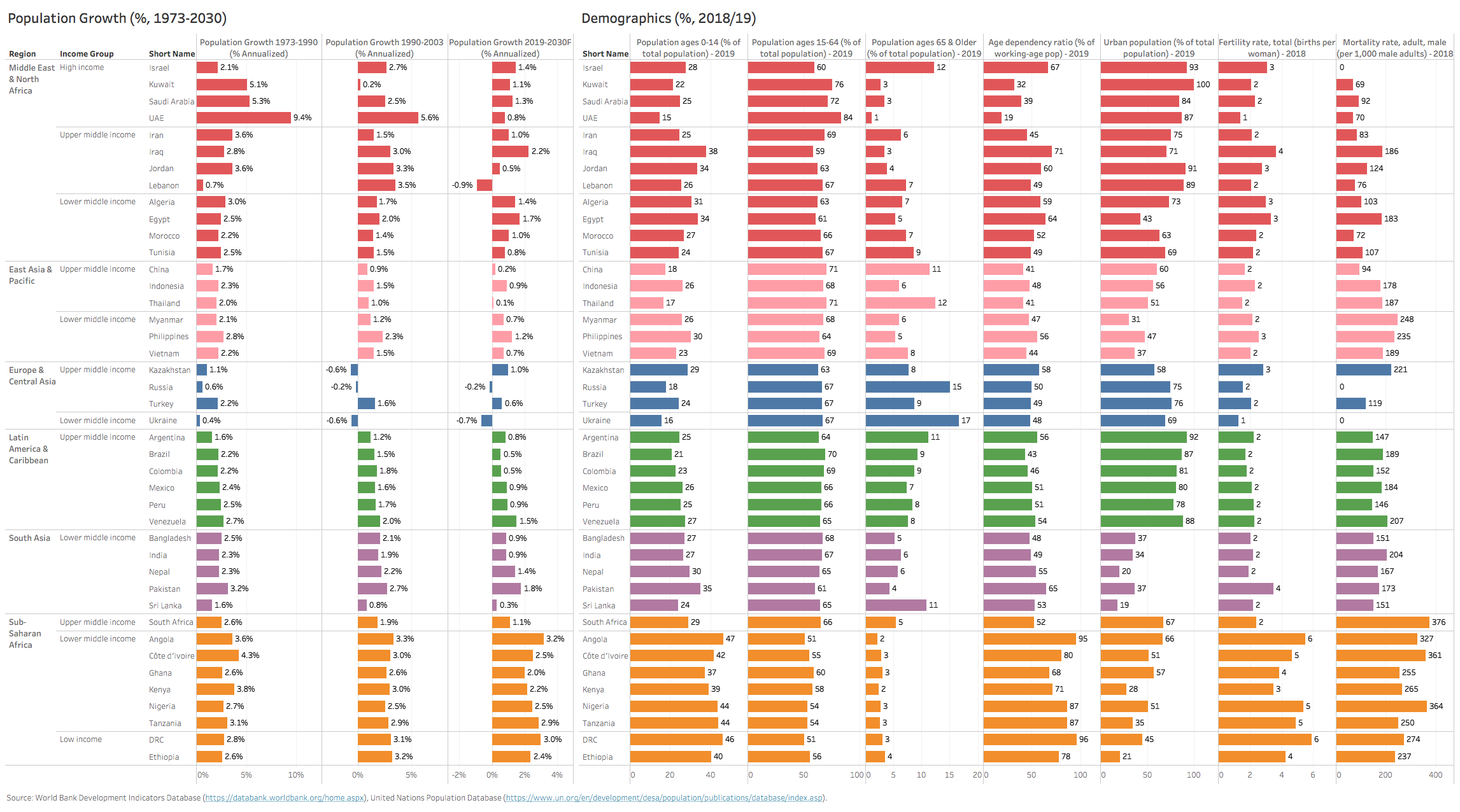

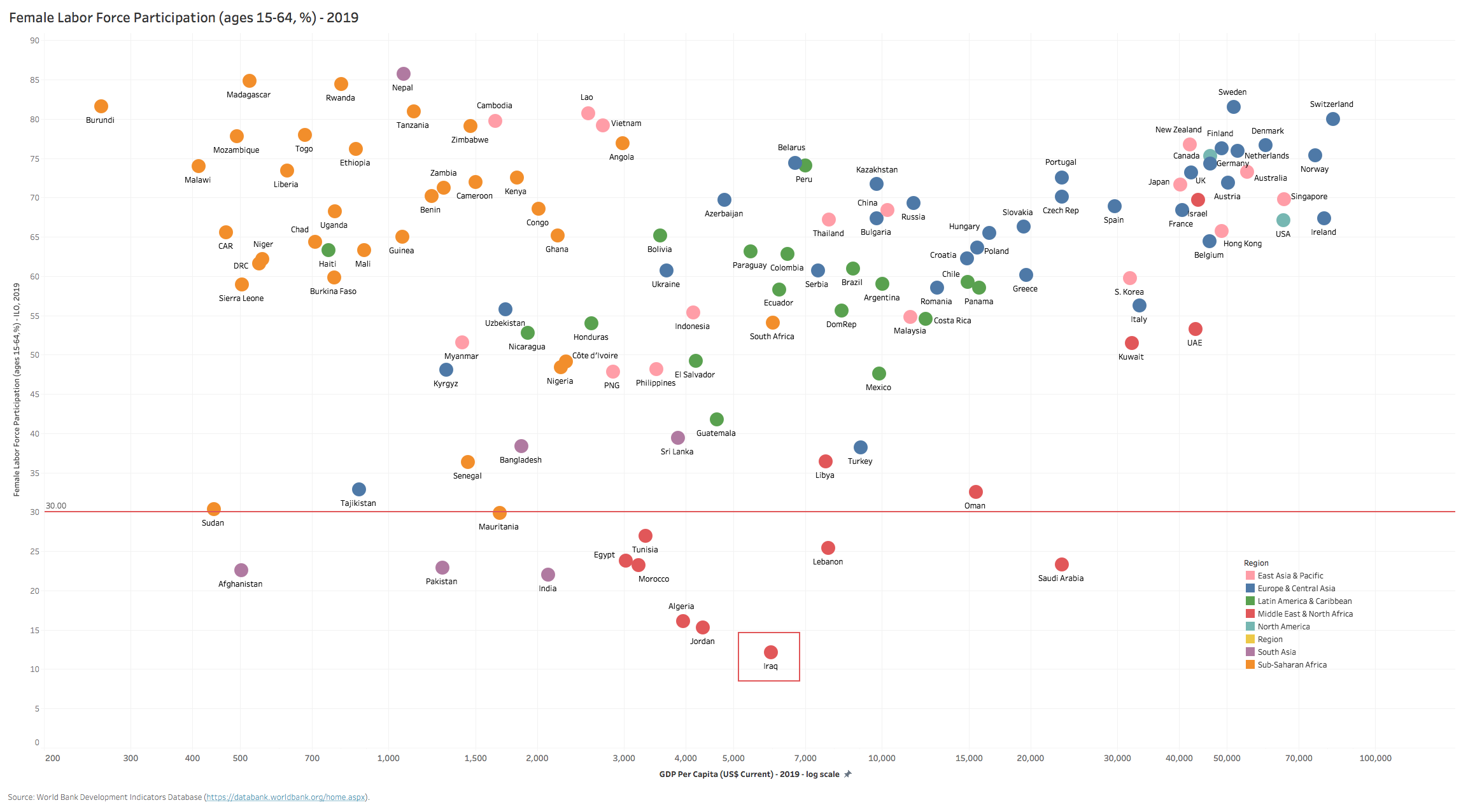

Demographics

Furthermore, it is important to also take note of Iraq’s unique demographics (Charts 5-9 below). The median age of an Iraqi citizen is less than 20 years old (38% are below the age of 15, 65% below the age of 25). So, the majority of Iraqis were born and grew into adulthood during a time where instability and crisis was the norm. Any shift from the status quo would be a welcome departure for young Iraqis (ages 15-24) who command the highest representation in the workforce across Arabia (34% vs. the likes of Egypt at 28%). Due in large part to the demographic boom and youth bulge of the past 25 years, the population has doubled from 20mil to close to 40mil while the country’s age-dependency ratio has fallen from 92% to 70%. Despite this, Iraq still has one of the highest fertility rates of any upper-middle income country at 3.7 births/woman, a level that is more in-line with a demographic curve of a low-income African nation. As urbanization rates rise (from 70% to 80%+) and population growth slows down, more Iraqis are entering the workforce and the aspirational consuming class – a huge anchor for productivity growth if they are provided jobs. Finally, the generation of Iraqis that is older than the country’s new prime minister (those 65 or older) currently account for less than 3.5% of the population. This tiny minority is aging, spent and gradually retiring or leaving the scene over the next decade. The future of Iraq is simply no longer theirs to claim.

Chart 5: Iraq Demographics (1973-2019)

Chart 6: Fertility Rates Worldwide vs. Population Growth (1970-2020)

Chart 7: The Youth Bulge in MENA (1950-2050F)

Chart 8: Working Age & Older Populations Across MENA (1950-2050F)

Chart 9: Population Growth & Demographics Benchmarking (1973-2030)

Security & Perceptions of Governance

Despite the improved security situation in Iraq since the aftermath of the 2003 post-war conflict and the 2014-2017 ISIS insurgency, deep ethno-sectarian fissures remain, ISIS’ re-emergence continues to be a lingering security threat and the deep-rooted influence of Iran and its local militia-backed proxies continue to be potent destabilizing factors. We view these threats both as prominent risks, but also as strong anchors for the reinforcement of the federal security apparatus and continuing police and security force reform. Khadhimi’s intelligence background and leadership in defeating ISIS is a major asset here as well. The lessons from 2010-2014 when the security apparatus was neglected and pillaged by the Maliki-led government, only to be over-run by a small ISIS insurgency force are still front of mind for all Iraqis.

With the security threats dissipating somewhat though, past governments’ excuses for poor reform performance begin to fall apart. Emma Sky, in a recent interview, describes the “weird symbiotic relationship” between terrorist threats like ISIS and corrupt politicians: “each claimed to save their people from the other. Now that the security threat has come down, there is no longer an excuse from politicians not to be delivering services….If the government fails to reform, then it becomes more difficult to point to scapegoats and excuses.” Reducing the ISIS threat in a sense has fortified the strength of the reform anchor and forcibly aligned the incentives of government and the people.

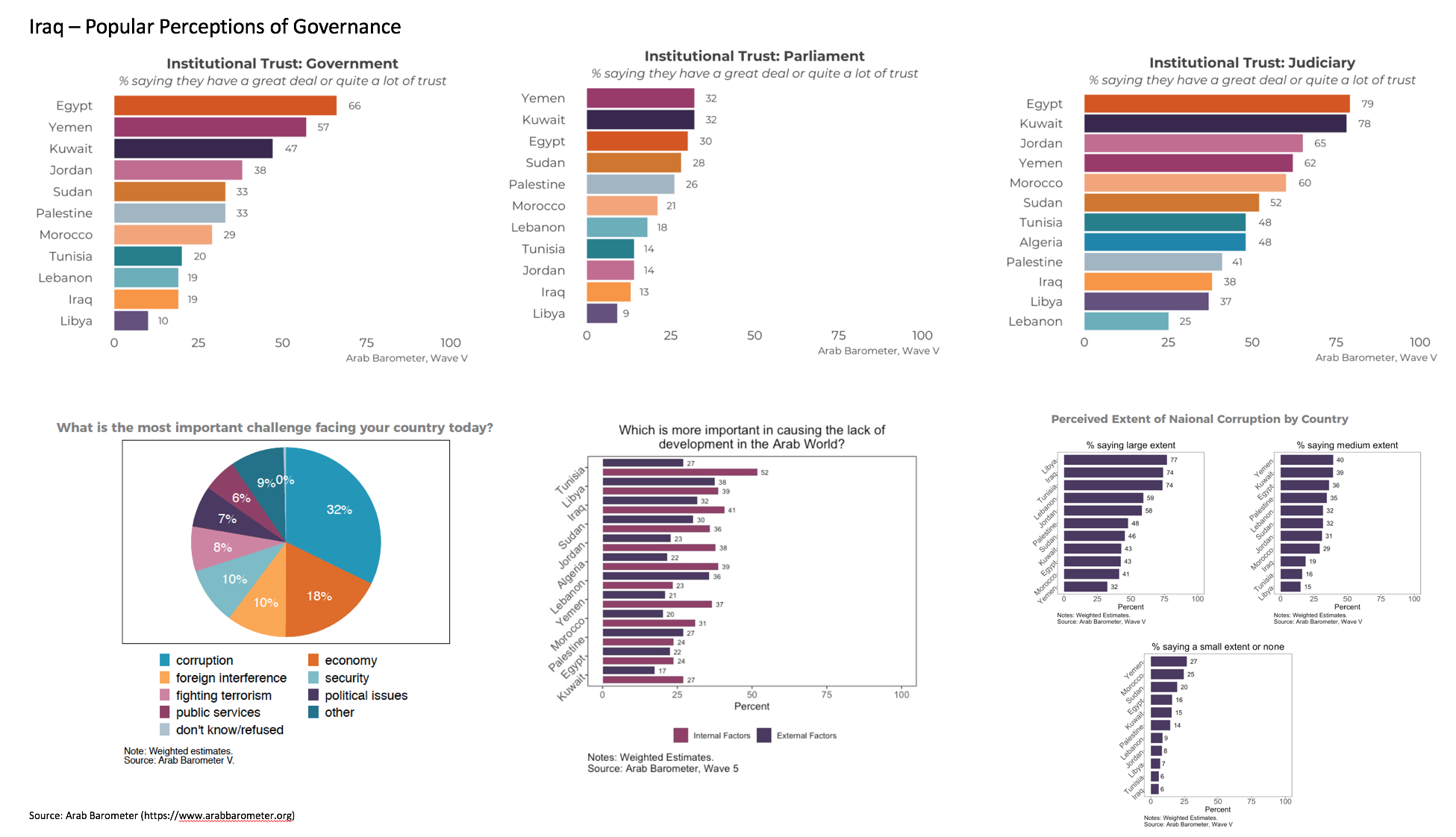

Finally, what gives us the most conviction for expecting important change is that the younger Iraqi generations are now speaking up and expressing their deep distrust of past governments. Recent polling by Arab Barometer in 2019/20 is testament to these trends (Chart 10 below). Only 19% of Iraqi’s polled had trust in the government while a mere 13% trusted parliament (on both counts Iraq is ranked second to last in Arabia, ahead of only Libya). When polled on the most important challenges facing Iraq, nearly a third of respondents named corruption as the leading challenge, with the economy ranking a close second (18%), while both featured notably higher rankings than security (10%). The majority of Iraqis also attribute the leading cause of poor development to be ‘internal’ vs. ‘external’ – in sharp contrast to other fragile states like Lebanon where external factors have a much higher attribution.

Chart 10: Iraq – Popular Perceptions of Governance

Chart 11: Iraq – Popular Perceptions of Governance

On a general perception of national corruption, 74% of Iraqis polled believed that corruption plays a large role in everyday life. Chart 11 above shows a snapshot of recent polling conducted by a local pollster (Mustakella, 2019) which echoes much of the data from Arab Barometer. Notable here is the trend in sentiment from 2010-2019 of those who believed Iraq was heading in the wrong direction: rising from 45% in 2010 to 75% in 2019. Other notable poll results include: a) 79% of Iraqis do not believe that the May 2019 elections were free and fair, b) only 41% of Iraqis trust religious institutions (down from 80% in 2014), c) only a third of Shia Iraqi respondents believed that Iran remains a reliable partner (down from 75% in 2016), d) 74% of Iraqis believe that they are not treated equally with other citizens in their country, and e) an overwhelming majority (76%) of Iraqis supported the protests of 2019. Contrast these polling results to the ethnic, religious and sectarian profile for Iraq discussed earlier, and the gravity of the situation starts to become clearer.

In light of this snapshot of popular sentiment, the October 2019 demonstrations should not have been surprising to onlookers. They reflect loudly the alarming levels and trend of negative perception of governance in the country. Iraq reached its metaphorical boiling point in 2019/20 as a result and this in turn catalyzed political change. But as with past Arab spring uprisings, the ultimate outcome remains risky and deeply uncertain.

ECONOMIC TRANSITION

Pre-War Economic History

The historical economic picture for Iraq, for most of its modern history prior to the exploitation of its oil resources in the 1970s, moved largely in tandem with the volatile and noisy political backdrop (reference Table 1 & Charts 1 & 2 above for a chronology of key events). After independence from British colonial rule and through several revolutions, countless coups, experiments with Nasserist-style socialism, pan-Arab federalism and Iraqi nationalism, the country was never able (nor stable enough) to pursue broad and deep structural reforms and the institution-building that is a natural by-product. As a result, Iraq never really managed to ground itself in a sustainable economic policy framework for the better part of eight decades. Similar to many Arab countries’ experiences during the post-colonial period, Iraq’s history is full of missed opportunities and unclaimed potential.

This disappointing outcome was particularly the case in the period directly after independence from Britain in 1958 when Iraq untethered from the Sterling area and lost its colonial anchor of governance. In the subsequent years before oil became the economic engine for Iraq’s rentier state (beginning in 1973 after the oil sector was nationalized), Iraq’s economic performance for the better part of the period of 1958-1973 was decent, with episodic bouts of growth mainly derived from higher oil revenues which began to accelerate in the mid-1970s.

According to HBS’s Fabbe, “Growth in government spending, particularly for the military, accelerated [only] by the late 1960s, but oil revenues permitted Iraq to incur minimal levels of foreign and domestic debt.” Frank Gunter, a Lehigh University economist and retired US marine that worked for the coalition in Iraq from 2005-2009, surmised that “from 1950-1979, there was a steady rise in per capita incomes…the latter years [distinguished] by the highest living standards ever achieved by the Iraqi people.” This was despite an almost tripling in Iraq’s population (7mil to 21mil from 1960-1979), but obviously flattered by the sharp rise in oil prices in 1979-80. Income per capita (real US$) rose from sub-$500 in 1973 to just shy of $2,000 by 1978, propelled almost exclusively by rising oil rents that reached as high as 65% in 1974. According to Gunter’s own calculations, in PPP terms, Iraqi per capita income was estimated to have risen to nearly $20,000 by 1979-80 more than doubling from the early 1970s.

On the structural front however, apart from the short stint shortly after the 1958 revolution (1958-63) when important economic reforms were pushed through by the Qasim-led “Iraq First” populist/nationalist policies, this three-decade period of post-colonial rule was in retrospect, a lost era. Iraq adopted little if any industrialization or productivity-enhancing policies. Qasim was overthrown in a 1963 bloody coup, and most, if not all, of his laissez faire policies were abandoned in favor of state nationalizations and the precursor for the hollowing-out of the private sector (1964 saw 30 leading industrial firms and all the private banks and insurance companies transferred to public sector ownership). This also ended up effectively weakening the entrepreneurial class in Iraq. According to Al Nasrawi, all of this was done under the banner of ‘social justice’ and to align Iraq more closely to the disastrous Egyptian-Nasserist socialist model ahead of a planned federation with Egypt & Syria.

Towards the late 1970s however, but well before the Baath party began to weaken the entrepreneurial environment with a system of party favoritism and before Dutch disease fully set in and inflated the dinar, Iraq was only a minor exporter of food and boasted only a meager industrial base that was built on the foundation of import substitution. The planned union with Egypt never materialized when the Baath party rose to power in 1968 as it adopted an explicit strategy of establishing a nationalist, socialist economic system – thereby shrinking the private sector even further. By the early 1980s, and with oil revenues fueling the growth of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which by then controlled all manufacturing and trade, the public sector overtook the private sector in size. Despite a rushed privatization drive that was instituted in the mid-1980s to shore up reserves due to the expensive war with Iran, the Iraqi private sector never really recovered from past decades’ debasement.

With the largesse of oil rents that ensued after 1973, Iraq experienced an impressive expansion of the state apparatus, fueling massive government spending on arms and infrastructure. The Baath party also spent heavily on healthcare, education and large state subsidies, though most of the recipient sectors remained dominated by SOEs. Public investment to GDP was as high as 27% in 1973, though the ratio of private to public investment declined in the 1970s as the state expanded the scope of its activities. By the mid-1970s, Iraq’s defense spending grew to account for the majority of the government budget (from $3.1 billion in 1975 to $20 billion in 1980 or 39% of GDP). The period ending in 1979 also marked the peak in real per capita income (PCI) at the time, with PCI nearly reaching $4,000 per person in 1980, a 35% annualized growth rate vs. 1973 (despite very high population growth of 3.2%) and over 4x the average for middle income states ($700). Chart 12 below with data from the World Bank and US EIA illustrates these trends. According to Fabbe’s assessment of Iraq during this period, “with oil generating more than 95% of export earnings and over 60% of GDP in some years, while absorbing only about 2%-3% of the Iraqi labor force, Iraq became the quintessential rentier state“.

Chart 12: Iraq – Resource Intensity & Per capita Income Growth (1973-2019)

That is essentially Iraq’s pre-war economic picture as we see it. The years that followed, up to the 2003 US invasion, were characterized by huge economic distortions and dislocations, clearly manifested by years of war, internal strife and sanctions. Any long-term economic development plans (e.g. industrial deepening or the launch of a manufacturing base) were subordinated to either the war-time objectives or to circumvent the ensuing sanctions regime. As a result, any semblance of a robust private sector was largely absent, and the informal economy dominated the picture as a result. Testament to this is the fact that manufacturing as a share of GDP fell precipitously from a 1985 high of 9.9% to as low as 1% in 2003, without ever fully recovering since then (see Chart 13 below).

Chart 13: Iraq Sectors as a Percentage of GDP (1970-2020)

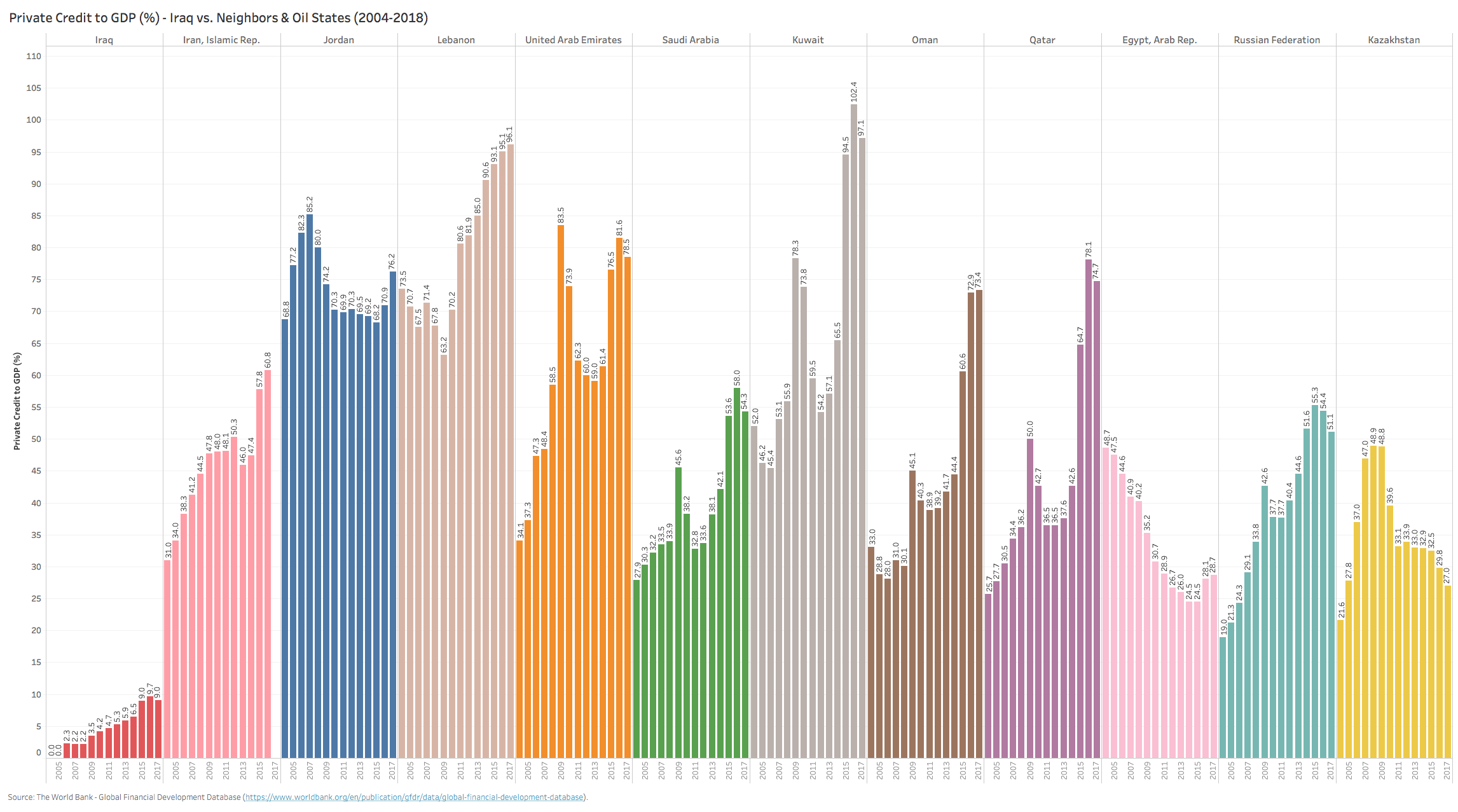

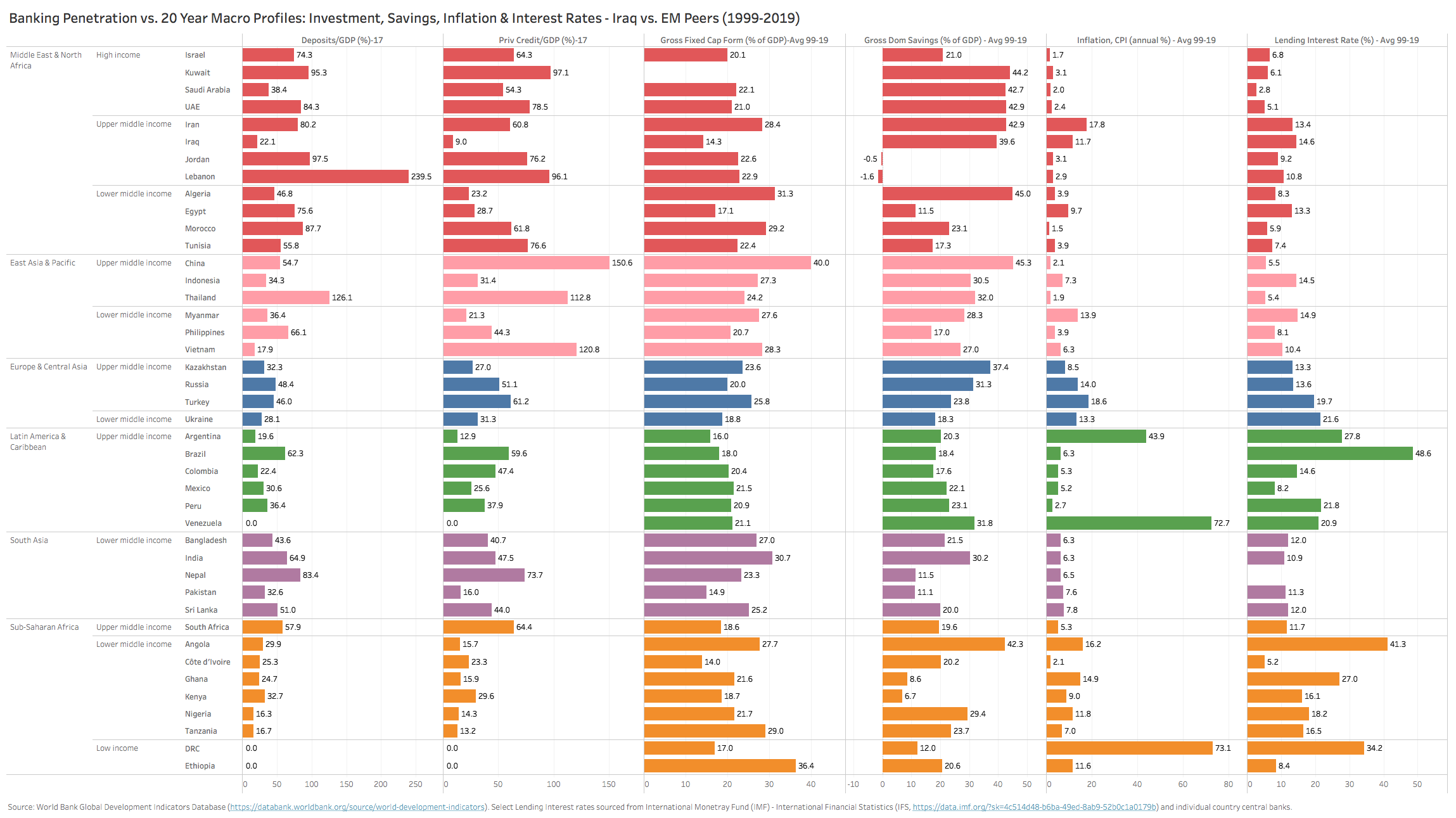

We believe this historical backdrop is especially important in order to understand the root cause of the slow pace of the private sector’s revival since 2003. For us, it goes a long way to explaining why various aspects of reform like state bank restructuring have yet to be completed, thereby postponing the full potential of private-sector banking. It also explains the incredibly paranoid attitude towards foreign private investment and why easy obstacles like foreign share custody for stocks as a minor example remains absent in the Iraqi capital market infrastructure. The longstanding historical dominance of the SOE ecosystem in Iraq and the generally apathetic culture towards private enterprise has played a huge role in delaying the broad liberalization of the Iraqi economy.

The Cost of Iraq’s War-Time Adventurism

By the time the bloody eight-year war (1980-88) with Iran was over, due to rampant military spending and huge deficits during this period, Iraq’s debt had ballooned to almost $80bil (50% of GDP), the country virtually exhausted its foreign currency reserves while inflation spiked from 95% in 1980 to 369% by 1988. The collapse in oil prices between 1986-1988 (despite an impressive recovery in production) had meant that oil revenues were only $11 billion, less than half of the 1980 levels and insufficient to continue funding the large patronage system and state subsidies. Iraq primarily financed the war with debt from Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, totaling over $40 billion and made up roughly half their debt of $75 billion in 1989. By this time, about 55% of Iraq’s oil revenues went to service this debt. All in, the Iraq-Iran war had cost the country $453 billion in losses (250% of its cumulative 57-year oil revenues). Add to this Iran’s own losses of $644 billion and the total cost of the war for both sides eclipsed $1 trillion. The numbers are still staggering in magnitude.

The decision to invade Kuwait in 1990 that followed the Iran-Iraq war two years hence was a direct consequence of the war’s painful economic losses and an obvious act of desperation by Saddam Hussein to recover ‘lost ground’ (literally in terms of territory, metaphorically in terms of Kuwait’s oil reserves and capital). The 1991 US-led liberation that ensued destroyed a major portion of Iraq’s infrastructure (military, civilian and oil capacity). In the ensuing 12 months, oil production fell by 86%, imports dropped by 90% and exports by 97%. Hyperinflation set in during this period, reaching 1,000%-2,000% (annual), driving the real value of the Iraqi dinar into a free-fall. The dinar’s longstanding peg to the US$ at 3.2-3.4 IQD/$ (1973-1990) broke down in 1990 into three separate exchange rates with a free market rate that eventually depreciated to as low as 2,000 IQD/$ by 1992 (note: the official dinar exchange rate remained pegged until 2003 and eventually settled at a rate of 1,450 by 2005 and was later revalued to 1,170-1,180 by 2010 as inflation dropped to single digits and foreign reserves built up). By the end of this period, total debt had reached $86 billion (540% of GDP) and foreign reserves were all but exhausted. All in, the Gulf War of 1990-91 cost Iraq an additional $232 billion in damaged infrastructure and economic opportunity cost. Alnasrawi estimated in 1994 that the economic cost of both wars, inclusive of war reparations and accumulated debt to have been as high as $586 billion or 60x Iraq’s 1993 GDP and equivalent to China’s GDP in 1994. This conservative estimate did not include the opportunity cost of lost oil revenues, exhaustion of foreign reserves, lost non-oil output or the massive brain drain that resulted from emigration during this period.

Looking from the perspective of the average Iraqi, the toll was arguably far greater. Both wars cost upwards of half a million Iraqi lives (close to 17% of the labor force at the time) with millions more displaced or wounded. The impact on average standards of living was also incredibly painful. The 13-year period after the UN embargo and sanctions regime took hold pulled the Iraqi real per capita income (measured in current US$s) to nearly ground zero. Several estimates of where real GDP per capita stood in 1995 put it at a mere $250-$450 – possibly below that of rural India at the time. According to Gunter, on a PPP basis, per capita income fell to as low as $2,500 in the early 1990s, translating into a nearly 87% drop from the 1979-80 peak and well below Iraqi average income levels last seen in the late 1950s. This was not surprising as the UN embargo had effectively shut down Iraq’s exports, driving oil export revenue per capita (in real terms) from $2,355 in 1980 to as low as $232 by 1997 (see Charts 1 & 2 above). This decade of war-time adventurism sent the Iraqi economy into a massive financial hole and erased almost 50 years of income growth.

Post 2003 – A New Beginning

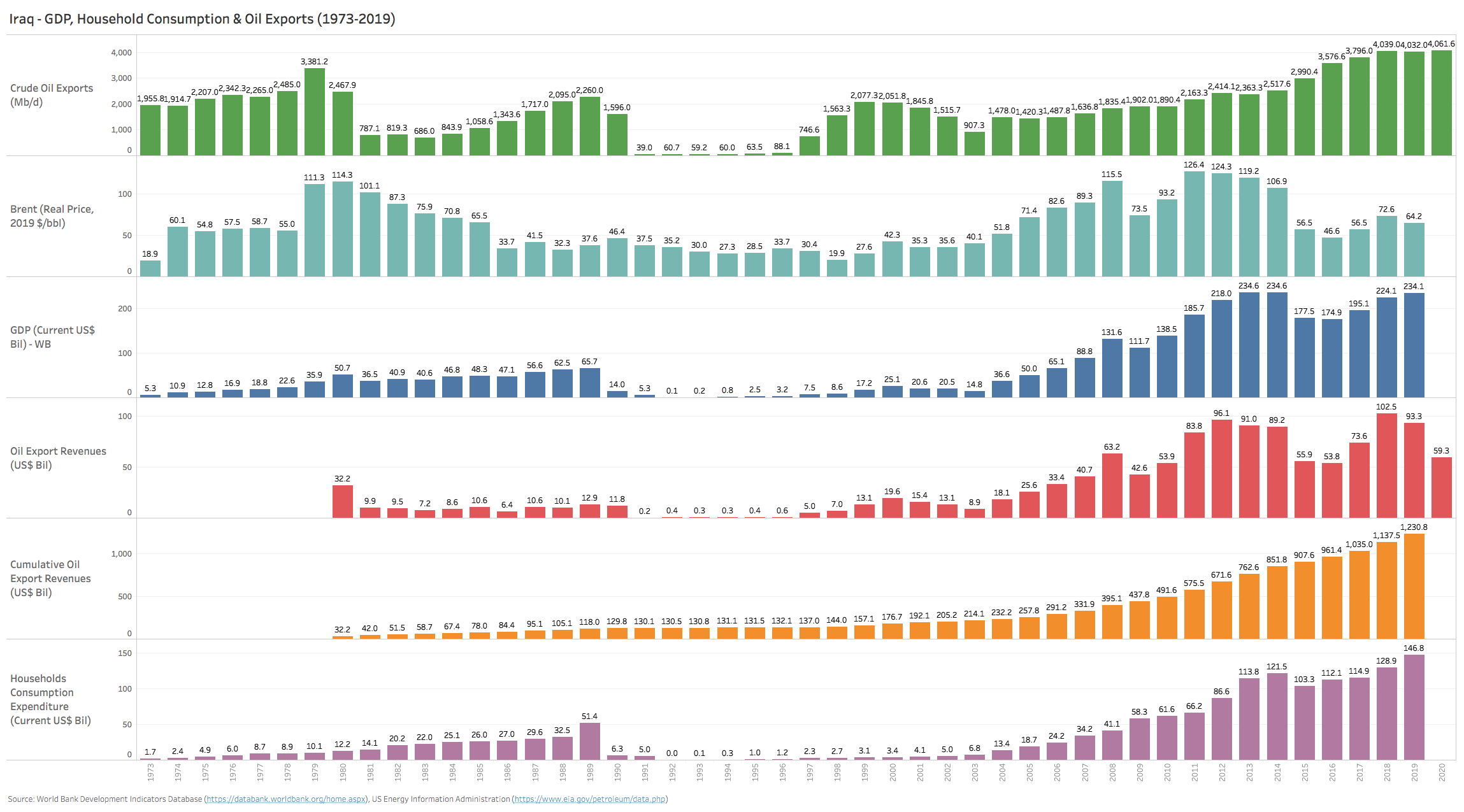

Fast forward to the post-2003 period, the hydrocarbon sector was effectively allowed to decouple from the overall economy due to the CPA’s strong emphasis on aggressively resuscitating Iraq’s oil production. The recovery in production and GDP from 2003 to 2020 was nothing short of remarkable, and this occurred despite the political upheaval that Iraq experienced in the aftermath of the US invasion and subsequent civil war, insurgencies and overall governance dysfunctionality. Oil production rose from 1.3mbpd to nearly 4.9mbpd by 2019 (an all-time record), while GDP per capita went up by a factor of 11.5x (from $616 in 2003 to over $7,000 by 2013 – though still shy of Gunter’s estimate for Iraq’s PPP peak in 1979). Household spending, although recovering swiftly from the 2003 lows, exhibited a flatter slope ($265 per capita to $3,400 in 2013), while oil export revenue per capita actually began to stagnate and then fall by 2016. This divergence is due to both: a) high and rising population growth rate (averaging close to 3% during this decade and reaching as high as 3.9% in 2013; Iraq’s population added 7.6mil during this period – a 30% rise) and b) the reality of weaker and more volatile consumer sentiment during much of this recovery period.

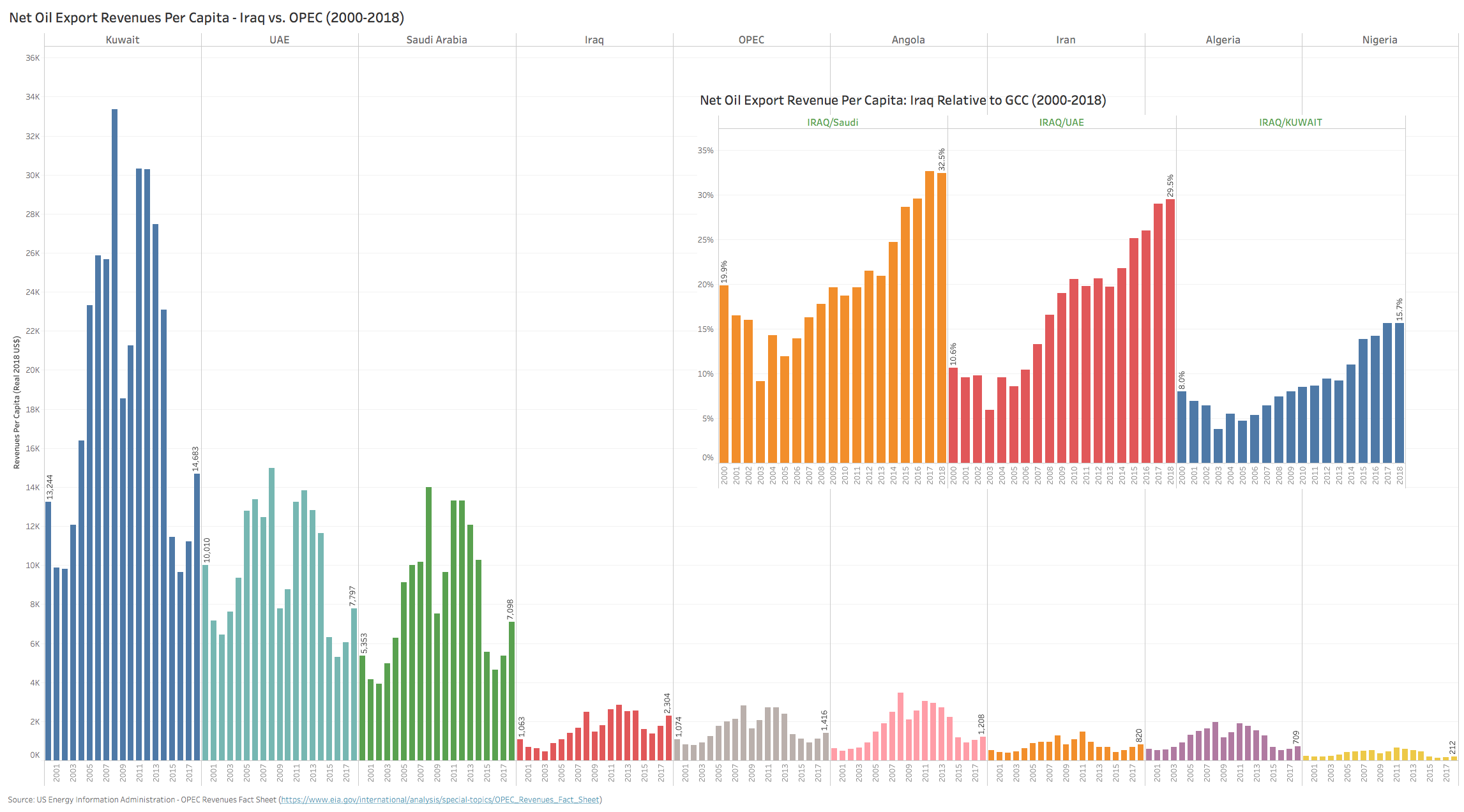

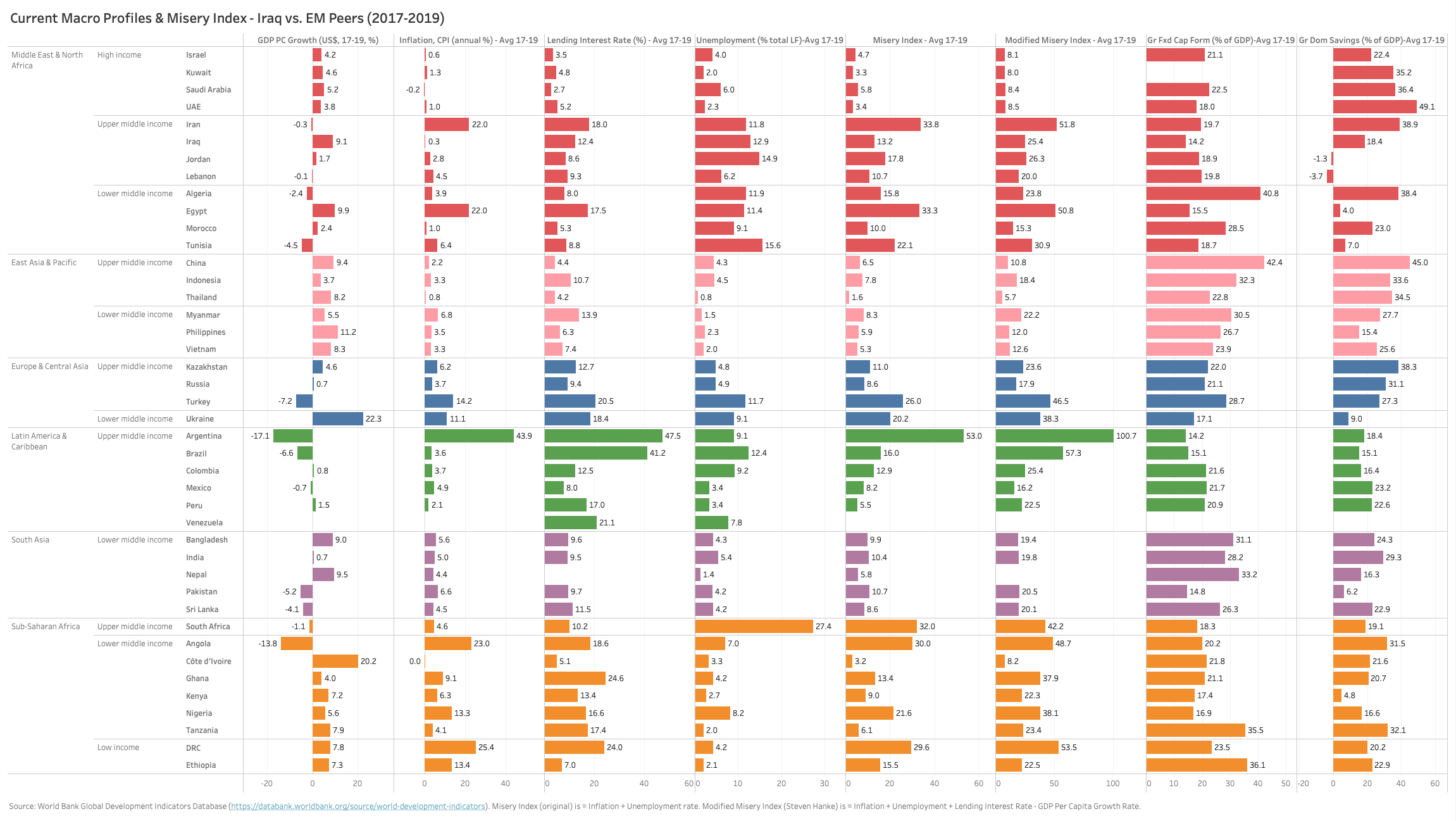

While the lackluster recovery in consumer spending is not surprising due to an unstable security environment and the slow ramp-up of core infrastructure rehabilitation (the chronic power sector deficit is a prime and noteworthy example which we discuss later in the note), the fall in per capita oil export revenues is however an area of structural concern. Unlike the GCC states or many of its OPEC peers, Iraq continues to punch below its weight when it comes to oil revenues per capita, with less than a third of Saudi’s average and only 16% of Kuwait’s (Chart 14 below). If Iraq continues to be a ‘one-trick-pony’ in terms of its extreme reliance on oil revenues (60% of GDP, 92% of government revenue and 99% of exports), per capita oil revenues will need to at least rise above population growth (2.3%) in order to just maintain the current standard of living. During oil shocks like the one being experienced in 2020, the expected impact to the budget is material, with a projected deficit of 23%-29% in 2020 (assuming a fiscal breakeven oil price of $60/bbl) and a shortfall in covering just the $52 billion of public sector salaries and pensions alone (see Chart 15 below).

Chart 14: Net Oil Export Revenue Per Capita – Iraq vs. OPEC (2000-2018)

Chart 15: Iraq – Revenue, Deficits & Non-Oil GDP (2005-2021) – IMF

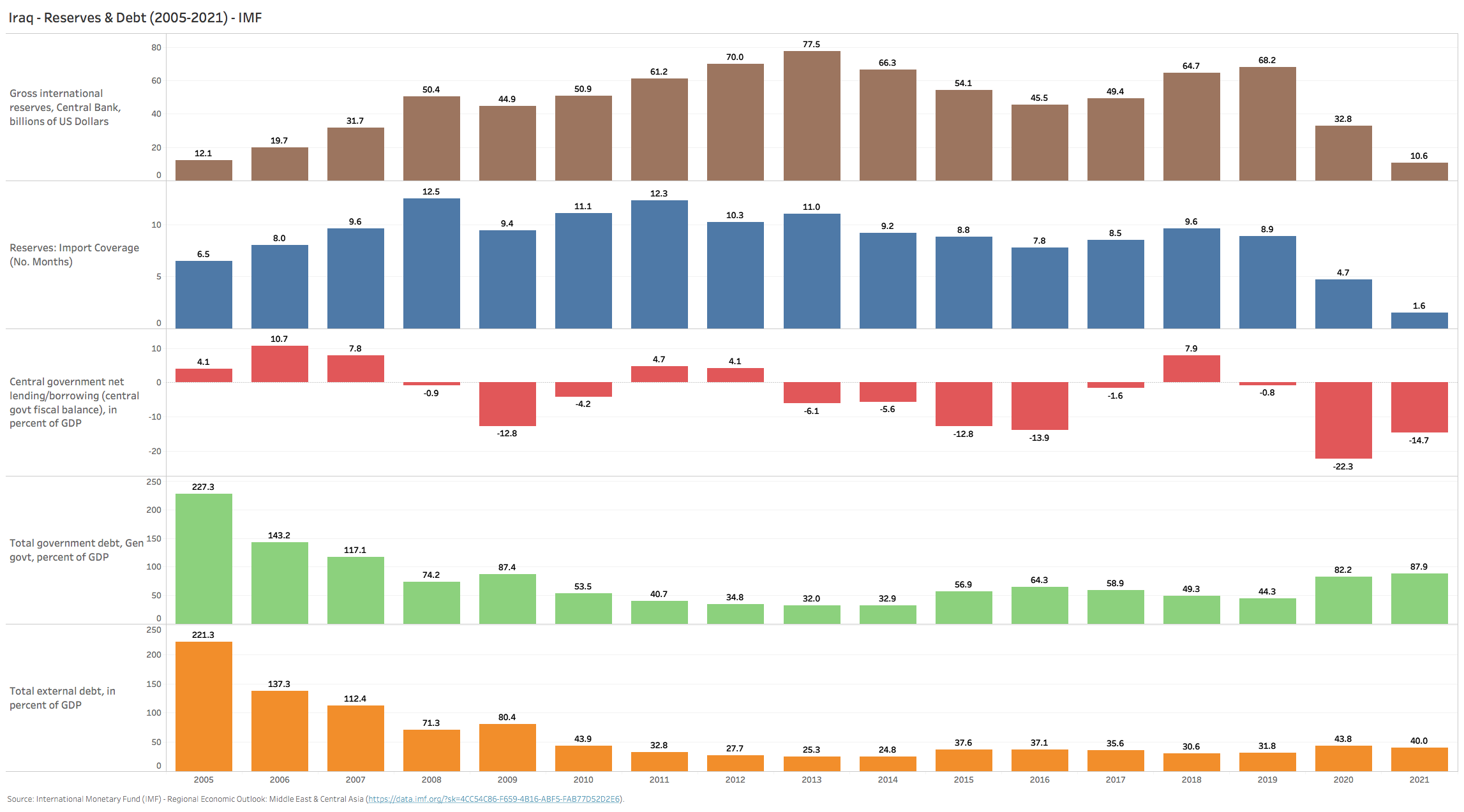

Finally, the IMF expects international reserves to more than halve in 2020 ($68bil to $33bil) with import coverage dropping to a dangerous 4.7 months (1.6 months in 2021). A sharp rise in government borrowing will be needed to plug these massive funding gaps, with total debt to GDP expected to nearly double (44% to 82% – Chart 16). With non-oil GDP growth expected to be down as much as 9% in 2020 vs. oil GDP contraction of 2.3% (IMF projections), there will be little support from the moribund non-oil economy. This seriously calls into question Iraq’s production cut commitments to OPEC in 2020 and beyond. If there ever was a need for more hard evidence to support diversification away from hydrocarbons, 2020 is one heck of a wake-up call.

Chart 16: Iraq- Reserves & Debt (2005-2021) – IMF

Iraq’s Resource Curse

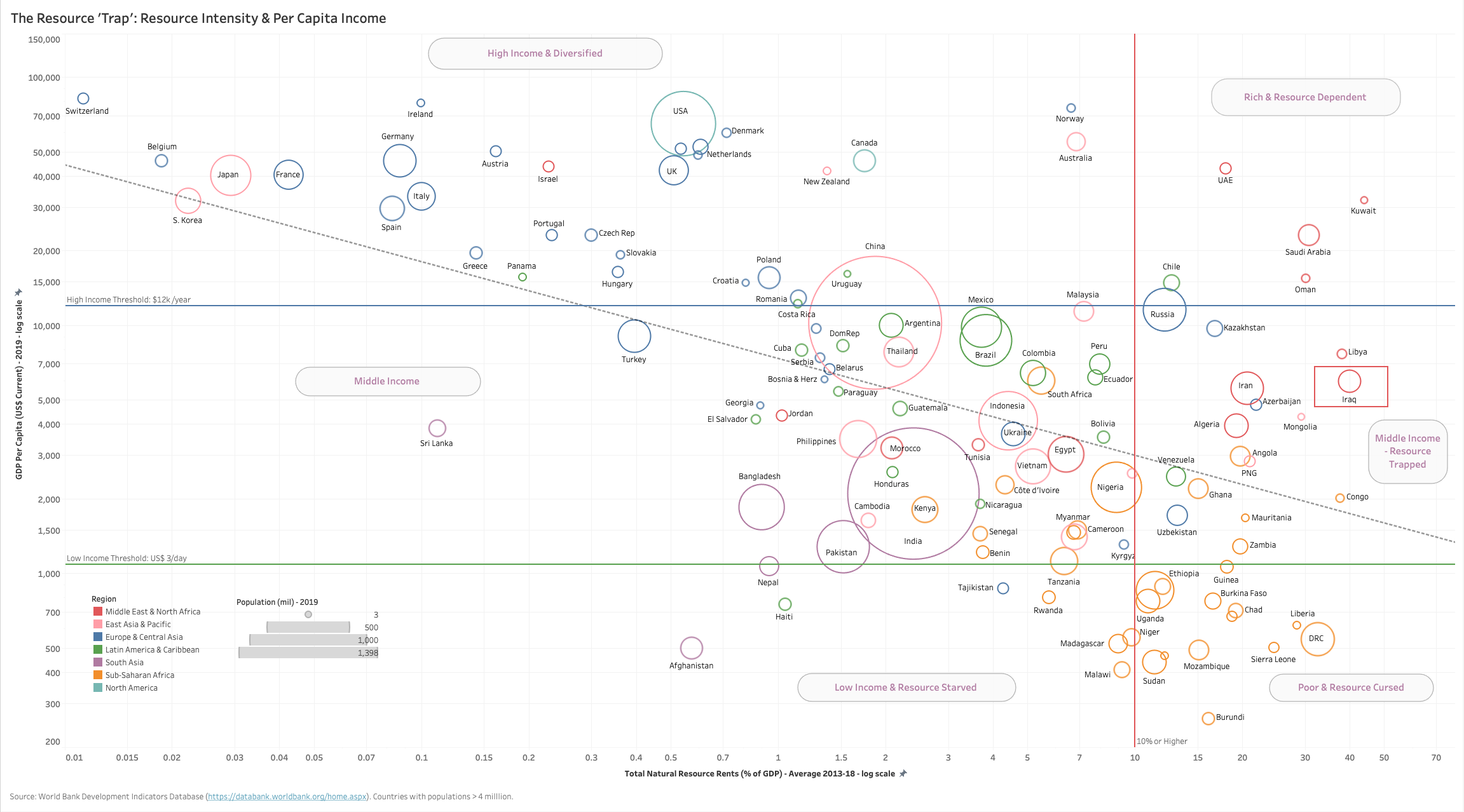

The further intensification of Iraq’s oil dependency that resulted during this period (post 2003 resource rents as a percent of GDP declined from a staggering 64% in 2004 to 46% by 2018, during a time where Iraqi GDP rose by a factor of 6.5x and compounded at over 13% in real terms), cemented Iraq’s place in the quadrant economists call the ‘Resource Trap’ (Chart 17 below). If you look at the middle-income countries that accompany Iraq in this unflattering group (Iran, Algeria, Libya, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Mongolia, Papua New Guinea, Angola, Ghana, Mauritania, Zambia, Congo and Venezuela – red bars), several commonalities emerge when looking at a multi-decade growth profile (1990-2018; see Chart 18 below for a benchmarking of this group).

Chart 17: The ‘Resource Trap’: Resource Intensity & Per Capita Income (2018/19)

Chart 18: ‘Resource Trapped’ Countries Benchmarking (1990-2018)

Most of the three-decade growth for the majority of countries in this group can be attributed to the resource sector, with resource-rent growth in most cases eclipsing overall GDP growth (in some cases like Iraq & Venezuela, the differential is quite large). This is also reflected in non-resource growth rates that are almost unanimously below overall GDP growth rates (Angola is the lone exception). Pull forward to the last five years (2013-2018) during a period of weaker commodity prices and the effect of the resource curse is evident in negative (> -5% for many) GDP growth rates for almost all of the ‘trapped’ peer group, with an even more pronounced contraction in the non-resource sector for most.

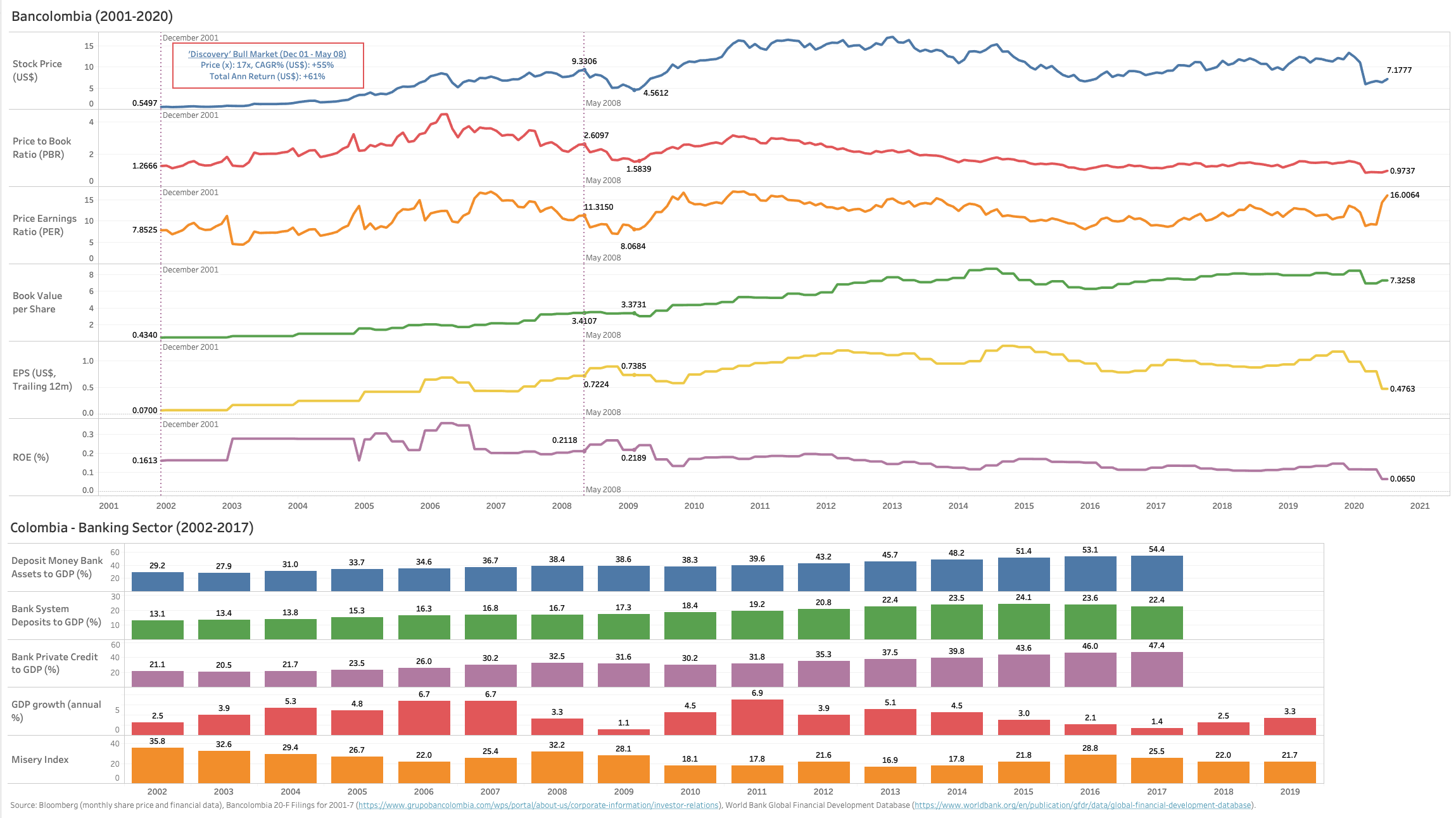

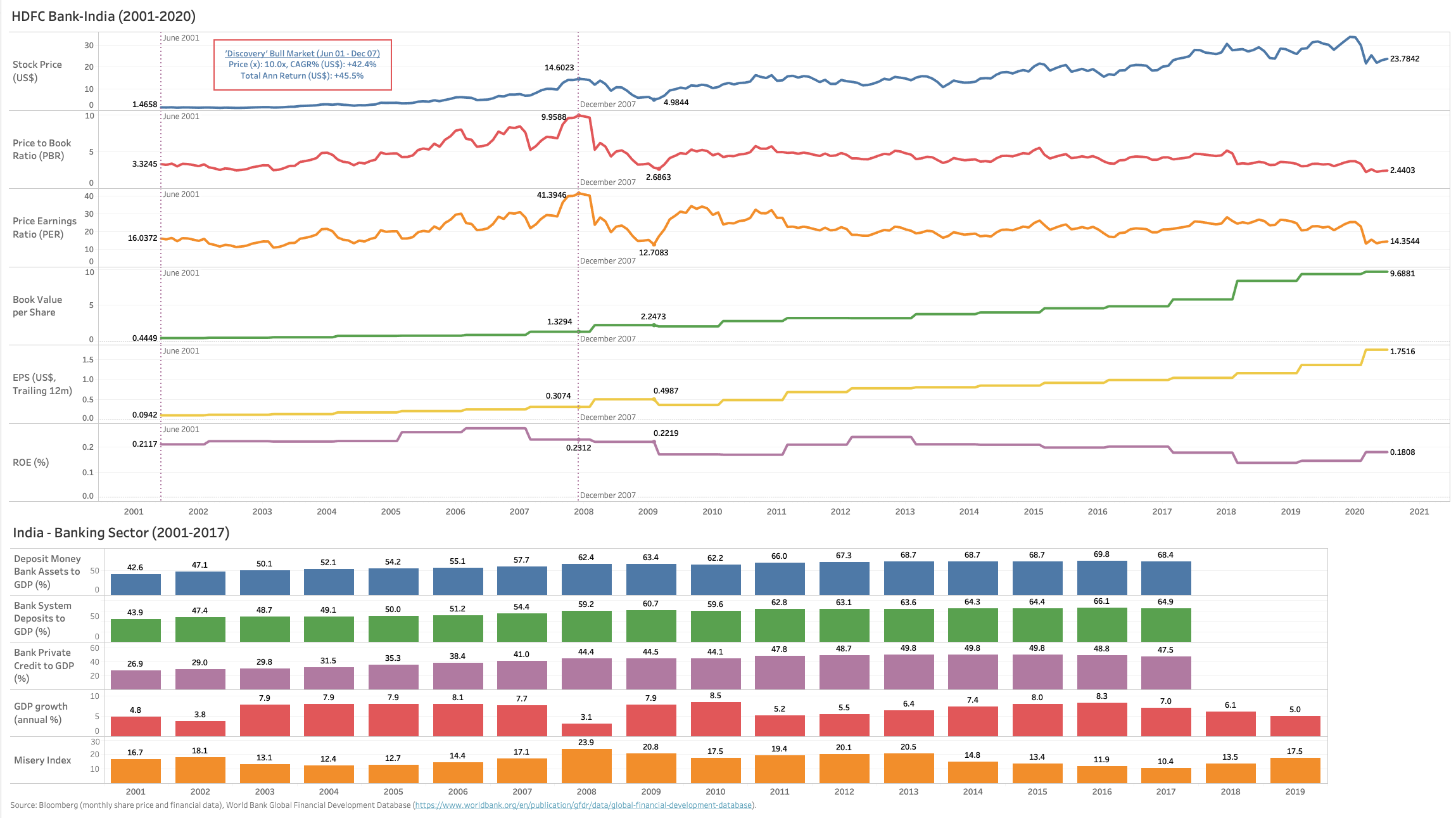

If we then look at the ‘trapped’ group relative to those countries which managed to ‘escape’ the resource trap in recent decades (e.g. Colombia, Peru, South Africa – green bars), the impact on non-resource growth, even in the 2013-18 period, was more subdued. This is due in large part to their diversification strategies where resource-rent intensity declined materially (in Colombia’s case it fell from 7% to 5.5%, Peru’s dropped from 15% to 9% and South Africa’s from above 11% to 6%). As a result, these countries far outperformed the ‘trapped’ group in terms of non-resource growth, volatility of growth in general and ultimately long run per capita income growth.

Finally, a note on the ‘Rich & Resource-Dependent’ group (turquoise bars) which consists of the GCC countries (Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, UAE, Oman), Chile and Russia (the latter straddles the ‘rich/resource-dependent’ and ‘trapped’ groups). Here, the paradox of plenty manifests itself in similar GDP growth volatility as their middle-income peers, but with meaningfully lower productivity growth rates, especially for those countries which adopted aggressive migrant labor import models (GCC) or primarily utilized higher factor inputs to drive overall growth. All of these rich countries, without exception, have large foreign savings, reserves or un-levered balance sheets that they are able to draw upon in order to finance counter-cyclical fiscal policies.

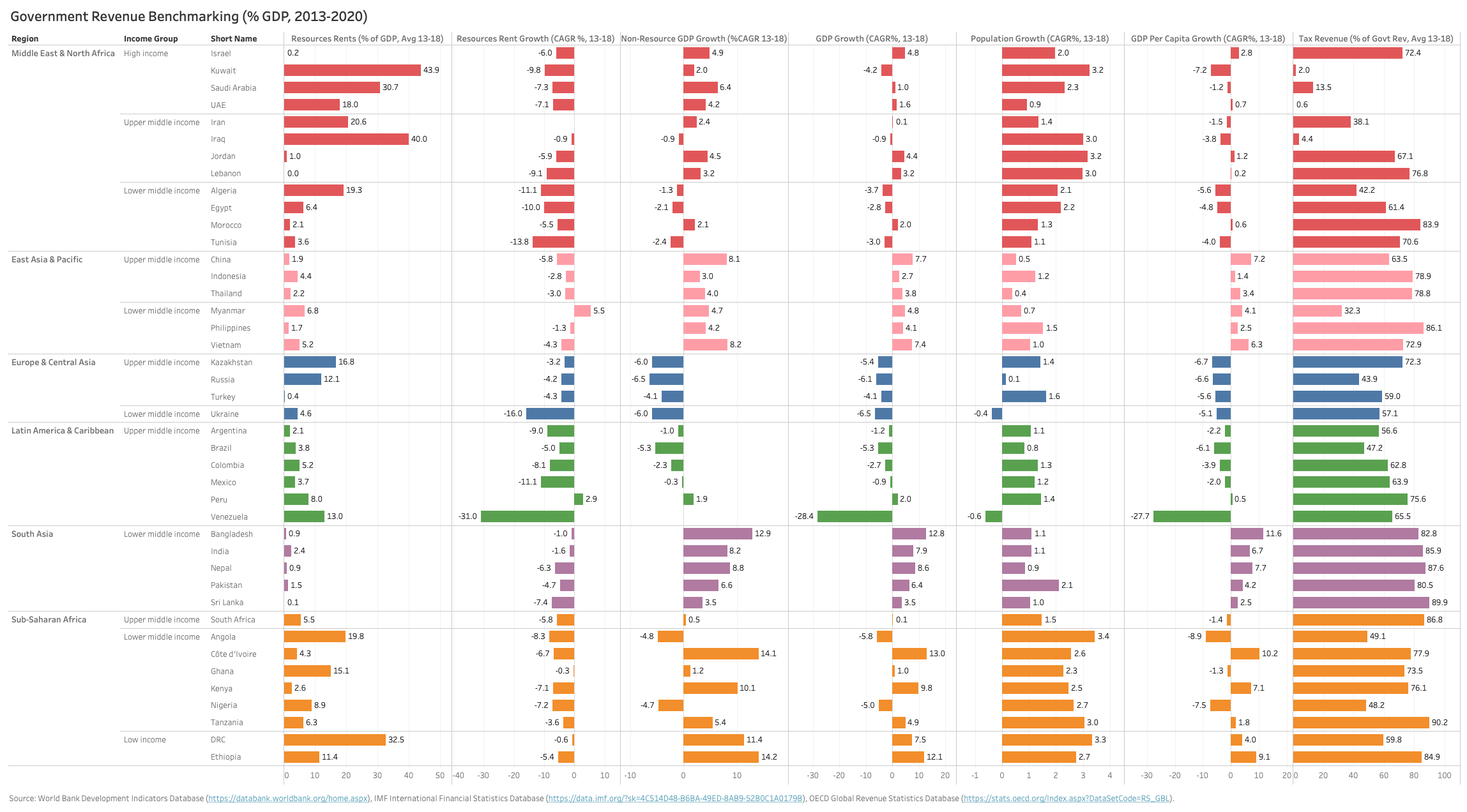

The high volatility of growth and the lack of diversification away from resources has in turn made the fiscal side much more dependent on fluctuating commodity prices for any resource-intensive country. General government budgets therefore are hostage to the commodity cycle (see Chart 19 below). As a result, essential government spending on social services also shrinks as deficit pressure mounts to curtail spending in a cyclical manner. Those countries that are more diversified are also able to fund counter-cyclical spending on social services via a broader tax revenue base. In this respect, Iraq is a major negative outlier since both tax revenues as a component of government revenue is so small and the external savings stock is very low.

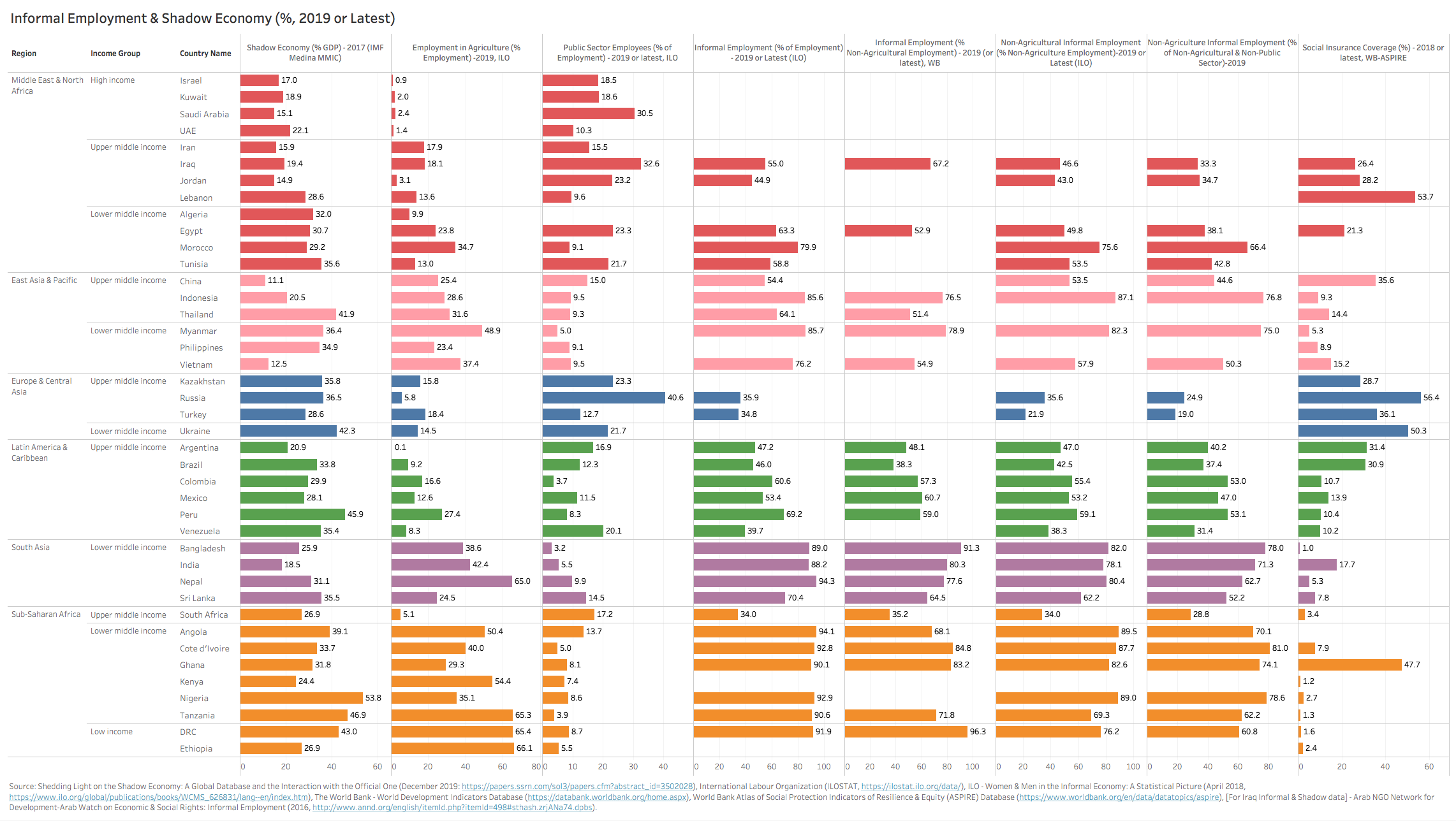

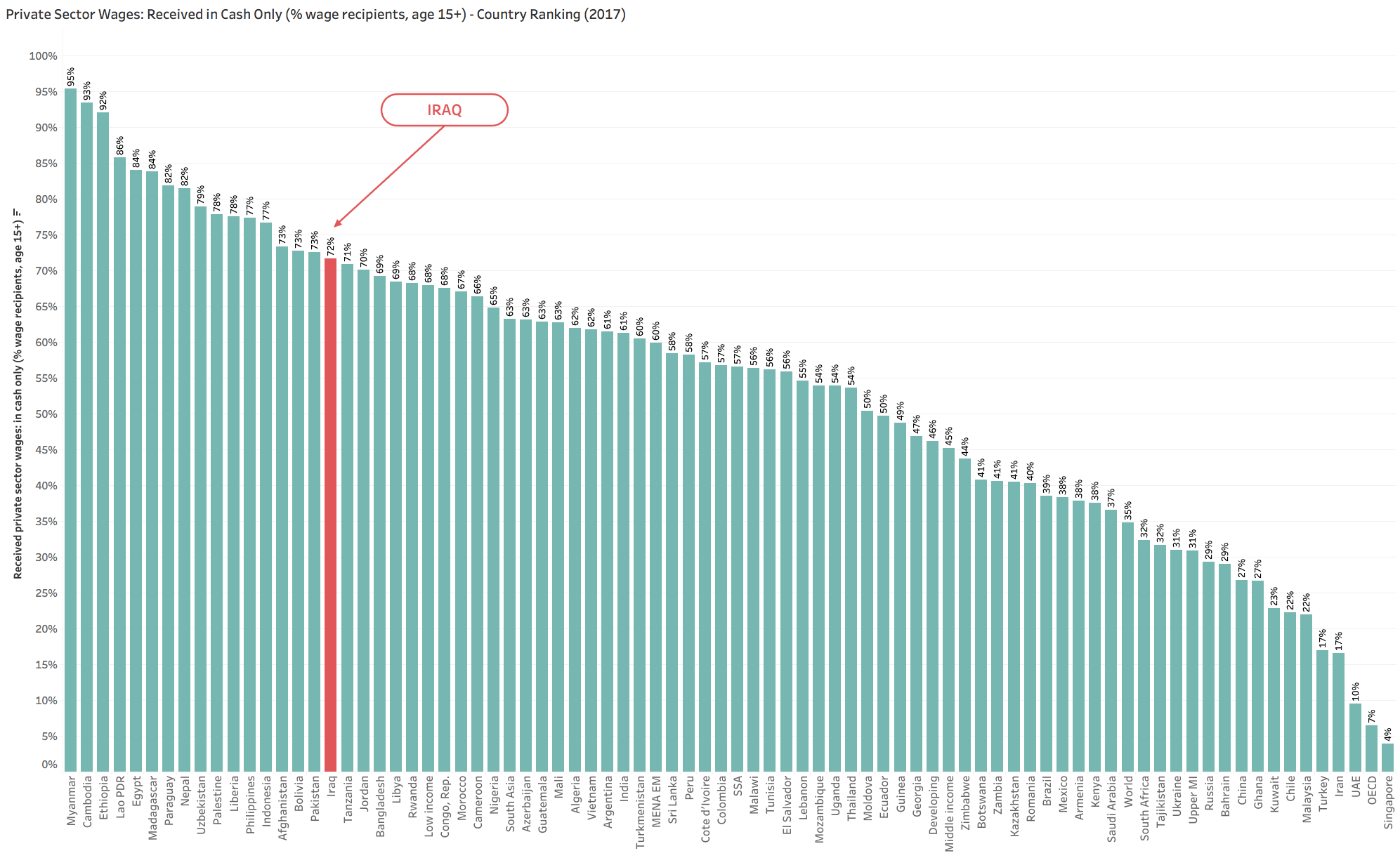

According to the IMF, Iraq’s tax revenue to GDP has averaged a paltry 1.4% (one of the lowest levels globally and in the same neighborhood albeit even lower than GCC states like Saudi and the UAE), while government revenues as a percent of GDP stood at 31% during this period, suggesting tax revenues as a share of total fiscal revenues averaged only 4.4%. This is corroborated by a structurally low level of non-oil government revenues to non-oil GDP which the IMF reports to be only 5.35% in 2019. This low level of non-oil government revenues has remained structurally low, rising from 2% in 2004 to 6.8% in 2017. Emerging market peer countries (across the spectrum of resource-intensive or diversified) have much larger tax revenue bases relative to their fiscal budgets (ranging from 32% in Myanmar to well above 80% for most of South Asia). Even the likes of Russia, Nigeria, Algeria and Iran are in the 40% neighborhood. Such a low tax base and low non-oil revenue base are suggestive of just how incredibly small the formal non-oil private sector really is in Iraq.

Chart 19: Government Revenue Benchmarking (2013-2020)

Iraq shares this extremely narrow tax base with only a handful of resource-rich peer countries, which are commonly referred to as rentier states (see Charts 20 & 21 below). Both charts look at resource intensity levels relative to each of the revenue metrics separately (government revenue and tax revenue). We chose this extra step to tease out Nigeria’s positioning, since even though tax/revenue is 48%, the relative share of overall revenue is very low vs. GDP (8.5% government revenue/GDP, 4% tax revenue/GDP). Apart from Nigeria, it is not at all surprising that the rest of the small club of countries that occupy this quadrant are rich GCC hydrocarbon exporters – all of which are Iraq’s neighbors in the Gulf region and most also join Iraq as longstanding members of the OPEC cartel, leading oil exporters and reserve owners.

Chart 20: Resource Rents & Tax Revenues (% GDP)

Chart 21: Government Revenues & Tax Revenues (% GDP)

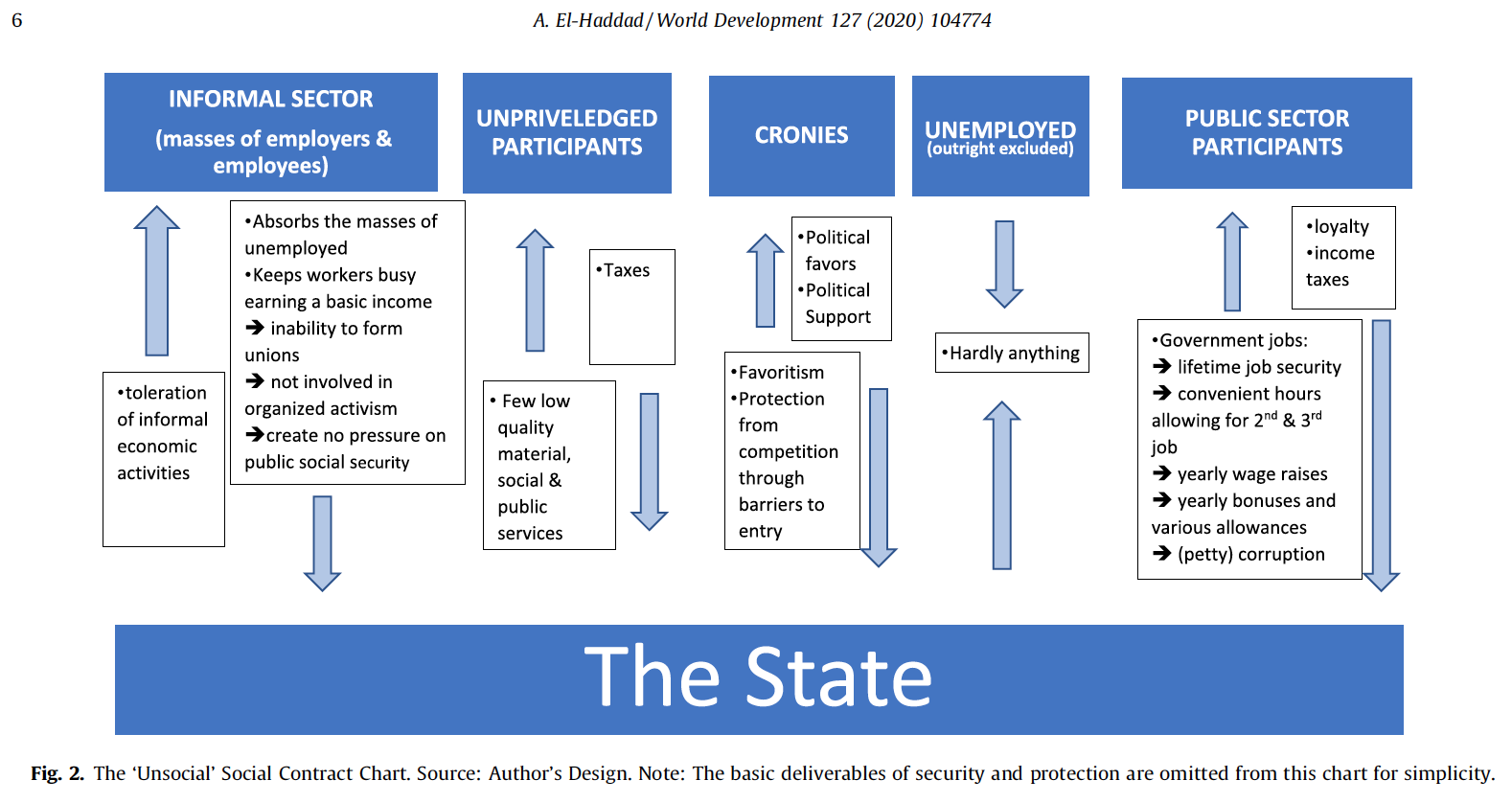

The ‘Unsocial Contract’

This small club of rentier economies also share a common social contract between governments and their citizens. They are predominantly autocratic governments that are not elected and therefore provide little in terms of ‘representation’. The GCC governments monopolize the resources of the state as well as how the rents from these resources are allocated and distributed, doling out social services as they deem fit, with little accountability, if any. As a result, the implicit agreement with their citizens is one where direct taxation is minimized or largely absent. As some of these rich countries start to diversify away from fossil fuels, this social contact starts to get challenged, particularly if the overall source of hydrocarbon revenue shrinks and the need for tax revenues rises as a result.

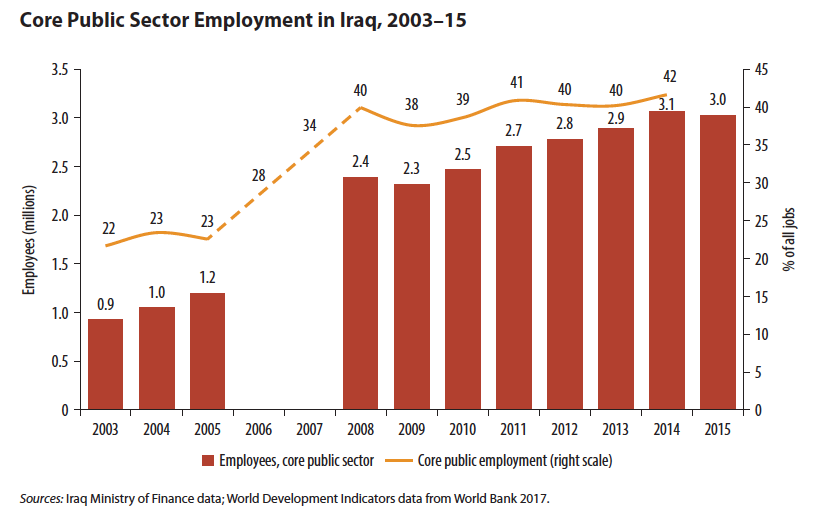

This ‘unsocial contract’ (see Chart 22 below from A. El-Haddad) manifests itself in Iraq in several ways: a) the public sector becomes the de-facto channel for ‘representation’ of Iraq’s oil wealth (that is for those with ample wasta or connections to actually get a government/militia job), b) oil-rents, which finance most public spending are vulnerable to volatile swings in oil prices, corruption/‘leakages’ (at worst) or inefficient public spending precisely because of weak institutions and lack of accountability, and c) government services are poor overall and extend only to a small portion of Iraqis that manage to benefit from this exclusive channel.

Chart 22: The ‘Unsocial Contract’

For the majority of countries globally, as the tax base rises, health and education expenditures also rise. Iraq joins several other rentier states, where an exclusionary system of ‘representation’ and a broken social contract hugely distort this relationship. A major dividend from diversification of the economy will be the gradual de-linking of state funding for social services from volatile oil revenues and a shrinking of the public sector in favor of a larger private sector that will help grow the tax base, with dividends to all Iraqi citizens in the form of better basic services.

Although Iraq currently shares some economic similarities to the aforementioned GCC states (in terms of resource-rent dependency, rentier development model, a broken social contract), the differences far outnumber these similarities and are of great interest to us at this particular juncture.

Iraq’s oil wealth, while significant in terms of reserve life and production potential (Iraq has the world’s 4thlargest reserves of oil, while boasting the highest reserve/production ratio of 83 years vs. top producers – see Charts A11-A12 in the Appendix) it cannot on its own sustainably generate a high living standard for its population. Like Nigeria, Russia, Iran and other large population countries that rely on oil as a major source of government revenue, Iraq is essentially forced to diversify in order to deliver a minimum acceptable standard of living for its citizens. This is particularly the case now with the developed world’s determined focus to wean itself off of fossil fuels in the next two decades in favor of renewable sources of energy. In an environment of structurally low oil prices, diversification becomes a necessity, not just an aspirational policy objective or the subject of an expensive McKinsey report.

Secondly, because of Iraq’s long history of decades of expensive war adventurism and the hundreds of billions of dollars in lost treasure lost, unlike most GCC countries and Russia, Iraq does not have a cushion of a large sovereign wealth fund or foreign reserves to fall back on. Like Nigeria, Iraq’s propensity and ability to save or borrow is low, due not only to the sheer size of the country’s population and the large state apparatus that is necessary to support it, but also due to the fact that the country’s infrastructure capacity is extremely weak and under-developed. Therefore, the anchor for both diversification and productive investment is dramatically stronger than for most middle- or high-income rentier states (this is a critical difference).

Third, Iraq’s hydrocarbon sector boasts a much higher share of investment/involvement from international oil companies (IOCs) than most (Nigeria is similar in this regard) which in turn have demanded a higher level of transparency and accountability in the oil & gas sector. As an example, this meant that in order to attract IOC investment early in Iraq’s production recovery phase, it needed to sign up to the EITI (Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative) charter. This not only has helped to attract foreign capital and know-how to the oil sector, it has also aligned Iraq’s oil revenue interests with those of the IOCs. This in turn gears Iraq’s resource exploitation model more towards that of a revenue-maximizer vs. a price- or market share-maximizer (as most GCC-OPEC members arguably are adopters of the latter two), thereby elevating the present value of oil revenues over the future value of reserves left in the ground and subject to the risk of becoming stranded assets. This once again calls into question Iraq’s membership in OPEC and its willingness to support prolonged production cutbacks, particularly since Iraq’s historical reserve exploitation has also been dramatically lower than the GCC or Iran because of its long history of instability.

Fourth, despite the dysfunctional and exclusionary manner which characterized the post-2003 Iraqi governance track record, the country has managed to build several strong and resilient state institutions, amongst them: a pluralistic electoral process, a trained and hardened federal military force, a functioning and independent central bank (since 2004 and reinforced in 2015) and the well managed quasi-independent state oil companies. Don’t get us wrong, there is obviously much more institution-building and strengthening that is needed. However, the checks and balances that are implicit in any inclusive sectarian governance model (if successful under a Khadhimi coalition or future governments) may in fact provide a much stronger and more resilient anchor for governance and reform vs. an autocratic ‘1-man’ (or ‘1-prince’) model.

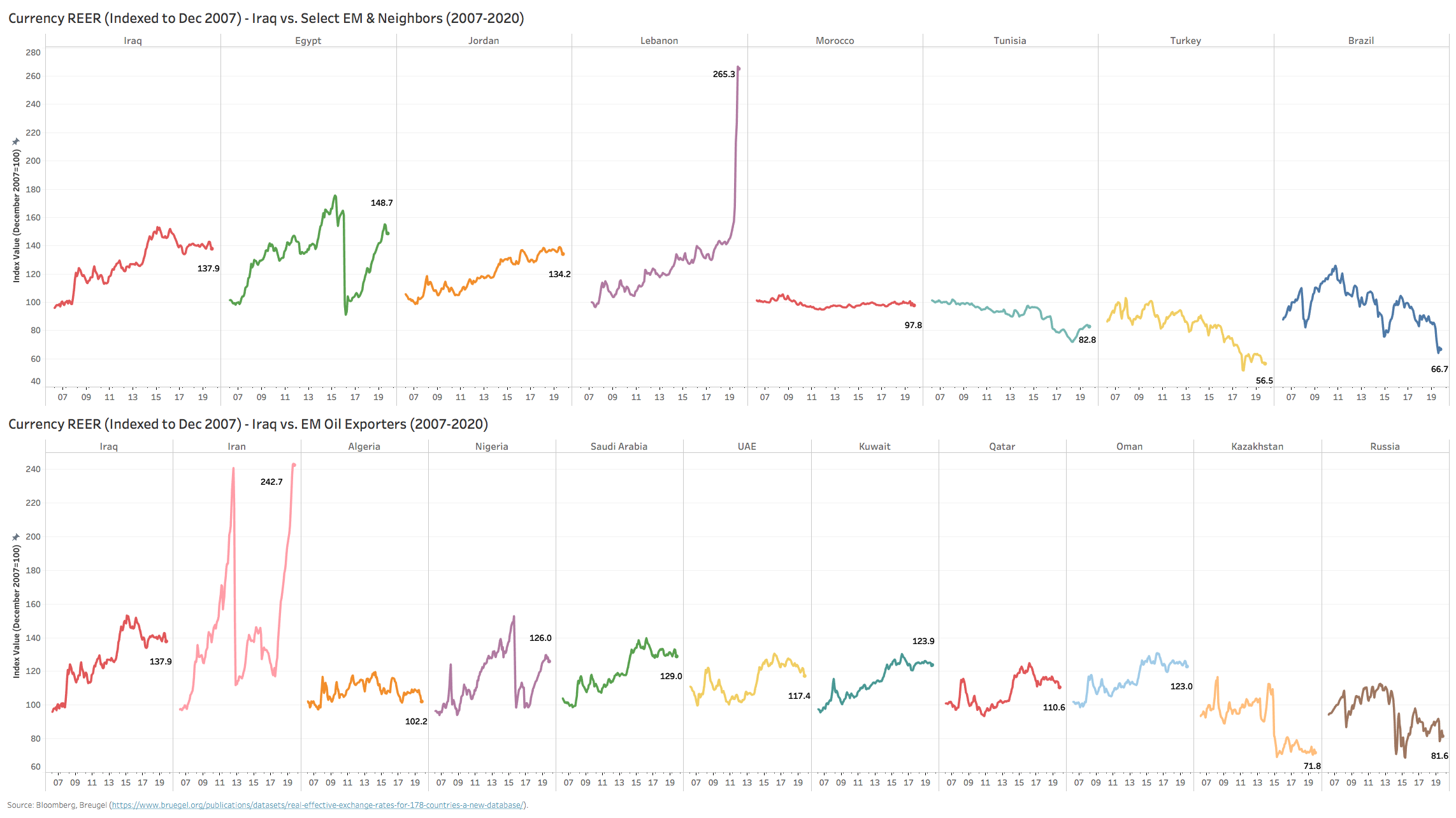

Fifth, unlike the GCC, we do not believe that the Iraqis necessarily view the US$ peg as sacrosanct. Unlike the longstanding GCC-US$-pegs, the Iraqi dinar was devalued substantially in the aftermath of the 2003 invasion but was re-pegged to the US dollar to arrest and contain very high inflation utilizing a dogmatic and narrow interpretation of monetary policy. Once Iraqi reserves are built back up to sufficient import coverage levels, the state banking system is restructured and liberalized and full capital account liberalization is complete, we see no reason why the IQD-US$ peg should be maintained. With the so called “dollar auction” system coming under intense scrutiny because of money laundering allegations, a planned privatization of Trade Bank of Iraq and with a more accelerated military disengagement by the US from Iraq, we expect the rationale for maintaining the peg to begin to weaken. A more competitive exchange rate for the dinar is much more aligned with both a revenue-maximizing oil export objective as well as a diversification-led development model. Having said this, and due to very low inflation of the past 5 years, the Iraqi dinar’s fair value does not seem to be highly dislocated relative to regional trading partners or other US$-pegged oil exporters (when viewed through a REER prism – see Chart A13 in the Appendix).

Finally, Iraq, and for that matter Nigeria, are not only much larger in population size, but both have chosen to adopt representative political systems of governance that at least in principle require accountability to their citizens. And yet, both countries have progressively acted more and more like rentier systems of late as demonstrated by their ever-shrinking tax revenue bases and rising resource intensity levels. As a result, their informal economies have ballooned, important social services like education and healthcare have deteriorated, crony capitalism has metastasized, and the public sector labor force has expanded to cushion the blow on unemployment. Sudden exogenous shocks to oil prices that are not cushioned by higher production have had a material impact on these countries’ ability to fund important social spending for their large, young and growing populations. Their ‘unsocial’ contracts have proven therefore to be much more vulnerable relative to their rich-resource peers.

Human Development

Most human development indicators for Iraq began to improve gradually during the post-2003 period according to the UN-HDR, with life expectancy gaining almost two full years to 70.5 from 68.3 and average years of schooling increasing from 5 to 7.3. Government spending on education and health was the main driver for this improvement as spending intensity ratios rebounded back to levels last seen only in the 1990s. This was obviously bolstered by a very strong oil revenue backdrop and occurred despite chronic budget under-execution (and leakages) by successive Iraqi governments for both capital budgets and recurrent operating budgets (some years were as low as 50% for the capital budget side per the World Bank).

Health and education spending (as a % of GDP) both rose to the 3%-4% levels by 2009 while per capita spending on both categories also snapped back but remained meaningfully below MENA and middle income averages (see Charts 23-26 below with expenditure trends for Iraq as well as benchmarking with emerging market peers). They were however well on their way to converging with the likes of Algeria and Kazakhstan on a per capita basis while even eclipsing many Arab peers like Morocco and Tunisia in health spending. In the case of education per capita, spending levels snapped back to above 1989 levels of $166/person, while health spending/capita grew from $53 in 2004 and eclipsed $150 by 2010, rising to over $200 by 2013. This sharp improvement occurred despite higher population growth during this past decade.

Chart 23: Iraq Fiscal Spending on Human Development vs. Military (1960-2018)

Chart 24: Fiscal Spending on Human Development vs. Military (% of GDP, 2013-2018)

Chart 25: Fiscal Spending on Human Development vs. Military (Per Capita, 2013-2018)

Chart 26: Iraq Government Spending by Ministry (2007-2015)

The 2015 oil price shock however derailed much of this momentum, with a sharp decline in rents per person, almost halving from $3,117 to $1,748 while military spending per person rose by over a third that year (from 3% to 5.3% of GDP and the highest level since 2003), mainly to shore up Iraq’s security forces in the aftermath of the ISIS insurgency that began the prior year. This in turn squeezed out spending on essential social services causing education expenditures to decline to below 1% by 2018 while preliminary budget reports indicated that health spending in 2018-2019 more than halved to below 2% of GDP. Even though Iraq spends only a fraction of what its GCC neighbors spend on arms (3%-4% of GDP vs. over 10% for Saudi or 6% for the UAE), the highly fixed nature of Iraq’s fiscal expenses (e.g. public sector wages which account for up to 50% of most year’s budgets) and its tiny tax base (averaged 1.4% of GDP in 13-18) in turn crowded out any spending on social services outside of the public sector. The dual shocks of the ISIS insurgency and the oil price drop brought Iraq’s ‘unsocial contract’ to a breaking point.

For Iraq, this acute neglect of the private sector and the proper infrastructure that enables it, has translated into yet another chapter of massive expansion of the oil-revenue-fueled state apparatus and yet another step taken away from diversification. This in turn created huge negative externalities, including: a) underinvestment in anything non-resource oriented, including Iraq’s security, basic infrastructure and social safety system, b) massive expansion in the public sector wage bill, c) the ballooning of the crony capitalist class that feeds off political favoritism while escaping competition, d) a further expansion of the informal sector which absorbs spillover job seekers and in turn perpetuates Iraq’s low tax revenue base and e) reinforcement of the poor environment for private investment (both domestic and foreign).

Let’s take several of these externalities that in our opinion represent key hurdles for sustainable reform and which themselves embody the core issues plaguing Iraq to illustrate their effects with some empirical data.

Underinvestment

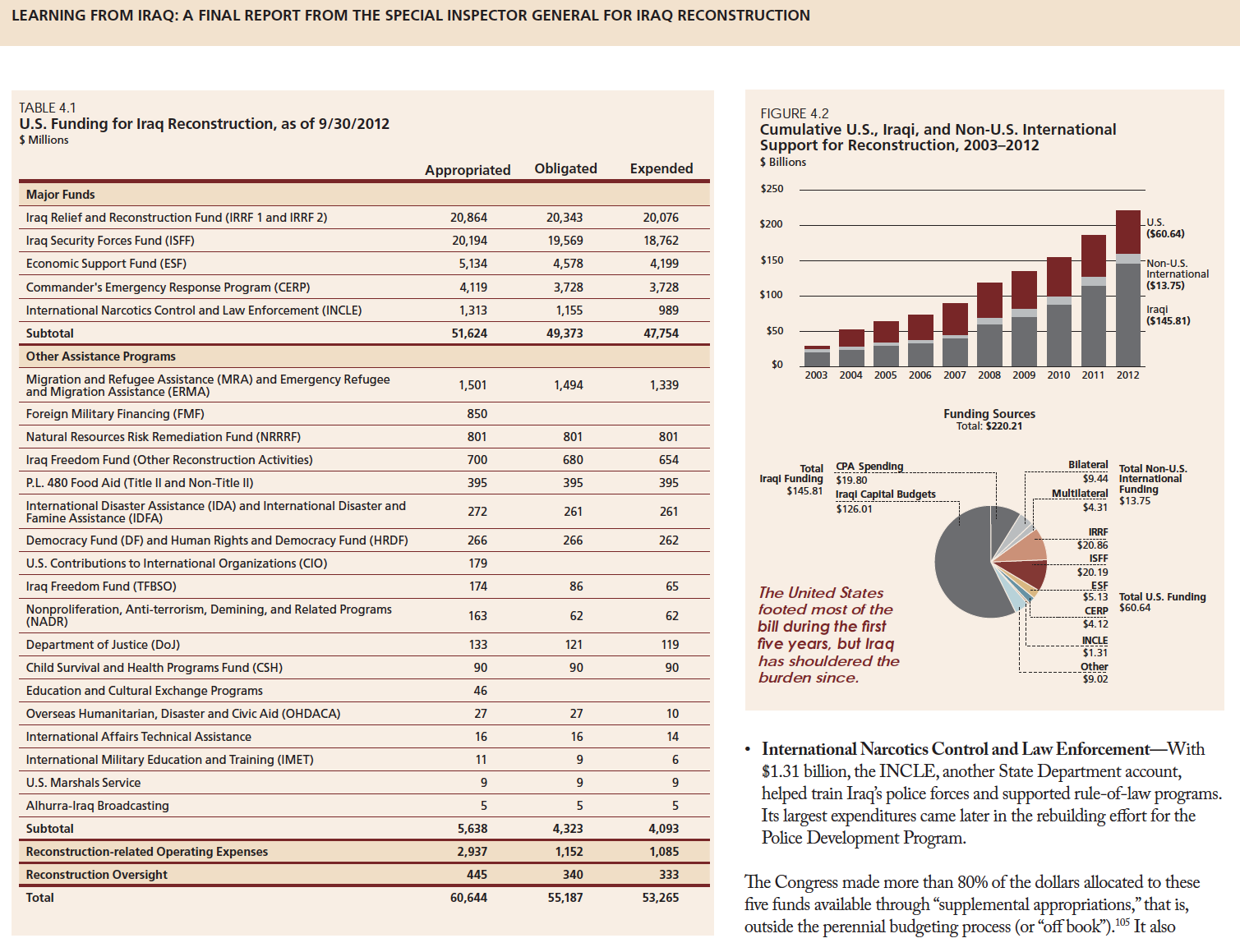

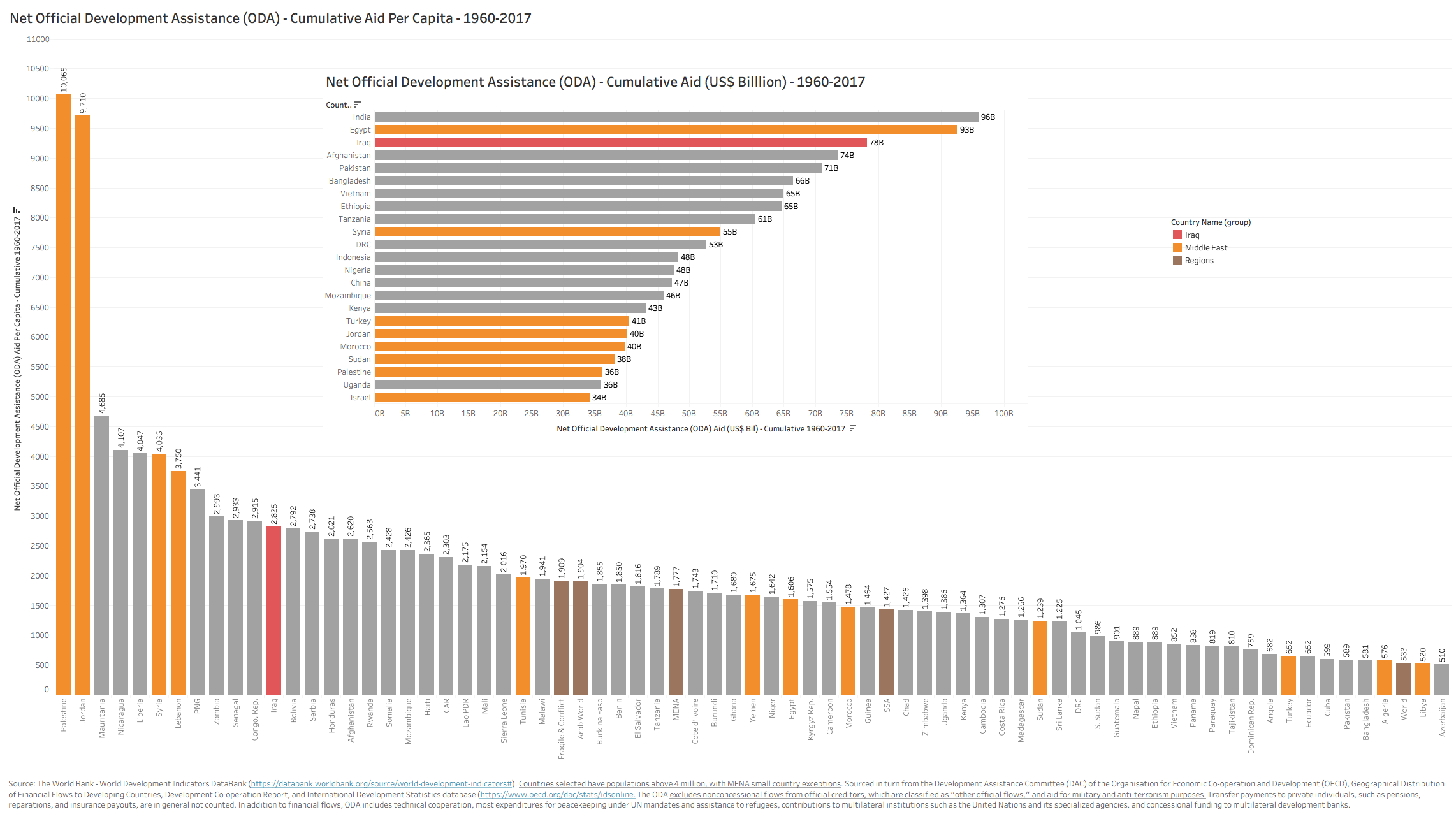

In the area of underinvestment, despite the billions of dollars spent on reconstruction by the US-led coalition and the Iraqi government in the years following the US-invasion (see Chart 27 below with a summary of 2003-2012 from the US Congressional Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction or SIGIR in 2013) there is very little to show for it in terms of non-oil productivity or infrastructure.

According to SIGIR, the US alone spent over $60 billion during this short period, with another $14 billion spent by the international community. On top of this, the Iraqi funding itself totaled close to $146 billion, with the majority coming from government budgets during this period (2003-12). Relative to the size of Iraq’s recovering economy, this deployment of capital was gargantuan (a total of $220 billion in outlays vs. a starting point GDP of $37 billion in 2004). Where did all this money end up and why has the impact thus far been muted?

Chart 27: US Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction (SIGIR) – Cumulative Spending (2003-2012)

The answer to this important question still evades us, despite decades-long donor-led forensic audits and investigations. The obvious conclusion is that a big portion of the money was ‘leaked’ to contractors and intermediaries, whether Iraqi or foreign. What is amply clear however is that there remains scant evidence that most of this capital was in fact deployed legitimately and productively. Even post 2012 in the ensuing years to date, assuming a similar run-rate of Iraqi government spending on reconstruction, this would imply total spending of approximately $250 billion on internal security, reconstruction and rehabilitation. So then why do most Iraqi cities still face chronic power shortages and deficits in everything from gasoline refining capacity to basic social services like garbage collection and water treatment?

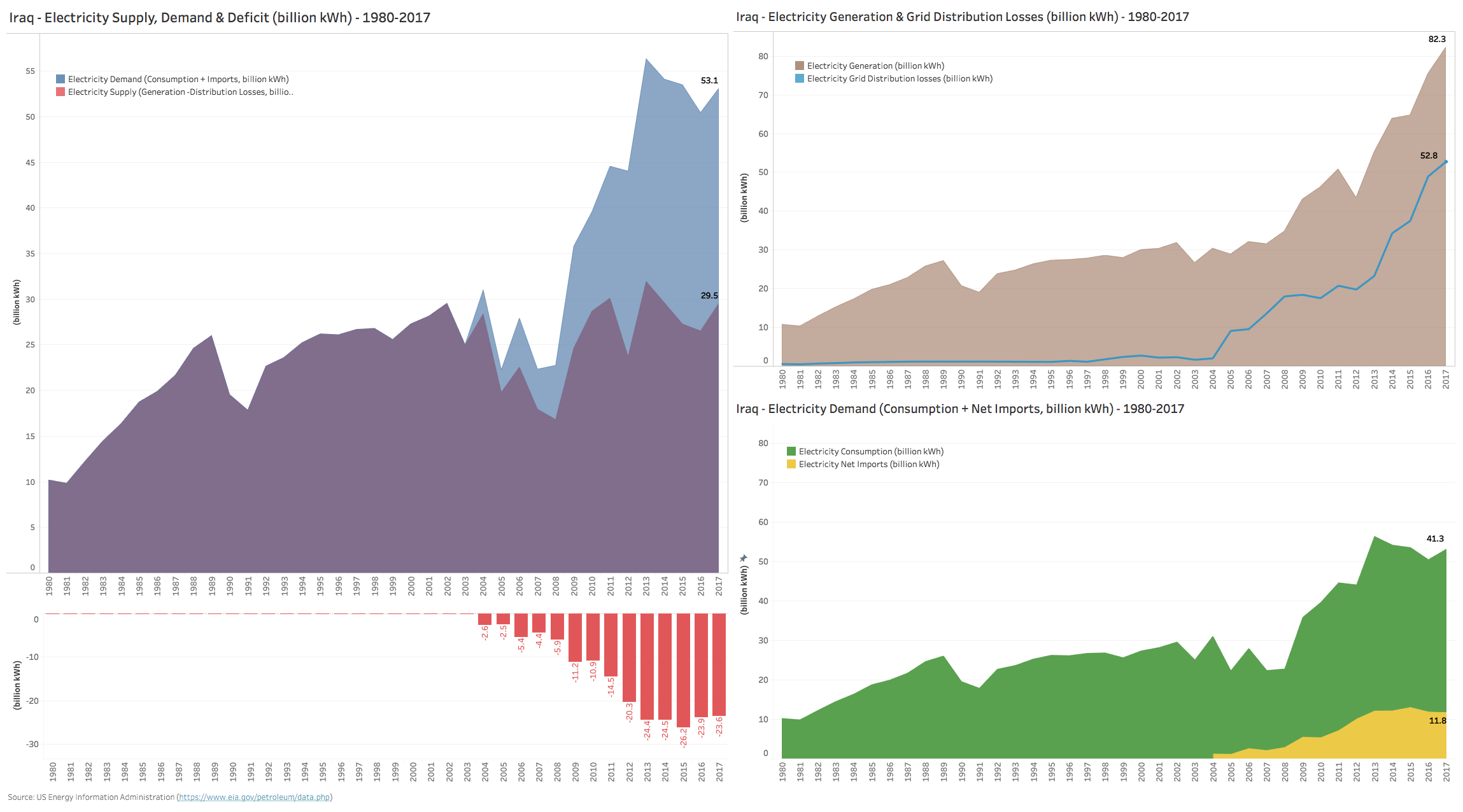

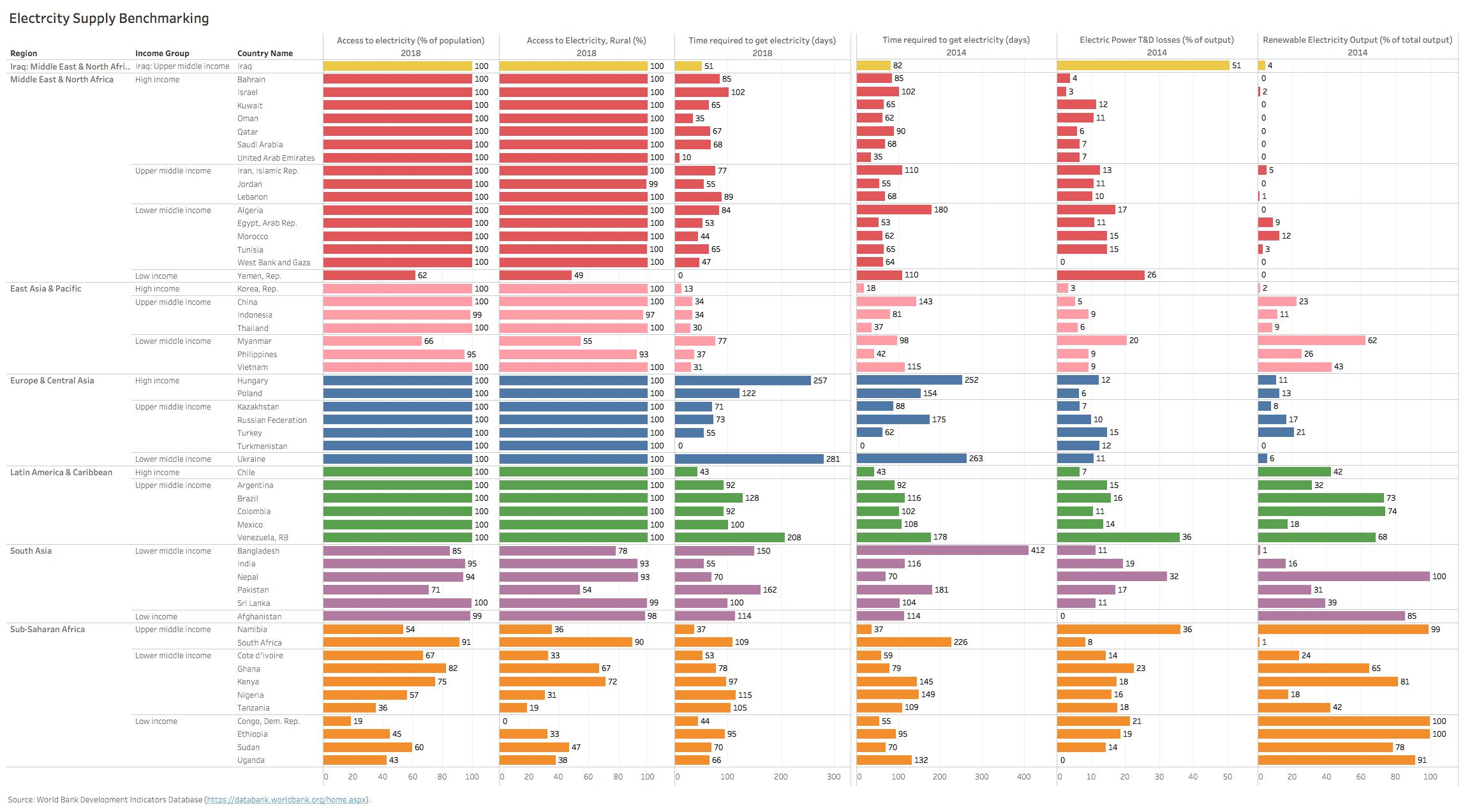

The chronic power sector deficit is a loud case in point and the reform challenge here is a really useful microcosm through which to view Iraq’s broader reform track record. Despite substantial investments in this sector since 2003 (almost $45 billion has been spent to 2015), most Iraqi cities still experience daily power cuts and rolling blackouts (some cities only get 9-12 hours of uninterrupted power; 15-hour blackouts on average), which have persistently inflamed public anger. While the generation side has had big capacity additions since 2003 (more than doubling to above 82 bkWh according to the EIA; Chart 28 below) almost two-thirds of this capacity is lost due to poor transmission and distribution networks, the highest loss percentage of any peer country in the developing world inclusive of Venezuela (see Chart 29 below with benchmarking).

Chart 28: Iraq’s Power Sector (1980-2017)

Chart 29: Electricity Supply Benchmarking (2014/2018)

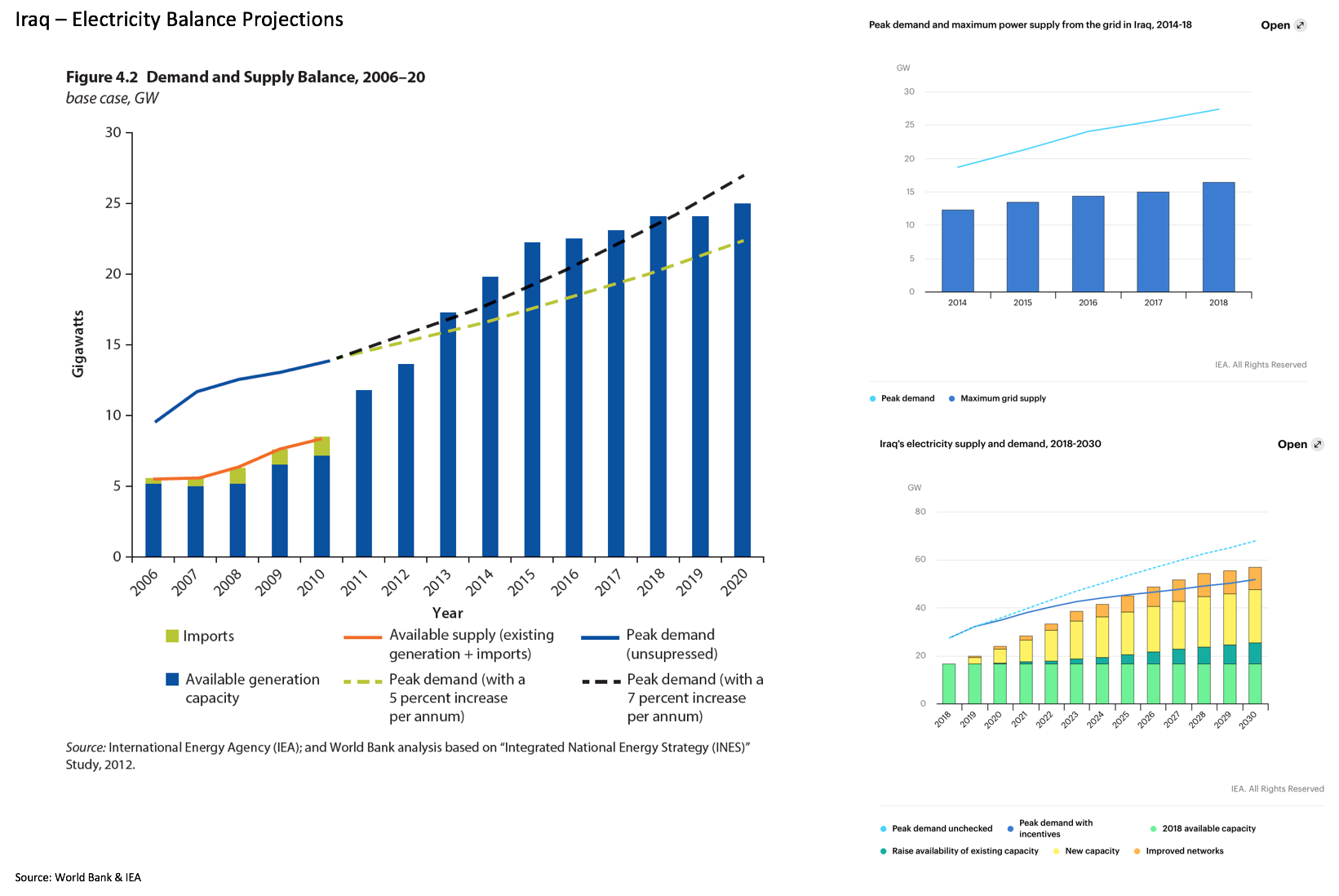

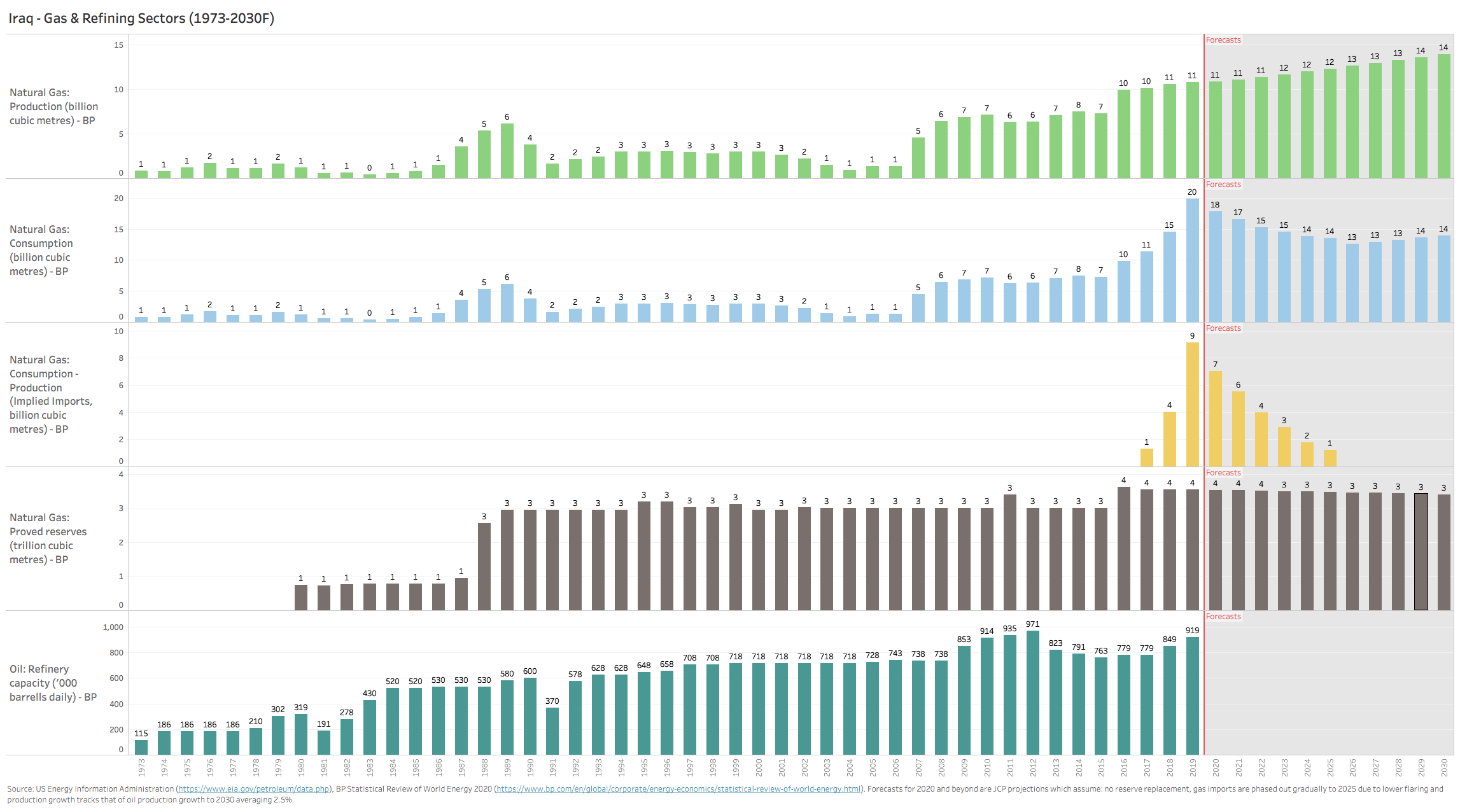

The 1990-91 war and the ISIS insurgency in 2014-17 took their toll on the national electricity grid, degrading or making almost one-fifth of the grid inoperable. Reports from the Iraq Energy Institute also indicate that less than a third of electricity supplied is ultimately paid for by customers (despite costing less than 1 US cent/kWh vs. an estimated cost to the government of 10 cents/kWh) exacerbating the commercial side of maintaining the grid and upgrading the network. According to the IMF, in 2018 these power sector subsidies alone accounted for almost 10% of total government expenditures (yet another stubborn fixed cost). To plug the large and growing power deficit (23.6 bkWh in 2017 and representing 44% of overall demand) Iraq has been forced to import expensive electricity from Iran and Turkey (11.8 bkWh or 22% of demand). In the meantime, Iraq is one of only a handful of countries still flaring associated gas (16 bcm was flared in 2018; Iraq is endowed with the world’s 12th largest gas reserves but 70% of it is associated gas). The lack of investment in gas pipelines prevents Iraq from monetizing this asset at the wellhead instead of flaring it, which if done could save over $5 billion annually by making imports redundant (according to a recent report from Georgetown University). Both the IEA and World Bank expect Iraq’s electricity demand to double by 2030 (Chart 30 below), just tracking demographic growth and a normalized consumption intensity, entailing over $90 billion in investments.

Chart 30: Iraq’s Electricity Demand & Supply Balance Projections (2006-to 2020/30)

Reform in this area is of obviously critical. Not only is access to power a basic prerequisite for a minimum level of human productivity and living standards, it is the primary enabler of industrialization and commercial activity. Despite its elevated importance, reforms here seem to have hit roadblocks that are all too familiar – a bloated and rigid SOE sector which includes most of the generation entities and the national grid, poor investment execution of past budgets (both ‘leakages’ and bureaucracy) and a reluctance to privatize or deregulate, thereby avoiding to embrace a market-based tariff framework which would reduce commercial losses and incentivize more efficient consumption.

Reforms & Corruption

While the broader reform report card for Iraq is a subject of intense scrutiny and analysis, it is important to step back and look at the attribution for reform performance and the trends underlying these attributes.

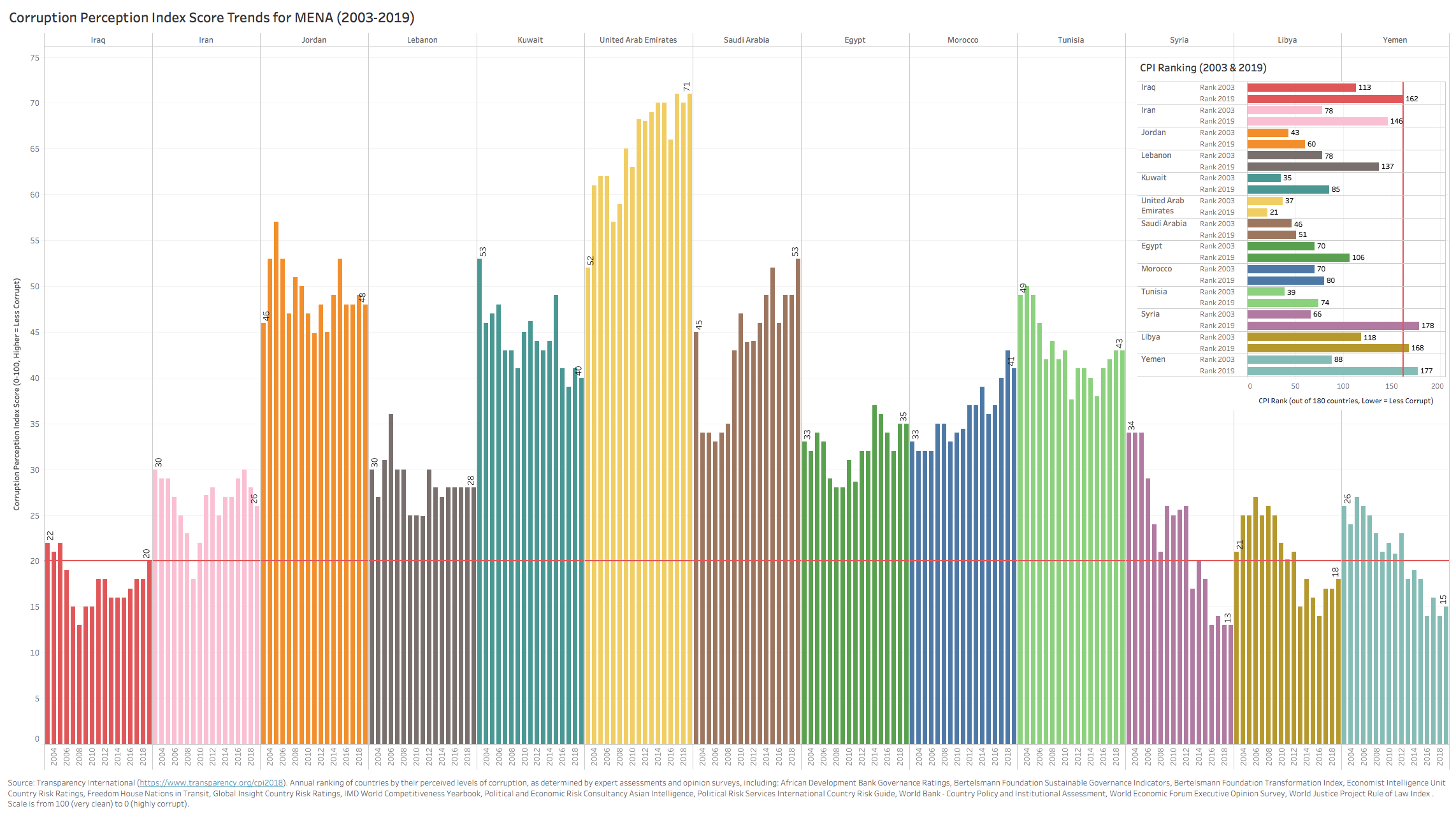

Lets tackle corruption first. Talk to anyone about corruption in Iraq, and you will likely get a mouthful of anecdotes, data and statistics that support Iraq’s extremely poor ranking globally in terms of its corruption perception index (‘CPI’) score (Chart 31 below with data from Transparency International). In fact, Iraq’s ranking has deteriorated markedly since 2003, falling from 113th ranked to 162nd by 2019. But this poor ranking masks the improvement in Iraq’s score which bottomed in 2008 and has slowly improved since then. Despite this, Iraq’s score remains in the bottom decile of countries worldwide, while ranking third worst within MENA and ahead of only Libya, Yemen and Syria.

Endemic corruption obviously remains a chronic and important impediment for any kind of reform or sustainable growth, but we believe that corruption is more of a symptom of poor and non-inclusive governance and weak institutions than it is the cause.

A recent superbly written NYT article ‘Inside the Iraqi Kleptocracy’, paints a detailed and very vivid expose’ of corruption in Iraq, tracing many of these symptoms back to what the author deems to be their root origin – primarily US complicity via political interference. The examples he gives are too numerous to list. Here are a few in summary: 1) US complicity in clearing Iraqi oil sales via the Federal Reserve, while reinforcing strict financial sanctions against Iran & Syria – effectively incentivizing illicit flows and money laundering through the Iraqi banking system, 2) US complicity in supporting oligarchic tendencies, crony capitalists & powerful militias tied to ruling governments that are now shaking down entire provincial governments, 3) the ‘ghost soldier’ kickback schemes in the military which laid the ground for an embarrassing retreat by an under-resourced army when ISIS emerged on the scene in parts of the country, 4) the ‘unwritten’ manner in which ministry appointments are made to purely sectarian-factional interests (again with direct US complicity) and 5) how the US-designed and supported FX auction system was effectively set up and used to promote fraudulent transactions just to benefit a small group of arbitraging middle-men. Robert Worth, the article’s author, describes the corruption brought about by the FX auctions as follows:

“It is impossible to say exactly how many billions have been stolen through exchange-rate arbitrage, but several former bankers and Iraqi officials told me that this kind of fraud accounts for most of the ostensible imports financed by the dollar auction since around 2008. My own estimate, based on figures from the central bank’s website and information from Iraqi bankers and finance officials, is about $20 billion, all of it stolen from the Iraqi people. The businessmen running the scheme are virtually printing their own money, because their costs — paying for fake invoices and bribing bank and government officials — are low. Some of the banks posting enormous profits from the auction are little more than fronts, with dilapidated branch offices and scarcely any employees. One bank bought $4 billion in dollars on the auction, I was told by a member of Parliament who has investigated corruption cases, a total that would correspond to a profit of $200 million. “We checked on this bank,” the lawmaker said. “It has one room, one computer and some guards.”

“The damage caused by the auction fraud was not just about illicit profits. As Iraq’s commercial banks transformed into instruments for arbitrage, ordinary businesses were left without access to the loans they needed to grow. Some legitimate importers, unable to get dollars from the auction, were forced to use foreign banks instead. It is hard to know how much harm this did to the economy, but all the analysts I spoke to said it has been devastating, starving the country’s private sector and making Iraq even more dependent on its oil proceeds, which have been cut in half in recent months.”

It’s a fantastic article and one that is a must read for anyone that is concerned about Iraq’s future. However, the article while thorough in identifying all the varied forms and channels of modern-day corruption in the country’s ‘self-sustaining system’ of kleptocracy, it comes up short on diagnosis and possible remedies. Having covered early stage developing countries for decades, we must admit that Iraq doesn’t seem to be materially different than most developing countries that face endemic corruption in their societies (definitely the majority of developing nations in our opinion). The biggest difference between Iraq and say Bangladesh, India or Colombia are: a) the alignment of interests and a sense of inclusion between the country’s various stakeholders, b) the strength of the state’s institutions (not just the judiciary, but also legislature, education system, police, the central bank and others), and c) the sanctity and enforcement of the rule of law. Iraq has built the foundations for all of these key pillars; they just need to be reinforced and strengthened by an empowered and courageous leadership. We strongly disagree with the author’s suggestion that only an autocratic strong man like Singapore’s Lee Kwan Yew can be an effective antidote for such a disease, no matter how entrenched or spread out it has become.

On the remedy side of things, it is also important to acknowledge that for many of the laundry list of symptoms of corruption, there are as many effective and pragmatic reform and regulatory options that are by no means exclusively available to autocrats or strongmen. Take for example the corrupt and misguided auction system described above. An effective regulator at the CBI and a full liberalization of the banking system would provide a level playing field and introduce intense competition for FX dealing which would in turn eliminate the artificial arbitrage spreads for sham outfits. Iraq is not the first country, nor will it be the last, to deal head on with both an entrenched culture and symptoms of corruption. Success is not a binary function nor can it happen overnight. Leadership that understands this and is willing to undertake these remedies incrementally is what has been missing so far.

Chart 31: Corruption Perception Index Score Trends – MENA (2003-2019)